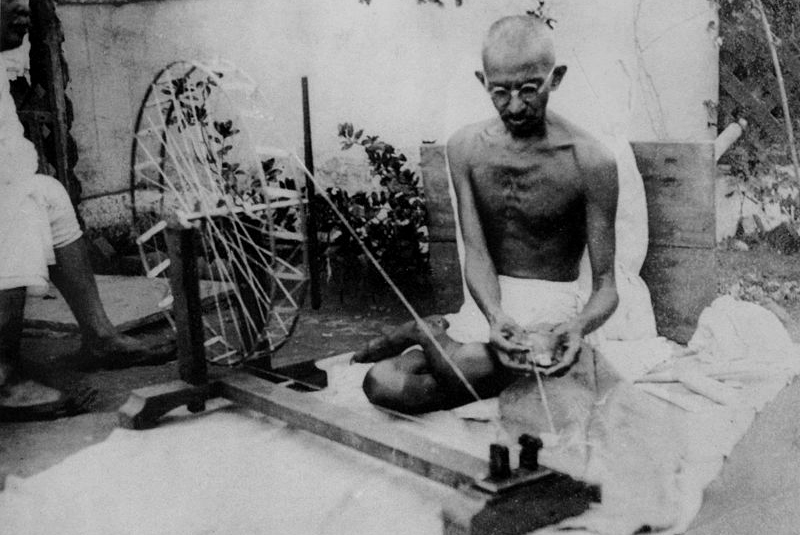

Nearly one hundred years ago, in 1918, Gandhi began a relief programme for millions of India’s poor. Sitting cross-legged beside a spinning wheel called ‘Charkha’, he spun cotton by hand.

It was a political act – with socioeconomic dimensions. In a bid to break the monopoly of British mills over Indian textiles, Gandhi encouraged villagers to grow their own cotton, and spin their own yarn. The product was Khadi – a homemade, handspun cloth that launched the ‘Swadeshi’ movement. Foreign goods and imported cloth were burned and Indian cloth was embraced.

Khadi, the homespun cloth, was an ideological weapon against the machine-made cloth imported from Britain. The device to make it, the charkha, caught Gandhi’s attention – and he wanted to scale its adoption so the Indian village could regain its lost arts.

The spinning wheel represents to me the hope of the masses. The masses lost their freedom, such as it was, with the loss of the Charkha. The Charkha supplemented the agriculture of the villagers and gave it dignity. It was the friend and the solace of the widow. It kept the villagers from idleness.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]