The caste system, once confined mainly to the South Asian Hindu population, has now gone global. Dr.B.R. Ambedkar—the champion crusader against this social evil, who termed casteism as not merely a ‘division of labor,’ but consummately as a ‘division of laborers’—had prophesied decades ago that, ‘if Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, Indian caste will become a world problem.’

The onset of globalisation and liberal immigration policies in the Western world, especially the US Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, facilitated the migration of hordes of caste-privileged individuals and communities among the Hindu populace to the United States. South Asians have also migrated to the United Kingdom, Singapore, South Africa, Australia and other parts of the world.

Historically, in India, the caste-privileged communities thrived by ostracising at least seventy per cent of the Hindu population under an inhuman and mythical categorisation of fellow humans as sub-humans and ‘untouchables.’ Their historical over-representation and millennia-long social dominance were challenged by the Indian Constitution when affirmative action, providing quotas to the hitherto underprivileged and socially disadvantaged communities, was incorporated by its founding fathers. The public sector was the largest employer in post-independence India, owing to the nationalisation drive, until 1991, when the winds of change forced India to integrate with global economies through liberalisation.

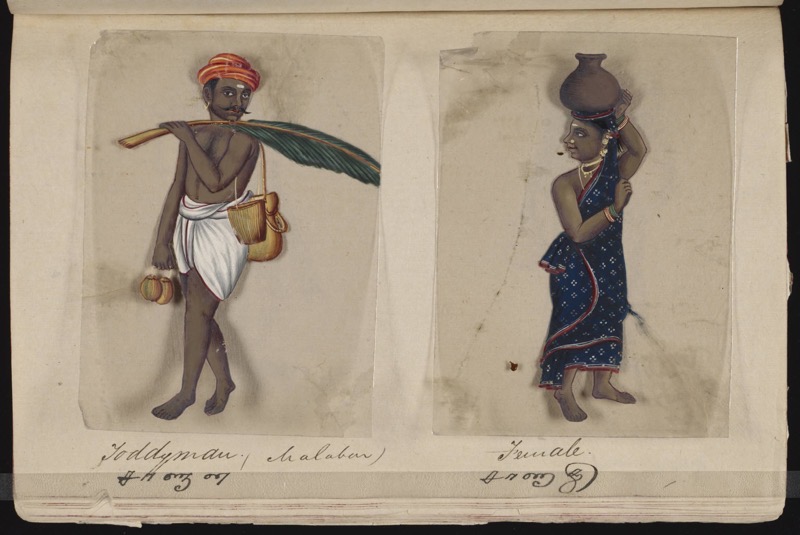

The first wave of immigration from India took place in the colonial era. It consisted of indentured labourers going to East Asia and the Caribbean. The second wave consisted of traders and clerks going to East and South Africa. If the first and second waves were populated by ‘lower castes’ in the Indian hierarchy of castes, the third wave to the Western world was exclusively dominated by ‘upper castes.’

The privileged castes who travelled to the West, travelled with the baggage of caste supremacy. There, they propagated the same historical wrongs on any lower caste ‘untouchable’ who wished to break the shackles of subjugation.

Unlike race, caste is not a protected category in the West, primarily due to the ignorance of its dynamics among South Asian Hindus. This is particularly because the Indian diaspora is a minority. Therefore, the subjugation of a minority within a minority was perpetrated subtly. It escaped the conspicuousness of social diligence and was far removed from the eyes of authorities.

To escape caste tyranny, those from the underprivileged castes chose to conceal their identities. Many were forced to lead a double life of Sanskritisation. Eventually, silence became the predominant social dictum in the fight against caste atrocities in the West.

But however many times one tries to murder the truth, it will resurrect. Such resurrection occurred with a discrimination lawsuit in January 2020, filed against two employees of the tech conglomerate, Cisco Systems Inc., by the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing on behalf of a Dalit engineer. The accused were both upper caste supervisors who were allegedly jeopardising his promotions and career prospects. Though the case against the engineers was dismissed by an order of Santa Clara Superior County Court, the litigation against Cisco for abetting such incidences is ongoing.

The plaintiff and one of the supervisors are alumni of the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology (IIT). When the Indian government extended reservation quotas for the backward classes and scheduled castes and tribes in higher centres of learning like the IITs, it was met with vehement protests and demonstrations by the privileged caste communities. And those students admitted to the IIT’s on caste-based affirmative action quotas were met with fierce opposition; they were stigmatised and ridiculed as unworthy of elite education. The overriding narrative was the ‘intellectual inferiority’ of the ‘quota students.’

The Cisco case brought caste as an oppressive category into the limelight in the US. Many victims broke free from their self-imposed cocoon to share their anecdotes of oppression from the upper castes, both in workplaces and social settings.

In May 2021, lawyers representing a group of Dalit workers filed a lawsuit against Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS) and related parties against exploitation in the construction of a temple in New Jersey. Incidentally, the workers were brought to the US on visas designated for religious workers. The complainants allege that they were paid $450 per month, less than $2 a day and made to work more than 87 hours a week, flouting US labour laws. Furthermore, they were constantly under surveillance and disallowed to leave the premises; they were intimidated and warned of pay cuts, detention, and deportation to India if anyone endeavoured to disclose this abuse to legal authorities.

If convicted, the BAPS misuse of the United States immigration laws to commit acts of ethical and moral turpitude has only one plausible explanation—that Dalits are ‘sub-human’ and ‘pollutants’ whose nemesis is irrevocably tied to Karmic cycles; that they ought to be treated as pariahs and always made to reinforce their spiteful place in mainstream social dynamics. Whose mind is corrupted and whose soul is polluted here?

