Ants, the tiny marvels of the insect world, are a testament to nature’s extraordinary complexity and resilience. Despite being small, ants wield Herculean capabilities, such as their ability to lift to 20 times their weight.

With millions of years of history, ants have evolved into a highly organised and successful social species. In our daily lives, we encounter colonies of ants tirelessly working in concert, much like humans in their daily tasks.

From a taxonomic perspective, ants belong to the Animalia kingdom, Arthropoda phylum, Hexapoda subphylum, Insecta class, Hymenoptera order, Apocrita suborder, and Formicidae family.

Apart from this, there is one more classification among ants. Within ant colonies, there exists a complex division of labour, categorising ants into distinct roles. Their society comprises the ‘Queen Ant,’ which is the reproductive female in the colony. Her primary function is to lay eggs to ensure the survival and growth of the colony. Queen ants are usually the largest ants in the colony and may live for several years.

The second class is the ‘Worker Ants,’ sterile females responsible for various tasks essential for colony survival. The division of labour among worker ants is often based on their age and physical development.

The worker ants include: ‘foragers’ who search for food sources, collect food, and transport it back to the nest; ‘nurses’ who care for the queen’s eggs, larvae, and pupae, ensuring their well-being and development; and ‘soldiers’ who are responsible for defending the colony against potential threats, such as predators or intruders.

The last category is the ‘Male or Drone Ants,’ whose sole purpose is to mate with the queen. They typically have wings and shorter lifespans, as they die shortly after mating.

Ant colonies thrive through meticulous organisation, where nests become thriving hubs of life, exhibiting an orchestration of temperature and humidity. Communication transpires through the nuanced language of chemical signals, namely, pheromones, a dialogue uniting their purpose from foraging to nest defence.

Although ants often go unnoticed in our daily lives, their impact on humans is significant. These creatures have been a source of fascination, frequently depicted as mimicking human actions.

Anthropomorphism, the attribution of human characteristics or emotions to non-human entities, is often employed in literature and film. In multiple stories and movies, ants have been used as a metaphor or central theme to explore human behaviour, emotions, and societal dynamics.

This is done by the technique of humanising ants. That is, by imbuing ants with human traits and emotions, authors and filmmakers create a bridge of empathy between the audience and the tiny insect characters.

It allows audiences to relate to ants on a deeper level despite their vast differences in size, biology, and behaviour. It underscores the idea that emotions, struggles, and relationships mirror human experiences, even in the microcosmic world of ants.

