Since the advent of civilisations, markets have represented the most effective social technology. They were developed by humanity to meet human needs and tackle evolving socioeconomic challenges. From barter to maritime trade, economic principles of scarcity and choice have been addressed through value exchanges in physical markets. Historically, markets functioned as tools to generate wealth and foster human prosperity; they were typically regulated by centralised systems under monarchical rule.

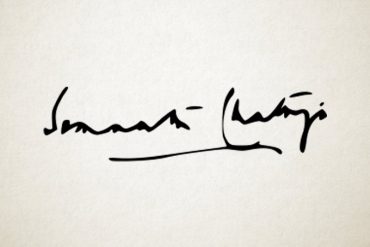

Regulated markets underwent a radical transformation ever since the publication of “The Wealth of Nations,” in 1776, by the Scottish economist and moral philosopher, Adam Smith, a towering figure of the Enlightenment. Although referenced only once in his tome, the term “invisible hand of markets” has since become the defining paradigm in economic theory and practice. The enduring metaphor was immediately patronised by liberal economists and affluent merchants, who erroneously propagated the belief that free markets are infallible and invariably lead to optimal outcomes.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]