While most respondents to harassment wished to remain anonymous for fear of backlash, some have commendably revealed their identities to fight against this pernicious evil. Maya, a Dalit, uses a pseudonym and works in Seattle in the tech industry. She painfully narrates harrowing experiences of living as a student; Students refrained from sharing rooms with anyone but their own caste. Such kinship extends to all facets of academic life, from securing apprenticeship in university to recommendations for employment.

During her employment, her manager was aghast when he discovered her caste status. Promptly, he denied her access to the project she was working on and sarcastically asked her to ‘not touch the project’ as she was deemed to be of a lower caste. For some who aren’t familiar with the caste system, it may be passed off as a ‘light-hearted joke.’ However, to someone whose ‘fatal accident at birth’ had endured the most vicious forms of ostracisation and seclusion for generations, such humiliation leaves a deep scar in the psyche.

Caste is essentially a closed system of social stratification. If race is about colour, caste goes deeper into the metaphysical aspect of one’s being. Some upper caste people believe that people of ‘lower castes,’ who are called ‘untouchables,’ are impure and polluting. Such malignant beliefs have led Yashica Dutt—a journalist who hails from Delhi and possesses excellent academic credentials from prestigious schools, St. Stephens Delhi, and Columbia University in New York—to conceal her Dalit origins. She has recently shed her inhibitions, pretensions, and inner turmoil of a duplicitous life by writing a compelling book, Coming Out As A Dalit, expiating herself. In it, She narrates the bewilderment and incredulity of her social circle when she audaciously declares that she is a Dalit.

A society should deeply introspect its moral compass when it is mired in prejudices about fellow human beings that are deeply entrenched by myths and tribal laws, deftly clothed as divine revelations. These markers are also a litmus test for the sociocultural progress of a society, where debates, rationality and ethical discourse must set precedence over irrational and regressive belief systems.

Bhanu Adhikari, who immigrated to Australia in 2008, suffered discrimination of a different kind. Though he is an upper-caste Hindu from Bhutan, priests from Adelaide turned down his request to perform a customary ceremonial ritual on his mother’s 84th birthday. The priest denied the service because Bhanu, being cosmopolitan in his worldview, socialised with untouchables and dined with them. This is considered an anathema for the ignorant priests.

Casteism is a gnawing reality among the South Asian population in Australia. If Karishma Luthria, a Dalit from Mumbai, was annoyed by the caste consciousness of university batchmates, San Kumar Gazmere, a fast-food manager, discerned that it was wise to change his surname for fear of seclusion from his Nepalese community in Cairns. Melbourne-based filmmaker Girish Makwana suffered caste discrimination when he was an international student in Australia. The landlord he approached for a rental house rejected his application among the five others—whom he admitted—because he is Dalit.

A dating app called Dil Mil, meaning a meeting of hearts, has options only for ‘upper caste’ suitors to explore their soulmates but none for ‘lower castes.’ It is relegated to the meeting of privileged castes rather than of hearts.

A UK government-commissioned report, instituted to study the extent and severity of caste-based discrimination, concluded that there is ample evidence of direct and indirect caste-based exclusion and harassment. This includes a Brahmin healthcare worker, employed by UK Social Services, refusing geriatric care to a Ravidassia (Dalit caste among Sikhs), Jatt (high caste Sikhs) drivers relinquishing employment in a company founded by a Ravidassia to caste slurs against Ravidassia woman in a shopping centre by upper caste shoppers, to cite a few cases. Interestingly, due to pressure from powerful Hindu lobbyists, the Theresa May government backed down from an addendum of caste discrimination and harassment from the Equality Act of 2010, where caste, in its section 9, is treated only as an aspect of race.

In striking contrast, Seattle, a bustling tech megapolis, in February 2023, became the first city in the US to enact a law against caste discrimination, followed by Fresno in California in September. Several multinational companies such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Dell, and X (ex-Twitter) have incorporated clauses against caste discrimination in their corporate policies. But Google, a subsidiary of Alphabet, received widespread condemnation for cancelling a speaking assignment on caste by Thenmozhi Soundararajan, a Dalit activist, technologist, caste equity educator and founder of non-profit Equality Labs, as part of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiative. The cancellation was triggered by mass emails sent to the management by upper caste employees in Google, denouncing Thenmozhi as ‘anti-Hindu’ and ‘Hindu-phobic.’

Activists and intelligentsia in academia and industry have suggested including caste as a protected category in the US, where almost eighty-five per cent of all American Indians hail from upper castes. Corporate policies pertinent to DEI (Diversity, Equity & Inclusion) initiatives should extend caste as a lived reality impacting many millions of individuals and communities, which currently addresses only race, gender, and sexual orientation. The Western world should eschew standard stereotypes and perceive India through a different lens.

In India, Constitutional guarantees exist mainly in letter, not in spirit. Caste remains the predominant marker of social organisation and the biggest deterrent to socioeconomic progress. India is a land inhabited by a multiplicity of people, traditions, and cultures. Still, only high-caste culture is perpetuated and propagated in Bollywood movies, media, and the entertainment industry, which reinforces dominant stereotypes. It is also a land where ancestry determines an individual’s perceived value; the presumed supremacy of a minority is juxtaposed against the presumed inferiority of a majority. In India, names don’t matter, but surnames do.

Caste is now a global phenomenon. The global manifestations of caste—toxic, noxious and destructive—are bound to impact the rest of the world. The world needs to recognise that and put policies that make caste discrimination a criminal offence.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]