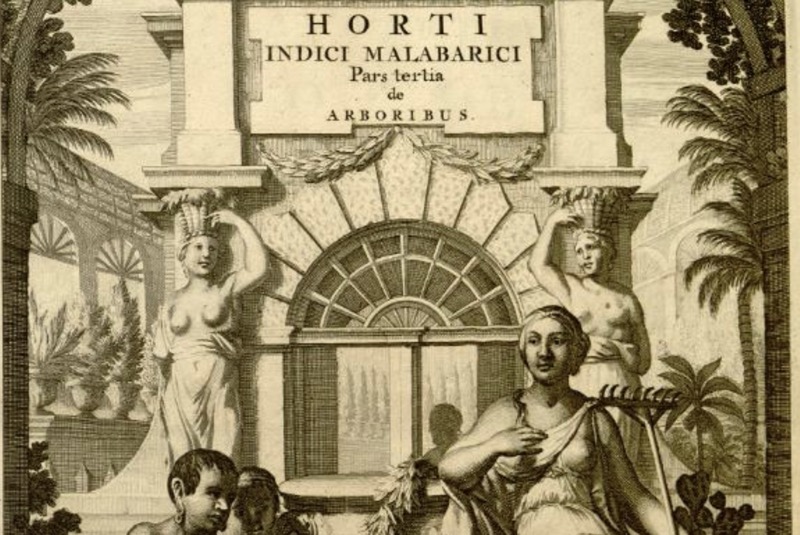

For 2000 years, ships came to India from all over the world hoping to obtain pepper and other spices. Three hundred years ago, Hendrik Adriaan van Rheed, the Dutch governor of Malabar, conducted an extensive botanical study in the Western Ghats and Hortus Malabaricus, a study in 12 volumes was published over 25 years in the Netherlands between 1678 and 1693. It became the ‘source code’ of the flora identification for those who searched for spices.

Rheed’s work contained the first paintings of medicinal plants inspired by the West. It encouraged other Europeans to conduct botanical research in India. It became a reason why artists began to document plants and animals through paintings during the advent of the British East India Company.

Flowers had a particular stance in Mughal artistry. Floral themes appeared in paintings and textiles, carpets, sculptures, metals, brickwork, and lapidary work. They often appeared as part of the design in a variety of artwork. The collapse of the Mughal ateliers by the middle of the seventeenth century prompted painters to go to other centres of power where they could obtain support.

The painters from Mughal traditions met new masters in the form of British botanists. They were commissioned to create scientifically accurate paintings of the Indian subcontinent’s flora and wildlife. A new hybrid creative tradition resulted from what they previously knew and what they were exposed to.

Artists who worked on some of the first drawings for British clients were from Patna. Some commissioned work was exotic artwork, while some were strict scientific documentaries. Lord Elijah Empey was the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court at Fort William, which was established in 1774. He lived with his wife in Calcutta and owned a private menagerie and garden to accommodate the local flora and animals. They hired Patna artists to illustrate their collection.

Empey’s project began in 1777 and produced over 300 paintings of birds, animals, insects, and plants. They are painted in watercolour on paper and featured subjects against a white backdrop.

Surgeons and physicians from the Company got interested in local remedies towards the end of the eighteenth century, searching for pharmaceutical plans and requesting their drawings for identification.

James Kerr, a Scott serving the British East India Company as an assistant surgeon, was assigned to Bengal and Bihar in the early 1770s till the early 1780s. Inspired by Hortus Malabaricus, Kerr commissioned over 660 plant drawings.

Kerr had an undergraduate degree from the University of Glasgow, where he first found his interest in nature and began studying it. He served as a surgeon on ships Cruttenden twice, during which he visited Bengal in 1765-67. On the third trip, he stayed back in 1772.

Kerr spent the majority of his time in Patna from 1774. Aside from being a surgeon, Kerr was a successful textile merchant. He was a man of many interests, as his collection at the Natural History Museum in London revealed musical artefacts. Since he lived in Patna, it is not surprising that many paintings in his collections are by Patna artists.

Kerr’s botanical drawings intended scientific illustrations to identify and describe plants for potential medical or commercial use. Kerr’s two collections of plant drawings are known today. The first set contains three volumes with 559 paintings of plants using the watercolour medium. The second collection contains 101 (or 109) copies of the former.

Kerr’s drawings have a vivid colour palette with the same poetic delicacy as Mughal flower artistry. The work demonstrates the impact of European Botanical illustration techniques as well.

Another popular set of botanical paintings by Indian artists is in the collections of Claude Martin. An army officer by profession, Martin liked to be called a ‘nawab.’ He was a philanthropist and a businessman and commissioned almost 600 plant portraits found at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, Greater London.

Martin came to India in 1751 and fought against the British East India Company in the French Army. However, in 1763, he joined the Company as a Major General, forecasting a brighter future. He lived in Lucknow until he died in 1800.

While fulfilling his military obligations, he maintained a yard in his residence at Lucknow. He was an avid collector of plants and seeds and would send exhibits to the Calcutta Botanic Garden.

The Scottish historian William Dalrymple declared Martin to be the first to employ artists of Lucknow to make sketches of flora and fauna. Like the artists from Patna, Lucknow painters were previously employed by the Mughals and had their traditional edge. Martin imported stacks of drawing paper from Europe in the early 1770s and asked the artists to replicate the Western style.

Martin knew the Empeys, and his works displayed at Kew are from when the latter commissioned Patna artists for their collections. The Martin paintings record diverse styles, some simple, while others are closer to the European style. Most portraits focus on the herbal plants in the plains and gardens of Northern India. A letter from a surgeon working in Lucknow educated Martin and praised one of the sketches.

‘My dear Martin – the flower is very well done. It is called in botany by a pompous name, the Gloriosa superba, and is, I fancy, the most beautiful of all the lily tribe,’ he said in a letter stored at the Royal Botanic Gardens.

Nawab of Awadh, Sir Gore Ouseley, acquired paintings from Martin during his time in Lucknow and passed them on to his son, a music professor at Oxford. Later, the Royal Botanic Gardens purchased them along with Ouseley’s European collection.

Even after retirement in 1776, Martin often fought with the troops in wars such as the Third Mysore War against Tipu Sultan. Martin earned a fortune from his side businesses and service in the Company. He allocated most of it to set up educational institutions in India and France. His legacy is two La Martiniere Colleges in Lucknow and Kolkata.

Kerr, Martin, and the Empeys are examples of many Europeans who employed Indian artists to paint botanical specimens. Many Company officials took part in documenting India’s natural history. Fine arts and scientific documentation had become synonymous, bringing about a distinct change in Indian artistry.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]