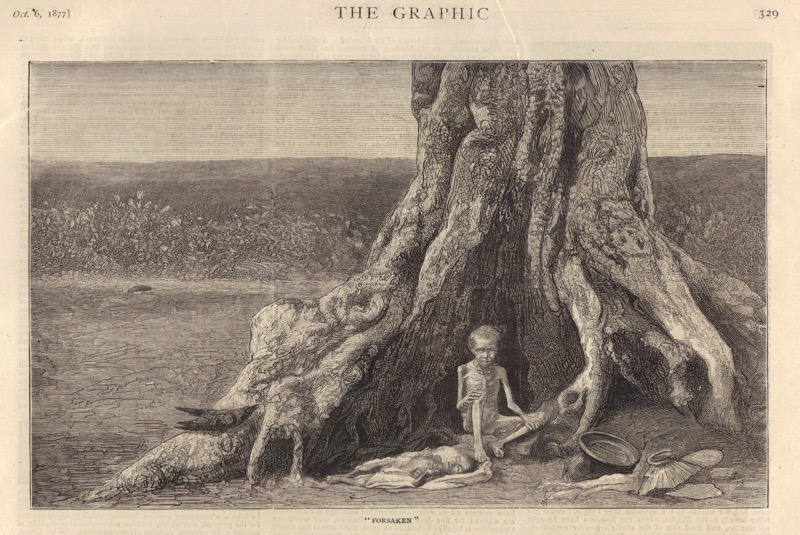

Thomas Robert Malthus, a political economist, once claimed that “Famine is the last and most dreadful mode by which nature represses a redundant population.” He referred to famine as a “positive check,” a natural way of dealing with overpopulation.

His statements were not merely theoretical; they were designed to make famine appear as a natural disaster—one that was beyond the control of any colonial government. However, a troubling question lingers in the wake of such statements: who decides which population is deemed redundant or expendable, deserving to be neglected and left to die? The answer, though complex, is both simple and harsh: those who hold political power and capital are the ones who decide who lives and who does not.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]