After Parvati Nimwal completed grade ten she was married off and moved to her husband’s village. Kandala is in Madhya Pradesh’s Alirajpur district, and has the lowest literacy rate in the country.

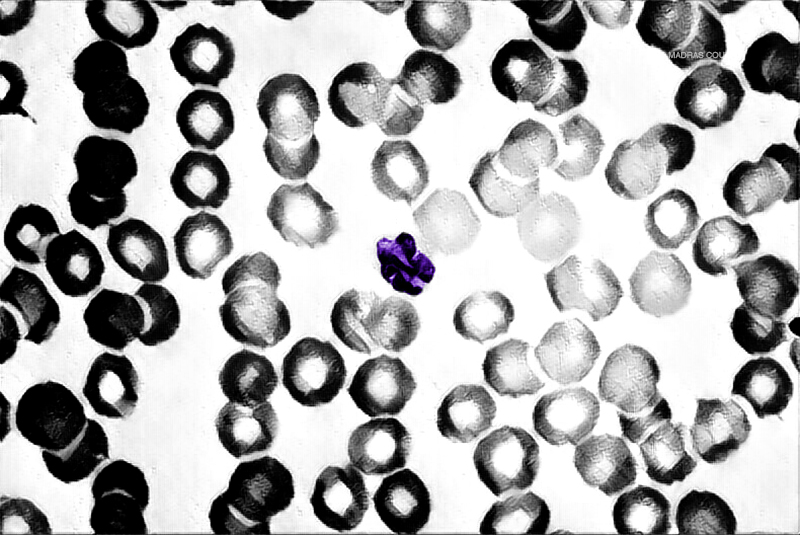

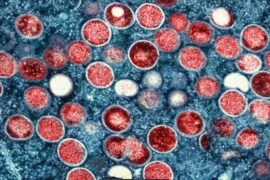

For the village leaders, her arrival left no room for argument. She was the most qualified to be their doctor, and help them tackle the scourge of malaria. Parvati was made an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA), given a few week’s training and the equipment and mandate to diagnose and treat malaria, and other general ailments. She is one of one of 900,000 such woman workers – India’s barefoot doctors who work in places the public health system cannot access (and everywhere else too).

She doesn’t know the name of the medicines she prescribes for malaria – at least, not on questioning, she laughs. She’ll have to check the textbook that the Ministry of Health and Family Planning gave her. While doubts have been cast over the efficacy of ASHA workers, there’s no denying that they’d made their impact: the death toll from malaria has been in steady decline. In 2005, it was 963. For 2016, it’s 242. The plan is for nationwide wide eradication by 2030.

Dr. A.C. Dhariwal is director of the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) – India’s nodal agency for coordinating the war on Malaria. After 13 years of implementing community healthcare across India, he says:

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]