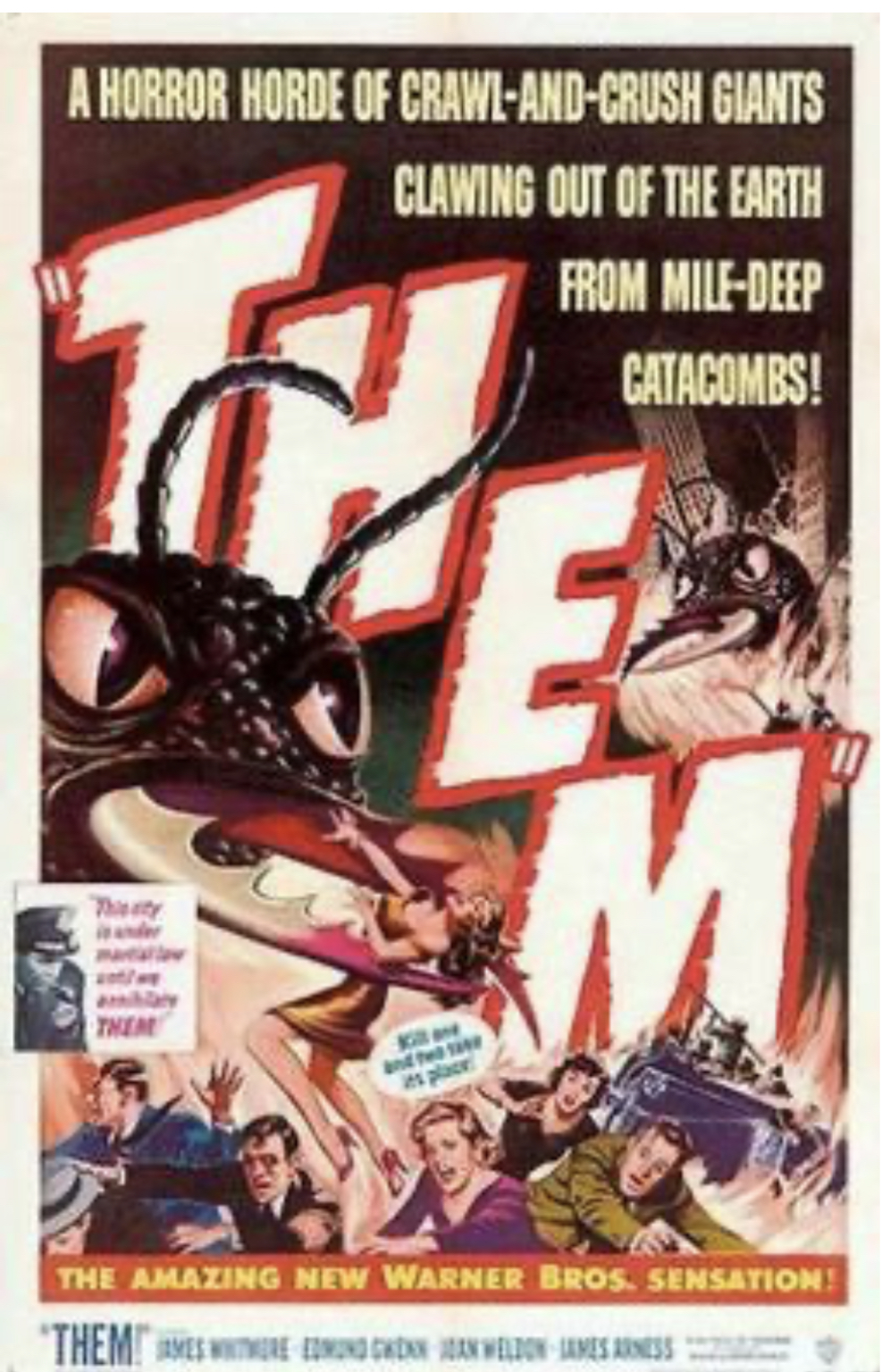

“Them!” is one such classic science fiction film released in 1954 and was directed by Gordon Douglas. It tells the story of an American desert plagued by giant irradiated ants mutated by an atomic bomb. A team of scientists and the military join forces to investigate and combat this seemingly insurmountable threat.

‘Them!’ effectively taps into the Cold War fears of nuclear bombing and its potential consequences, and it reflects the anxieties of the time.

When ants are anthropomorphised, their societies often serve as a mirror for human society. The hierarchical structures, division of labour, and conflicts within ant colonies can symbolise aspects of human civilisation, from social hierarchies to political struggles. This approach allows authors and filmmakers to explore human societal dynamics and behaviours indirectly through the lens of ants.

‘The Naked Jungle’ is another classic adventure film directed by Byron Haskin, based on a story by Carl Stephenson. The film, set in the early twentieth century in the South American jungle, follows a cocoa plantation owner, Christopher Leiningen, who lives a solitary life in his remote jungle estate.

Leiningen’s life takes a dramatic turn when he marries a mail-order bride and brings her to the plantation. Soon, the couple faces a dire threat when a massive army ant swarm begins its annual migration, consuming everything in its path. The film explores themes of survival, determination, and the clash between human civilisation and the relentless forces of nature embodied by the voracious army ants.

In some cases, anthropomorphism is used for a more lighthearted and whimsical exploration of ants’ lives, emphasising their tiny world’s intricacies. This approach may create a sense of wonder and amusement, reminding the audience of the joy of seeing familiar human traits in the insect world.

