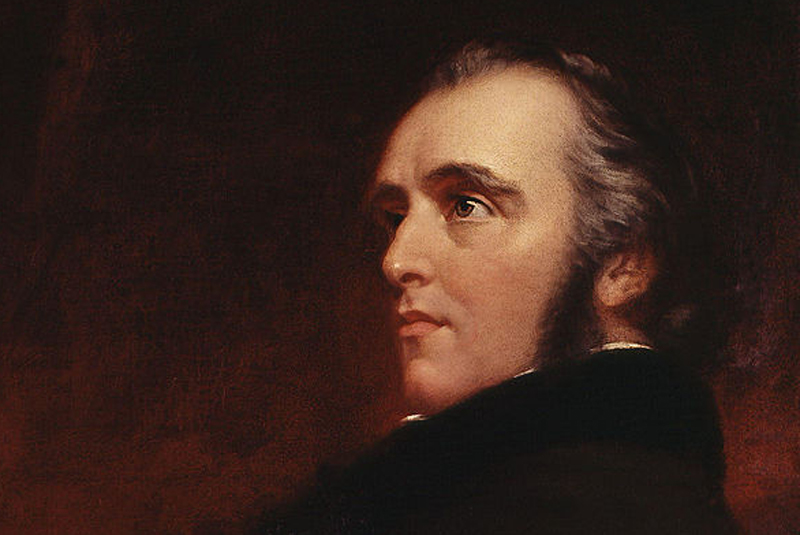

In 1834, Thomas Babington Macaulay, a bookish intellectual, landed on the shores of the Indian subcontinent. His mission was to serve on the Supreme Council of India and to advise the Governor-General, Lord William Bentinck.

Thomas Macaulay worked only for four years in this role–from 1834 to 1838. But he left a lasting legacy, imprints of which can be found embedded in the Indian psyche and language even after two centuries. However, his work and legacy were not driven by his love for India. Far from it.

He took up the job in India primarily to augment his personal income; his father, Zachary Macaulay, had faced considerable financial difficulties, leaving Thomas to be the sole breadwinner of the family. Besides, he was driven by a ‘civilising mission’– a belief that European values were superior to those of the ‘natives.’

In India, Thomas found that the British governing class had been polarised on the issue of education and the language of instruction. On the one hand, there were the so-called ‘Orientalists,’ those who wanted to study and preserve Indian languages, traditions and institutions. On the other, there were those who wanted to ‘modernise’ and transform the Indian education system and governance based on Western values and the English language. Thomas belonged to the latter camp. In his writings, he made powerful arguments proclaiming the importance of ‘superior European values’:

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]