India’s pursuit of a formidable data privacy regime encapsulates a broader struggle to assert digital self-determination without severing vital global linkages. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), 2023, heralded as a landmark, remains an embryonic construct, an overture, of India’s sovereignty ambitions.

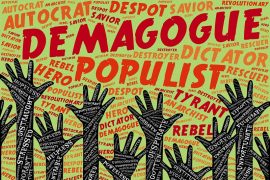

However, beneath the rhetoric of consumer rights and regulatory compliance lies a more profound quandary: Does this framework enshrine individual agency, or does it merely reallocate dominion, shifting control from foreign entities to the state’s hands? With broad exemptions for state actors, the very institution tasked with oversight risks becoming its greatest beneficiary.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]