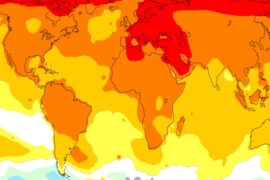

Recently, nations have been rushing to recognise the state of Palestine, marking a historic moment in global diplomacy. Yet, this gesture risks being rendered meaningless. Recognition without meaningful change on the ground risks becoming symbolic.

Under international law, a Palestinian state requires clear borders. However, these borders have been disturbed, disputed, and fragmented over decades of political conflict. Today, the challenge isn’t just recognition. It’s what that recognition will mean in the face of an increasingly disjointed and militarised reality.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]