As a person who has got the love and affection of both Indians and Pakistanis, it would be my last wish to bring the two nations together. As a poet, I want to make a humble contribution by penning a ‘song of peace that is common to both countries. It will be sung by millions of Indians and Pakistanis. It is my wish that one day the people of the two countries will sing the songs of love instead of hatred.

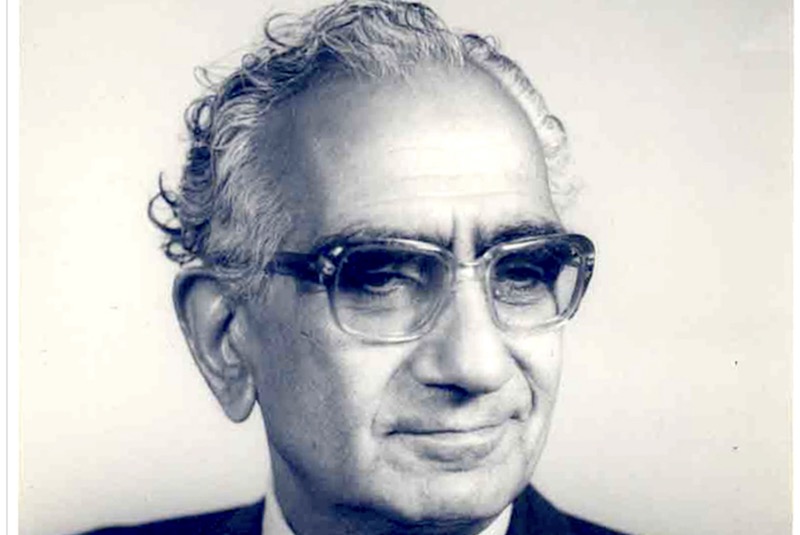

In July 2004, just before passing away from cancer, Jagan Nath Azad, an acclaimed Urdu poet, said the above lines in an interview with Luv Puri, an Indian journalist. During the interview, Azad shared a specific piece of information that surrounded him in a whirlwind of controversy in India and Pakistan. The 85-year-old Jagan Nath Azad told Puri that he penned down the first national anthem of Pakistan, Tarana-e-Pakistan.

During his lifetime, Azad was a famous Urdu poet who incessantly wrote about Hindu-Muslim solidarity and peace between the two countries. Azad was born in Mianwali, Punjab, as the son of renowned Urdu poet Tilok Chand Mehroom (currently in Pakistan). Muhammad Iqbal, better known as Allama Iqbal, Pakistan’s visionary Urdu poet and philosopher, was a close associate of Azad. Azad’s contribution to Iqbal studies is still considered one of the greatest biographical works.

During the partition, Azad was amongst the last Hindus living in Lahore. All his family had already shifted, but Azad was hesitant. Azad claimed to have received a special request from Muhammad Ali Jinnah a few days before the partition.

“On the morning of August 9, 1947, there was a message from Pakistan’s first Governor-General, Mohammad Ali Jinnah. It was through a friend working in Radio Lahore who called me to his office. He told me, ‘Quaid-e-Azam wants you to write a national anthem for Pakistan,'” he told Puri. “I told them it would be difficult to pen it in five days, and my friend pleaded that as the request had come from the tallest leader of Pakistan, I should consider his request. On much persistence, I agreed.”

During this interview, Azad did not name the person from Radio Lahore who presented Jinnah’s request. However, he remembered that “Quaid-e-Azam wanted the anthem to be written by an Urdu-knowing Hindu.”

“I believed that Jinnah Sahib wanted to sow the roots of secularism in a Pakistan where intolerance had no place,” he had said. Jagan Nath Azad wrote down Tarana, or the anthem, and Jinnah approved it in no time.

On August 14, 1947, the day celebrated as Pakistan’s independence day, Azad heard his Tarana being played on Radio Station Karachi. He said he was the only Hindu that night who had not left Lahore.

Azad’s Muslim friends did not want him to leave and took responsibility for his safety, but the communal violence in Pakistan made it impossible to do so. Azad was forced out of Lahore to Delhi in September 1947. A month later, he returned to Lahore, but “his friends advised him against staying as they found it difficult to keep him safe… He returned to Delhi with a refugee party,” Chander K. Azad, his son, told Beena Sarwar, an artist, filmmaker, and journalist from Pakistan.

