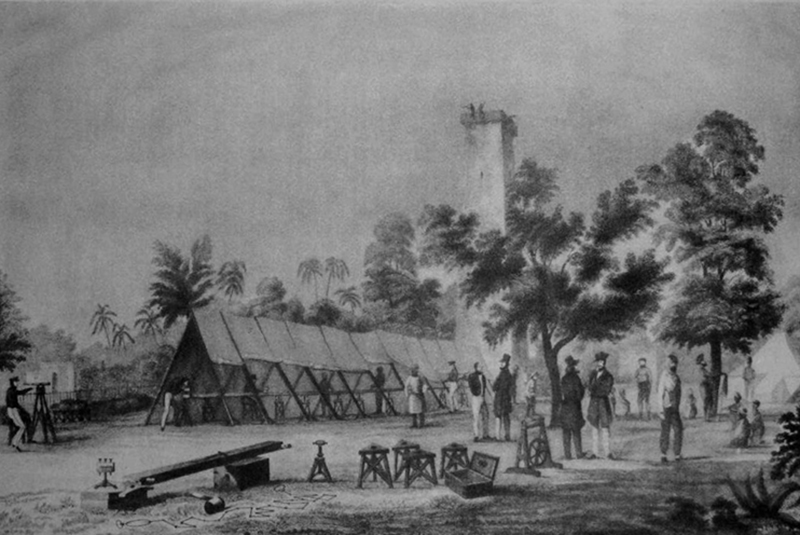

In the late 1700s, the British East India Company undertook a series of surveys in undivided India to obtain precise geographical knowledge about the territories it would rule. The company commissioned these surveys under the aegis of the infantry officer and geographer, William Lambton;

They were divided into four different categories: topographical surveys that would provide information on natural and manmade features of land; trigonometrical surveys to calculate heights, distances, latitudes and longitudes; marine surveys that would provide valuable information for the shipping economy; and revenue surveys that calculated patterns of land-ownership by the Indian people.

The East India Company believed that the surveys were necessary for accurate revenue collection, planning for economic growth, and military dominion; therefore, an investment in cartography was deemed urgent and necessary.

Between 1802 and 1815, Lambton mapped the territories between present-day Goa to Masulipattinam (Machilipatnam), a town in Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh, and from Cape Comorin (present-day Kanyakumari) to the southern tip of the Hyderabad State. Lambton, who eventually became the Surveyor General of India in 1830, used a method known as triangulation; it’s a procedure of arriving at the location of a point by forming triangles from other known points.

Thanks to the use of mathematical formulae that had to do with triangles, especially right-angled ones, the series of surveys undertaken by Lambton and others, collectively came to be known as the Great Trigonometric Survey of India. An article titled, “The Great Trigonometric Survey of India in a Historical Perspective” by Rama Deb Roy, published in the Indian Journal of History of Science (1986), brings forth Lambton’s methodology.

He visualized that the country conquered by arms is connected from sea to sea, from the Malabar Coast to the Coast of Coromandel by an uninterrupted series of triangles, and of continuing the series to an unlimited extent in every other direction.

In 1830, George Everest succeeded Lambton as the Surveyor General of India. George, contrary to popular belief, neither discovered nor surveyed Mount Everest. It was Radhanath Sikdar, the Bengali Mathematician, who accurately measured the height of Mount Everest. You can read Radhanath Sikdar’s story here. In June 2004, the Department of Posts, Government of India issued a stamp to commemorate Sikdar’s contribution.

At the time of the survey, Mount Everest was called Peak XV. However, George Everest’s protégé, Andrew Scott, wrote to the Royal Geographical Society in March 1865, proposing that the indomitable peak be named “after my illustrious predecessor.”

The Great Trigonometric Survey is credited with having measured the heights of 79 Himalayan peaks; they include the Everest, K2, and Kanchenjunga. It also measured the baselines of St. Thomas Mount, Madras, baselines of Calcutta, Coimbatore, Tanjore, Guntur, the measurements of the Cauvery Delta, the measurements of Mysore, and the Great Indian Arc – an arc extending from the tip of the Indian subcontinent to the mountains of the Himalayas. The measurement of the Great Indian arc is a significant milestone for Indian geography because it was one of the first efforts to plot, in mathematical terms, the vastness of the subcontinent from the north to the south.

In 1877, Colonel Walker merged the streams of surveys – the topographical, trigonometrical, marine & revenue – under a single stream, the Survey of India.

The Legacies of the Spy Explorer – Nain Singh Rawat

In the late 1850s, the Tibetan region under the administrative rule of the Qing Dynasty was the only Himalayan region that was free from British rule. The British had their eyes on the territory. Long before its expedition to Tibet, between 1904 & 1905, the colonial state deemed it necessary to survey the area.

However, Tibet, on its part, forbade the entry of foreigners; it closed all its political borders and trade routes including the trade roads through Nepal via India to safeguard their gold fields and prevent Chinese incursion. So, the office of the Great Trigonometric Survey of India, Dehradun, recruited several officers to survey the trade routes running from Nepal to the Tibetan region. One of them was a man named Nain Singh.

It was a dangerous mission, for the Tibetans punished foreigners with instant death. Before venturing into such dangerous territories, the survey office trained Nain Singh Rawat and his cousin Mani Singh Rawat in the use of scientific instruments and the art of disguise.

Nain Singh was born in Milam village, and in his childhood had lived at the foothills of the Milam Glacier in present-day Uttarakhand. Owing to extreme cold, the region is habitable only between June and October. Nain Singh had spent the rest of his time trekking in the western regions of Tibet, especially Gartok (currently called Garyasa), situated on the banks of river Indus, between Leh and Shigatse. These excursions to Tibetan lands had made him familiar with the language and customs of the Buddhist country, something that hugely benefitted him when he became a ‘spy explorer’ of Tibet for the British.

In 1862, Nain Singh ventured into Tibet in the guise of a Tibetan monk. He calculated the location and altitude of Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and mapped the vast Tibetan landscapes and its many rivers.

He joined an entourage of monks and recorded distances by using a rosary; for instance, the passage of a single bead between thumb and forefinger accounted for ‘x’ number of steps. The exact numbers are unknown, but he was trained to maintain a pace such that he could complete one mile in 2000 steps. He wrote his notes on the same parchments that were used to write prayers; these scrolls were then hidden within the cylinders of a prayer wheel to prevent suspicion.

For his role in the secret cartographic expedition as part of the Great Trigonometric Survey, he was awarded the Patron’s Medal by the Royal Geographer’s Society in 1877. The Society also published several articles about him. In 2004, the Department of Posts, Government of India, issued a stamp commemorating his contributions to cartography; in 2006 a three-volume biographical account, Asia ki Peeth Par, that chronicles his travels through Nepal and the hinterlands of Tibet was published by Pahar in Nainital.

Although the East India Company estimated that the surveys would not take more than five years, in reality, they took more than 70 years. They lasted through the Indian Rebellion of 1857 & until the Indian territories passed to the Crown from the Company.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]