Terrorism-related gun violence in the United States has long occupied an uneasy space in the national psyche. For decades, it has hovered between the contours of crime and ideological extremism. It is a phenomenon shaped by the country’s unique relationship with firearms and also by a long lineage of political, religious, and racial tensions that have periodically erupted into deadly force. Understanding this history requires tracing how guns became tools not merely of personal violence but of symbolic and often theatrical expression—violence designed to communicate, intimidate, and destabilise.

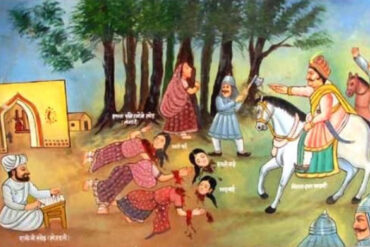

The early republic saw its first form of terrorist gun violence emerge from struggles over political identity and racial hierarchy. In the decades following the Civil War, paramilitary groups in the Reconstruction South deployed firearms to maintain white supremacy through calculated acts of intimidation and massacre. These groups, loosely organised but ideologically cohesive, turned the gun into a mechanism for asserting political order.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]