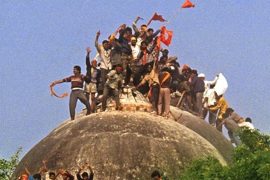

The term “nationalism” has become increasingly difficult to define, as its semantic connotations evolve as dynamically as language itself. In this gradual, often imperceptible process of linguistic evolution, certain terms can undergo a profound transformation, even to the point of semantically becoming their binary opposites. This is precisely the trajectory nationalism has followed. In its incipient phase, during the formative periods of modern nation-states, nationalism was not only considered necessary but was championed as a vital, unifying emotion. As scholars like Benedict Anderson argued in Imagined Communities, nations are “imagined political communities”, constructed through print capitalism and shared narratives. Building these nations required leaders to forge a collective sense of identity, security, and unity in the minds of the populace. Thinkers like Ernest Gellner argued that nationalism was a functional prerequisite of industrial society, creating the shared high cultures and standardised languages necessary for modern administration and economic life. Leaders, from Germany’s Otto von Bismarck to Italy’s Giuseppe Garibaldi, leveraged this sentiment to forge a sense of shared identity, security, and common destiny among disparate populations. Initially, this project was not inherently divisive; it was a parallel process of binding people to a place while other similar political entities were also coalescing. The nation thus became a potent emotion; irrefutable, sacred, and powerful. However, as political theorist Isaiah Berlin cautioned, this very power contains the seeds of its own distortion. The circle is now complete: the signified of the signifier ‘nationalism’ in contemporary discourse is often what was once its binary opposite, a force of exclusionary division rather than unifying construction.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]