The alarming surge in MPOX cases across the world is a matter of great concern. Diseases are no longer endemic. With globalisation and increased travel, diseases spread globally with devastating consequences. Yet, there is no co-ordinated effort to fight potential global threats. There is an inequitable distribution of public health resources to fight diseases. Ergo, people in poorer countries — developing nations — are primarily at risk, with limited access to vaccinations, medicines and information.

Point in case: the World Health Organisation’s declaration of Monkeypox as a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’—the ‘highest alert level for events that constitute a public health risk to other countries and requires a coordinated international response.’

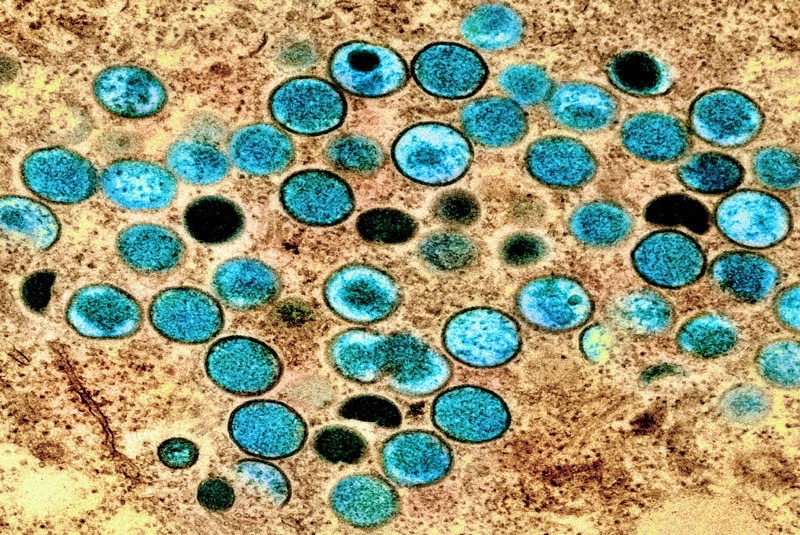

Monkeypox, a zoonotic virus belonging to the species of pox viruses such as smallpox and cowpox, was first discovered in 1958 among captive monkeys. In 1970, scientists identified the first human case, but the West largely ignored it as it was considered an ‘uncommon infection’ endemic to African countries.

Today, there is an ‘alarming surge’ in the number of monkeypox cases—particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, Ghana, Nigeria, Liberia, Cameroon, South Africa, Kenya and Uganda. Though the infection is sweeping throughout Africa, it has spread (and is continuing to spread) across the world at an alarming rate. The WHO committee considered it an “extraordinary event, which constitutes a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease, and potentially requires a coordinated international response,” and promptly declared it a ‘Public Health Emergency of Global Concern.’

The Monkeypox virus has two strains: Clade II and Clade I. Now, both strains have mutated into sub-clads. Clade II is less dangerous, with a case fatality rate of 0.1 per cent. However, Clade I is a virulent strain; it has a fatality rate of 3 to 4 per cent (meaning three or four people die in a hundred infected cases). In comparison, Covid had a fatality rate of 1.2 per cent. The genetic changes make the viruses spread and mutate quickly. The new strain has already spread rapidly to sixteen countries; six new countries were affected in ten days. It is likely to affect more countries.

The virus changes and mutates as it passes through lots of people; the more people it passes through, the more opportunity it has to change and become more virulent and transmissible. That means it is particularly problematic for countries and places with a high concentration of people—Africa and South Asia will be particularly affected.

According to the WHO, the Clade I strain of the Monkeypox virus spreads through close contact between people. ‘Close contact includes being face-to-face (such as talking or breathing close to one another, which can generate droplets or short-range aerosols); skin-to-skin (such as touching or vaginal/anal sex); mouth-to-mouth (such as kissing); or mouth-to-skin contact (such as oral sex or kissing the skin).’ Also, the monkeypox virus ‘persists on clothing, bedding, towels, objects, electronics and surfaces that a person with mpox has touched.’

The Monkeypox virus, particularly the Clad Ib strain, has a longer incubation period—from 5 to 21 days; an infected person can go undetected even during the screening process, travel to another country and transmit the disease. Infected people have vague symptoms—swollen glands, fever, and feeling a bit run down. Women and children are disproportionately affected by skin-to-skin contact. Children, for instance, can get infected as they touch objects and each other while playing games.

The shortage of vaccinations is a major problem. There are limited stockpiles of MPOX vaccines. The United States and Europe have developed and stockpiled vaccines, mostly in preparation for a potential bio-weapon attack using a pox virus. However, only 200,000 doses are available to African countries compared to a demand of at least 10 million. Furthermore, it is challenging to manufacture vaccines quickly. Consequently, the WHO called for vaccine candidates to be approved and distributed quickly.

Complacency in tacking the Monkeypox virus would be misguided. Ergo, it is essential to prepare for an eventuality on a war footing. The government of India must set up screening facilities throughout the country—in every district—to identify and contain the possible spread of infection. Separate facilities—sterile zones—must be established to treat infected people.

The government of India must also quickly identify, manufacture and stockpile vaccines on an immediate basis. It must work with private sector players to ensure that the vaccine doses are stockpiled and stored for safe use. Moreover, the Government must ensure that public messaging is clear, consistent, and accurate; adequate measures must be taken to contain the spread of misinformation—particularly socially divisive, communal rumour-mongering on social media.

India must also consider this an opportunity to help other African countries—particularly with aid for medical research and the development of vaccines. The government of India must establish a collaborative research consortium to tap into the expertise of African researchers in understanding the spread of the monkeypox virus.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]