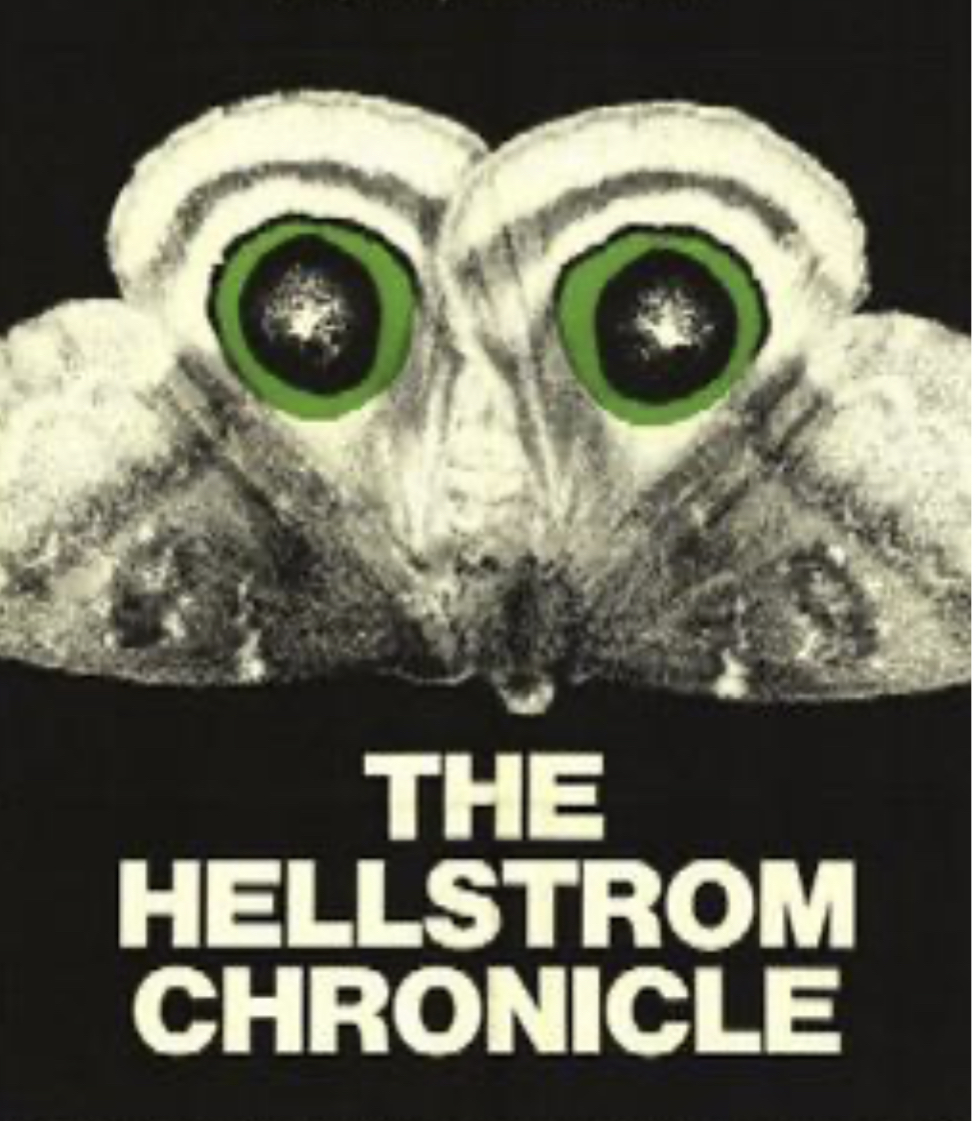

‘The Hellstrom Chronicle’ is a fascinating documentary-style film directed by Walon Green and Ed Spiegel. The film portrays the work of Dr. Nils Hellstrom, a fictional scientist who explores the world of insects and their potential impact on the future of humanity.

Throughout the documentary, Dr. Hellstrom discusses and observes various insects, including ants, to emphasise their remarkable evolutionary adaptations and success as a species. He suggests that insects may outlast humans in the evolutionary struggle and could potentially dominate the world in the future. This documentary reflects on the balance of power in the natural world and the potential consequences of human actions on the environment.

Anthropomorphising ants enables storytellers to evoke a wide range of emotions in the audience. While ants may symbolise resilience and determination, they can also evoke pity, admiration, and fear. This emotional complexity adds depth to the narrative and prompts viewers or readers to reflect on their emotional responses to the story.

‘Phase IV’ is a science fiction film directed by Saul Bass. The film is set in a remote desert research facility where two scientists, James and Ernest, study ant behaviour. They observe that the local ant population is behaving unusually and collaboratively, rapidly advancing their intelligence. As the ants become more intelligent and organised, they pose a significant threat to the humans in the area.

The scientists, joined by a local woman named Kendra, find themselves in a desperate battle for survival against the highly evolved ant colony. The film delves into themes of evolution, human intervention in nature, and the potential consequences of scientific experimentation.

In narratives where isolation and obsession play a significant role, the anthropomorphism of ants may represent a coping mechanism for the human characters. The fixation on the ants allows characters to project their emotions and desires onto the insects, helping them maintain a semblance of connection and sanity. This illustrates how the human mind can use anthropomorphism to make sense of and find comfort in extreme isolation.

In the movie “Oldboy” directed by Park Chan-wook, for example, a famous scene involves the protagonist seeing ants, which can serve as a commentary on the universal human need for connection and meaning, regardless of the circumstances. This scene is often interpreted as an analogy for human emotions and behaviour.

In one scene, a girl asks him, ‘The ants, do you still see them? Do you still feel that way? Yeah, if you are alone, you see ants. People I have met who are very lonely have all hallucinated about ants. Ants move around in groups, you know. So I suppose very lonely people keep thinking of ants.’

This scene is a powerful metaphor for the dehumanising and isolating effects of long-term imprisonment. Oh Dae-su’s fixation on the ants is a commentary on the human capacity to find meaning and connection even in the most dire and isolated circumstances. It also highlights how isolation can distort one’s perception of the world, leading to an intense focus on the most minor details and a heightened sensitivity to the suffering of others, even if they are ants.

Apart from movies, many literary sources have delved into the relationship between ants and humans.