Jagan Nath Azad passed away on July 24, 2004. A month later, the interview was published in Milli Gazette and almost a year later in The Hindu. Luv Puri’s article, “A Hindu wrote Pakistan’s first national anthem,” initiated a debate in India and its neighbouring country. Many in India and Pakistan were overjoyed about Jinnah commissioning a Hindu to write the anthem of Pakistan, but many questioned Azad’s legitimacy.

An article by Dawn discussed Aqueel Abbas Jaferi’s book Pakistan ka Qaumi Tarana: kya hai haqeeqat kya hai fasana (Pakistan’s national anthem: what is a fact, what is fiction). Dawn points out Jaferi to be a “pakka Pakistani” yet claims the book to argue reasonably and unemotionally.

Jaferi argues that Azad mentioned the broadcast on the Karachi station, which did not exist back then. Additionally, he finds it suspicious that Azad did not name his Lahore Radio Station’s friend and never published the Tarana in any of his books. Lastly, Jaferi argued that many wrote poems titled “Pakistan ka Tarana” after independence, but none became the anthem.

Even if Azad was being truthful, the government of Pakistan has never recognised him for writing any anthems for the country. However, the debate gets heavier on both sides. Hector Bolitho’s official biography, Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan, published by John Murray in 1954, claims that Jinnah asked a Hindu to write Pakistan’s anthem.

“The anthem commissioned by Jinnah was just one of his legacies that his successors swept aside, along with the principles he stressed in his address to the Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947- meant to be his political will and testament,” Sarwar referred to Bolitho.

It could be that after Jinnah’s death on September 11, 1948, the radical party of Pakistan objected to a national anthem by a Hindu and decided to get rid of it. Until seven years after independence, Pakistan did not have a lyrical anthem. Upon a visit from the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in 1950, the National Anthem Committee adopted a tune performed by the Pakistani Navy Band. Finally, in August 1954, lyrics from a submission by Hafeez Jalandhari were adopted as the new national anthem. The anthem was known as Quami Taranah or the anthem of the community.

When it comes to the confusion of Radio Karachi, it could have been a personal slip or an error made during the interview. In his 1981 autobiographical, Ankhen Tarastiya Hain, Azad mentioned listening to a Tarana he wrote on Radio Lahore, not Radio Karachi. He also wrote about it in Hayat-i-Mehroom in 1987.

“And one day, I discovered that I was the only Hindu left of that original population of sixty thousand. Everyone had left. In that state [of things], on the night of August 14, I heard from the Lahore Radio my own Tarana-e Pakistan,” reads an autobiographical essay of Ankhen Tarastiya Hain. “If I’m not mistaken, that was perhaps the first Tarana-e-Pakistan that reached the ears of the listeners the moment Pakistan appeared on the world’s map, i.e. at midnight on August 14.”

After the revelation of the 2004 interview, people are left behind debating the truth in the late poet’s claims while he is not around to justify them. However, throughout his lifetime, Azad promoted communal peace through his writings.

After settling in Delhi, Azad accepted the position of Assistant Editor for Milap, an Urdu daily. He assumed many editorial positions associated with the government, such as working with the Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Tourism Shipping & Transport, etc.

When the Border Security Force was formed in the 1960s, Azad was its first public relations officer. He was stationed in Srinagar, Kashmir and maintained close ties with people of all political and religious persuasions in Kashmir.

Azad was close to Mirwaiz Molvi Mohammad Umar Farooq (Kashmir’s religious and political leader) and even Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah (Prime Minister of Kashmir). Kashmiris saw Azad as an impartial thinker imbued only with the spirit of humanity rather than as a ‘government agent.’

In December 1992, Babri Masjid was destroyed. Azad was flying from Jammu to Delhi at the time. When he heard the news, he composed a poem on board, condemning the act. His poem stated that the act did no harm to Islam but hurt Hinduism. It cost the country’s reputation as a secular state.

Azad wrote over 70 books, and his works on Allama Iqbal are unparalleled even to this date. Azad wrote his biography Roodad-e-Iqbal, which remained incomplete as he passed away before publishing the last three manuscripts. The poet was highly respected in India and Pakistan for his contributions to Urdu literature—some people from Pakistan claim to remember hearing Azad’s anthem on the night of independence.

Ashfaque Naqvi, who wrote about him in Dawn, claims to have met him long before partition. He remembers the lines of Tarana going:

“Aey sarzameen-i-pak

Zarrey terey hein aaj sitaron sey tabnak

Roshan heh kehkashan sey kahin aaj teri khak”

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]