What is unique to the national flags of Dominica and Nicaragua? It might not be evident at first glance, but both feature the colour purple. No other national flag does so.

Red and Blue have been the symbols of power and aristocracy for as long as civilisation can recall. While Red is psychologically proven to influence and intimidate others, blue is a natural rarity.

The colour red has been evolutionarily hardwired in our psyches to represent blood, and in primaeval times, the redder one, whether it be because of his adeptness at killing animals or due to his tart pink healthiness, made for a more suitable mate and a formidable, fearsome foe.

Besides the fact that it scatters less and is visible further, this instinct has been exploited in using red as the ideal colour for danger signs. The evolutionary paradigm of the superiority of health, hunting, and courting for mating choices has been used to justify why the colour is daunting and coercing—it evokes strong feelings of reverence. In contrast, in suitable contexts, it evokes sexual attraction and provocation.

The psychological effect is so profound that it has been linked to the choice of ties for Presidential nominees, mayoral candidates, and other electoral hopefuls. The colour red has been well-established to appeal both imperially and sexually.

On the other hand, the colour blue rarely occurs in nature. Even when it does, it is not a blue pigment but rather colourlessness, giving an illusion of Blue by scattering light (akin to what happens with the sky or water).

Blue’s association with the aristocracy runs more than skin deep, so much so that it crept into our parlance; “Blue Blood” is a classic idiom for nobility. Its origin is said to be the fact that the fair-skinned plutocratic elite had their blood vessels visible underneath the complexion-free skin.

As veins that carry deoxygenated blood are superficial, they appear dark bluish-green. It is thus no wonder that the combination of these two — the colour of might and valour and that of nobility and eliteness — the colour purple would be a symbol of pride and clout. However, while red and blue are widespread and recurrent colours in national flags, purple is seldom encountered.

The flags of the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, two tiny Central American nations, are the only ones in the world to feature this elusive, enigmatic colour. Why would nations forged in a world dominated by colonial rivalry, jingoism, megalomania, and imperial assertion not feature this glorious supremacist hue on their insignia and emblems?

To seek an answer, we will turn to chemistry rather than vexillology, remembering that the Nicaraguan and Dominican flags were first created in the twentieth century.

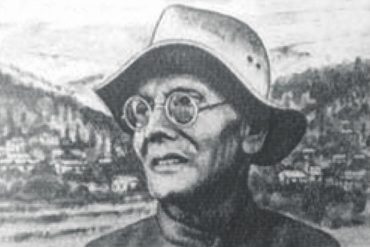

In the mid-nineteenth century, an ignominious lab assistant was cleaning up in the after-hours. In the wake of a dismally failed experiment, a beaker was encrusted with an indelible dark muck.

Trying various solvents to get the stains to yield to little avail, he noticed that upon dilution with alcohol, the residue left stark purple impressions. Thenceforth, he devoted his endeavours to fastidiously refining this substance and obtaining a usable purple pigment called ‘mauvein’, a rarity in the era.

This figment of chemistry revolutionised contemporary society. While the Orient and the occident had various purple natural dyes — for example, the traditional patachitrakars of Bengal in India used Jamuns (Java Plums, often called Indian blackberries) to paint vivid purple figments in the art — mass-production was infeasible.

Perkin’s discovery overhauled sartorial paradigms. It immediately overthrew the erstwhile-prevalent fashion norms and brought forth a watershed inflexion in the textile industry—a London dressed in shades of grey and brown now flaunted shades of purple and its derivatives.

Until Perkin’s innovation, which had him knighted and counted amongst the greatest serendipitous scientific discoveries alongside the microwave, X-rays and penicillin, purple was the sole prerogative of the rich. It was a plutocratic entitlement for those who could pay for this rarity.

Perkin’s process made purple dye production inexpensive, and fashionistas took to this readily available hue. It took the nation by such storm that even Queen Victoria wore a mauveine-dyed gown to the Royal Exhibition of 1862.

The discovery also ushered in a flurry of research by other researchers to develop various aniline dyes, a comparatively commercially convenient class of chemical pigments.

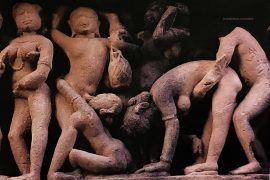

Purple was the characteristic hue donned by Roman magistrates; it became the imperial colour worn by the Byzantine emperors and that of Holy Roman Imperial regalia, consequently adopted by Roman Catholic Bishops. Likewise, the colour is traditionally associated with the Japanese Emperor and the feudal aristocracy.

Despite its symbolisms, iconography, and motifs, the abject disparity of actual purple owes to a lack of viable natural sources. Like its parent colour, blue, purple is quite rare in nature. An odd melange of peculiar sources was used to obtain it in antiquity.

