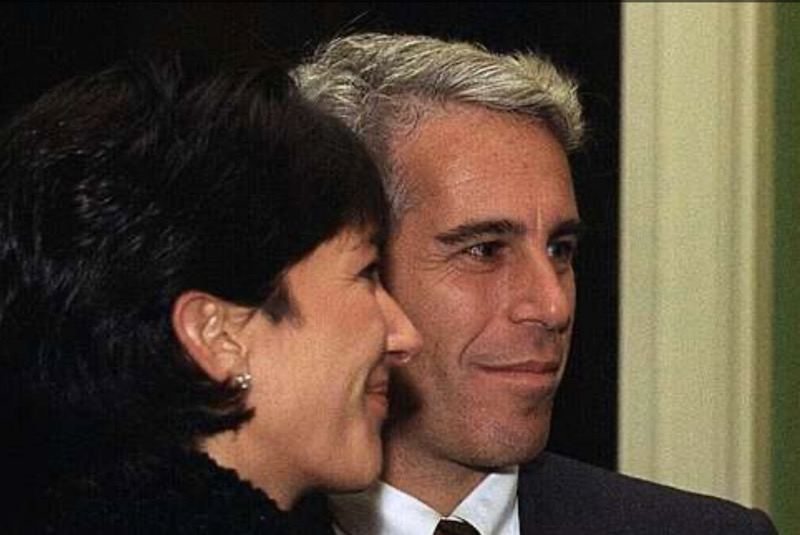

Jeffrey Epstein’s emails, released by the United States Department of Justice, reveal an unsettling social system. They show a man who understood that influence is rarely exercised through speeches or votes, but through proximity, presence, and access.

By creating spaces where powerful people could meet, mate, wine and dine freely, Epstein influenced the ebb and flow of global politics. He was not powerful in the conventional sense. He held no office, led no mass movement. What he had was access and an intuitive grasp of how modern elites behave privately.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]