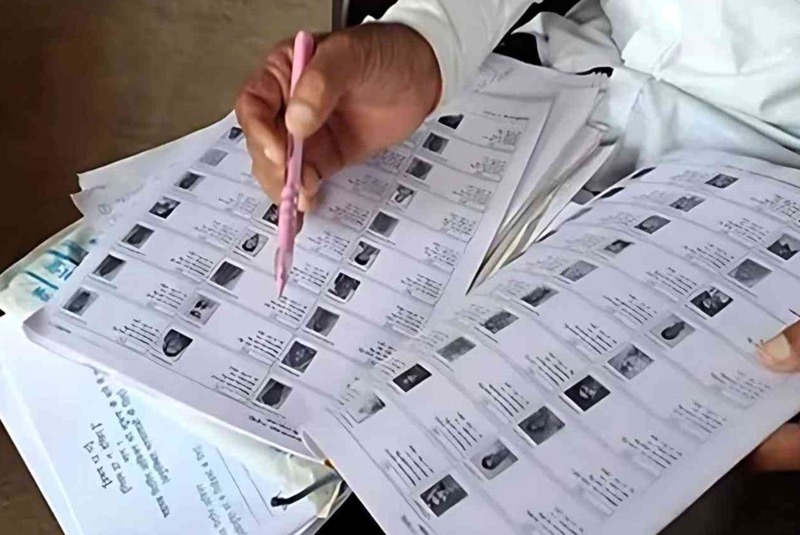

If elections are reflections of democracy, the recent developments surrounding the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) and voter roll irregularities reveal what that reflection has become—fractured, distorted, and selectively erased. The moral anxieties raised earlier were not abstract fears; they are now materialised through bureaucratic precision and digital silence.

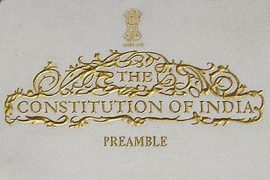

What was once a question of electoral ethics has turned into a crisis of representation. The cornerstone of Indian democracy—a free and fair electoral process built on participatory, accurate, and transparent voter rolls—is now under severe strain.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]