Empire of the Ants, a science fiction novel by French author Bernard Werber, is set in a small village in France, where mysterious events occur. The book interweaves the lives of the ants and the human characters, delving into themes of ecology, the interconnectedness of all living beings, and the consequences of human actions on the natural world.

Another story by the same title, ‘Empire of the Ants,’ was written by H.G. Wells, a prolific science fiction author. The story is set in a future where ants have evolved into a highly advanced and intelligent species. In the story, the narrator stumbles upon an ant colony unlike any other, where the ants have developed complex societies, technology, and even their form of agriculture.

The narrator observes the ants’ behaviour and their organisation, which is structured similarly to human societies, with divisions of labour, and reflects on the potential consequences for humanity. It is a fascinating exploration of evolution and the possibility of other intelligent species coexisting with humans. It offers a thought-provoking glimpse into a world where ants have surpassed humans in their societal and technological achievements.

‘Letter from a Slave-Maker Ant (Polyergus Rufescens) to the Queen of Its Anthill, Written During Its Trip Through Europe’ is a unique and imaginative short story by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish neuroscientist and Nobel laureate. The story is a fictional letter written from the perspective of a slave-making ant, a species known for raiding other ant colonies, capturing their offspring, and forcing them to serve as slaves. The story adopts a non-human perspective to critique early twentieth-century human society.

In the letter, the slave-maker ant describes its journey through Europe, observations of human societies and their parallels to the ant world, and its evolving perspective on slavery. The ant reflects on the role of the queen ant in the colony, the hierarchy of ant society, and the interactions between different ant species.

The story is a creative and thought-provoking exploration of the natural world, with the ant’s observations serving as a metaphor for human societies and their complex relationships. It raises questions about power, authority, and the nature of servitude while offering a unique and whimsical perspective on the world.

The use of anthropomorphism, attributing human characteristics to non-human entities, has been a recurring theme in the works of great artists, authors, poets, filmmakers, and researchers. Franz Kafka’s seminal work, ‘The Metamorphosis,’ exemplifies this exploration as it opens with the evocative line:

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

Kafka intentionally leaves the specific insect species ambiguous, offering readers the latitude to interpret the transformation in various ways. While descriptions such as multiple legs and a hard shell bring to mind the images of certain insects, the deliberate ambiguity underscores the surreal and symbolic nature of the transformation, inviting readers to focus on the psychological and emotional aspects of the story rather than a specific entomological classification.

The widespread interpretations of the insect protagonist reflected in the diverse covers of Kafka’s work often depict cockroaches, beetles, or generic insect-like creatures. For some, the choice resonates with the inherent disgust and aversion associated with cockroaches, arguably one of the most disliked domestic insects. For others, the creature is simply a bug.

However, an intriguing perspective emerges when considering the possibility of the transformed creature being an ant. This notion finds resonance in the theme of conformity and the portrayal of Gregor Samsa’s sense of being a part of a larger, organised society akin to the life of a worker ant in a colony. The story subtly reflects Gregor’s feelings of entrapment and alienation within his own family and society, mirroring the life of a worker ant. His transformation mirrors the loneliness and isolation he feels in his human life.

Ants are often associated with hard work and a strong sense of duty. Samsa’s transformation into an ant could also reflect the burden of his responsibilities as a breadwinner for his family and his feelings of being trapped in a life of ceaseless labour. A transformation reflecting the sacrifice of his desires and well-being for the sake of his family echoes the selflessness associated with ant colonies.

Furthermore, ants’ small and seemingly insignificant nature from a human perspective introduces another layer of interpretation. Gregor’s transformation might symbolise his perception of his insignificance within his family and the broader world. Much like ants, he may grapple with feeling overlooked and undervalued, emphasising the nuanced exploration of identity and societal expectations in Kafka’s masterpiece.

The use of anthropomorphism can be good and bad, depending on the context and the purpose it serves. Anthropomorphism can lead to a misrepresentation of the subject. When human traits and emotions are projected onto non-human entities, it can distort the reality of their behaviour and characteristics. This can lead to misunderstandings and misconceptions.

There is also a danger that while anthropomorphism can make complex concepts more accessible, it can also oversimplify them. In educational contexts, oversimplification can hinder a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

“It is permissible to say this sort of thing about humans. They do resemble, in their most compulsively social behaviour, ants at a distance,” writes Lewis Thomas in his book ‘The Lives of a Cell’. But he cautions against anthropomorphism, stating that ‘we violate science when we try to read human meanings in their arrangements.’

Ants are a testament to the wonders of the natural world. Their complex social structures, intricate communication methods, and remarkable cooperation provide endless fascination for scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. These tiny creatures, often overlooked, offer a profound reminder that there is a world of wonder beneath our feet, waiting to be discovered and understood.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to editor@madrascourier.com