On the morning of April 18, 1955, Albert Einstein, the man who had unravelled the fabric of the universe with his theory of relativity, passed away in Princeton, New Jersey. His death, caused by a ruptured aorta, marked the end of a life that had reshaped our understanding of space, time, and reality.

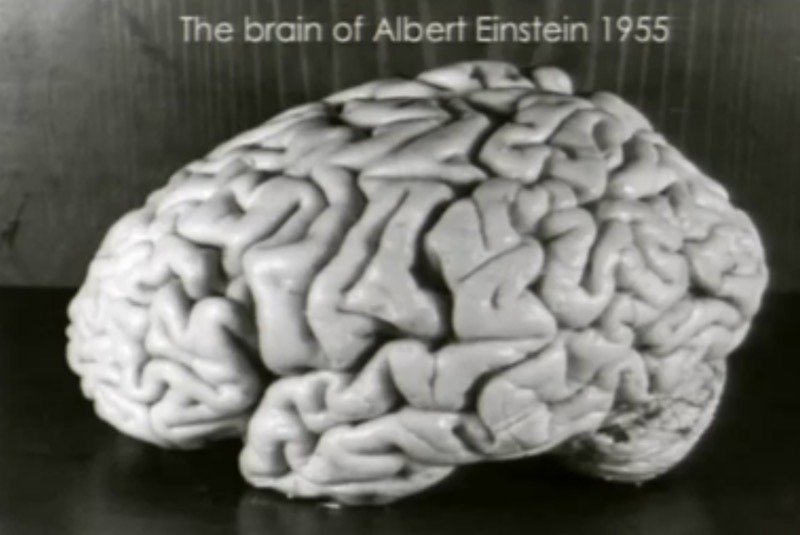

But what followed in the wake of his passing was far from ordinary. His brain, that most celebrated organ, would embark on a strange journey. This journey would outlast even his legendary genius and raise uncomfortable questions about ethics, autonomy, and the meaning of scientific curiosity.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]