Some fashions never go out of style. In India, the Sari has been the quintessential woman’s garment since 2000 B.C. With five-to-eight metres of cloth, over a hundred different ways to wear it and an infinite pallet of colours and fabric, what makes a Sari is an intention behind it.

For many women, putting it on is a rite of passage. Every ceremonious occasion demands a sari, perhaps to the detriment of a first-time wearer yet to fall head over heels for the voluminous and initially unwieldy garment. But like all arts, it grows on you over time.

What makes the Sari so much more than just a garment?

Social meaning

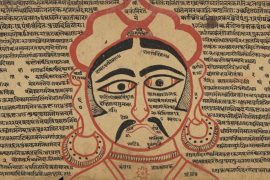

The Sari was important enough to be depicted in art as far back as the Indus Valley civilization – where a sculpture of a temple priest wearing what looks like a prototype sari was found (circa 2800-1800 B.C.).

By the sixth century A.D., Saris were common in depictions – from deities to dancers. By this time, distinct styles of Saris emerged in North and South India. But had they acquired function?

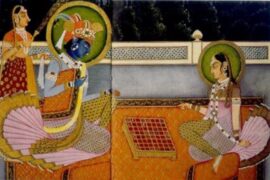

The legend of the Mahabharata features a magic sari in prominent role – when the Kaurava called Dushasana tried to pull off Draupadi’s Sari, Krishna intervened – making the fabric infinite in length, spinning her around as the hapless assaulters found themselves tugging at eternity. It was an early protection of modesty – something the Sari is often praised for.

Initially, it was a bottom-only garment that left one’s top uncovered. But veils of privacy eventually came calling – a scarf wrapped around the head that later became the face veils (Ghoongat). The loose end of a Sari, called Pallu in the Nivi style can also be draped over the shoulder or adjusted to hide the navel. Yet, the Sari has continued to transcend barriers of caste, religion, region, race and – gender.

With so many ways of wearing it, a Sari became a potent tool for communicating status. In Mukulika Banerjee and Daniel Miller’s ‘The Sari’, they call it a ‘lived garment’ – one that shapes and represents the aspirations, goals, and self-image of the Indian woman. Their book is a collection of stories where the Sari is both character and plot point.

Scholars have debated whether the Sari was a garment of modesty or sexuality. It could both hide and accentuate a figure, yet its imposition on young girls could also be seen as an act of repression. Indo-Mauritian writer Shakuntala Boolell crafted a story of defiance around the Sari. In “La femme enveloppée”, a young girl rejected the Sari as a tool of oppression during her childhood – but a forced marriage at the age of 12 made her relook at the garment. She saw that women wore were layers of prejudice and imposed beliefs – but the layers of the Sari itself could be a shield against the same.

It’s a situation that one has to have worn the Sari for to understand. It becomes a shield and a mace all at once – defending one’s modesty but also projecting one’s power.

Indira Gandhi was famous for her Saris – often simple khadi designs sourced from local weavers across the country. She had a careful colour palette and wore what suited her mood. It became an inseparable part of her visual identity – visible in her photographs with the most powerful people on earth.

As India’s most powerful woman, her death left the question of legacy to her daughter-in-law. Sonia Gandhi, though Italian-born, found her identity in a Sari. In a powerful act, she wore the same pink Sari at her wedding that Indira had worn for her own. Not to be outdone, Priyanka Gandhi also followed suit when she married Robert Vadra. It’s not just the Gandhi’s women who wore it like armour – Jayalalithaa is rumoured to have worn a bulletproof vest under her own.

Besides expressing one’s identity, the Sari is also a respite of practicality.

Versatility

There’s a reason women of all social classes choose the Sari as their daily wear. It can be immensely practical – enough so that heavy-lifting women labourers are usually adorned in one. The many ways to tie it around allow them to carry their children with them while they work, breastfeed in privacy and keep a collection of other items on their person without the need of a bag.

This versatility is by design – a popular folk legend about Sari’s origins revolve around a weaver who sought to incorporate all aspects of a woman’s personality into a new type of garment.

The sari was born on the loom of a fanciful weaver.

He dreamt of Woman.

The shimmer of her tears.

The drape of her tumbling hair.

The colours of her many moods.

The softness of her touch.

All these he wove together into many yards.

And when he was done, the story goes, he sat back and smiled, and smiled and smiled.

The story makes the Sari a creation for man’s eyes. And in many contemporary accounts of how to wear one, we see that the male gaze has yet to be averted. Articles encourage women to use Saris to hide their figures if they’re ‘Size Ten’ or flaunt themselves if they’re ‘Size Zero’. As many women have found, the Sari can do both – but its function is not exclusive to body image.

Articles abound today on rediscovering the Sari in the urban age – as women increasingly take the Sari out of the realm of ceremony and back into the everyday. The style worn by Air India hostesses has become a fashion, adopted also as the ‘Corporate Sari Drape Method’.

The Sari is India’s most iconic garment yet. If you know how to speak its language, it can be an encyclopaedia of emotions – from the first drape of a wedding Sari to the white folds of a widow’s; from the designer runway at Paris to the podium at the United Nations – the Sari has been wherever India’s women have been. If the last few thousand years are anything to go by, it’s here to stay.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]