In fact, the very word ‘purple’ is derived from the Old English word purpul, which derives from Latin purpura, in turn from porphura, the Greek nominal for the Tyrian Purple Dye produced from mucus secreted by the spiny dye-murex snail, a predatory sea-snail. From being a liturgical colour representing piety to being the colour of the ticket for the coronation of the British Queen, purple is an optimum of aggression and elite exclusivity.

Delving into the intricacies and subtleties of the crucial distinction between purple and violet would distract us from the cultural themes. At the same time, additional terms such as mauve, fuchsia, and lavender will add to the confusion.

However, as a fleeting, grossly unnuanced note to the reader, violet occurs on the spectrum with a definitive wavelength, while purple is a mixture of red and blue. The colours are definitively distinguishable by a phenomenon called the Bezold-Brucke Shift, whereby violet, upon being brightened, gradually tends towards blueness. At the same time, purples do not exhibit such a biased approach.

The earliest encounter of purple is in Neolithic cave paintings dating back to about 16000 to 25000 BC, coloured using manganese sticks and hematite powder. Thereafter, we encounter the rich Tyrian purple in numerous Greek accounts.

Everyone—from characters in Greek Classics such as The Iliad to Alexander the Great—wore purple. It was used extensively for decorative purposes and upholstery embellishments in grandiose ceremonious and celebratory events.

Two cities on the Mediterranean coast were said to have thriving, flourishing purple dye production trade, a fact practically corroborated by contemporary shell mounds of the murex snail. At the ancient sites of Sidon and Tyre, mountains of discarded snail shell remains were found. The production was a tedious and tantalising process.

The snails were soaked for a long time, and then a minuscule gland was excised. The excision was followed by juice extraction and subsequent exposure to sunlight. In the sunlight, the juice went through a series of colour transformations, turning, in order – white, then yellow-green, then green, then violet, then red, which intensified in darkness with the advance of time.

The process had to be ceased at precisely the right time to obtain the desired colour, i.e. the reaction progress had to be abruptly halted at violet by removing the vat/basin from the sunlight and placing it in the dark, lest it disintegrates to scarlet or further maroon. Despite such meticulous endeavouring, the exact shade varied between crimson and violet, but it was always vibrant, bright and lasting.

When the German chemist Paul Friedlander tried to recreate Tyrian purple in 2008, he required 12,000 molluscs to produce 1.4 ounces of dye, enough to colour a pocket handkerchief or napkin solidly. In the year 2000, a single gram of Tyrian purple made from 10,000 snails following the original formula cost two thousand euros.

In the Biblical Old Testament, God demanded Moses devote purple, blue, and scarlet clothing to him, among other offerings. King Solomon is said to have solicited artisans from Tyre to decorate the Temple of Jerusalem with purple adornments.

Roman bureaucracy and royalty donned purple-bordered togas. Purple sashes were common in Europe as regalia. In ancient China, the purple gromwell plants were the source of the prized dye. The abstraction did not readily adhere to fabrics, making thus-dyed fabrics quite expensive.

Byzantine empresses gave birth in the Purple Chamber, and the emperors born thus were entitled “born to the Purple” to distinguish them from their counterparts who won or seized the imperial title through political manipulation or military force. In popular culture, kings were often depicted in purple robes, a characterisation as salient as the symbolic orb and sceptre.

Akin to an elusive shade of its parent colour – ultramarine Blue, which is named so, as for centuries its sole source was pulverised lapis lazuli sourced from mines in Afghanistan (located beyond the seas concerning Europe, hence the name ultra-marine), purple was expensive, elusive and the subject of intrigue. Its longstanding virtue pervaded all spheres of life.

Linguistically, they lent idioms such as “purple patch” and “purple passage,” meaning a stroke of good fortune. The purple amethyst gem became synonymous with luxury. It was highlighted as part of their crowns, sceptres, and finger rings. Bishops adorned amethyst rings—a colour that testifies to royalty and sworn allegiance to Christ.

Catholic clergymen donned amethyst keystones in their crosses because they implied ecclesiastical piousness, chastity, and celibacy. A firm believer in Christian mysticism, alchemical, and occult practises and rhythms until the very end, Isaac Newton could have been influenced by its myriad associations, too.

Besides the belief in mystical patterns and spiritual subjectivism of musical octave notes corresponding to the number of spectral colours, it might have motivated him to forge and force into the spectrum the superfluous colour Indigo, which then stood for our current conception and perception of “blue-purple or blue-violet.”

Today, purple has become the muse of psychedelic artists. At the same time, the early 20th century saw it become a symbol of social change, perhaps owing to its peculiar unnaturalness and the eclectic intersectionality of blue and red, colours often assigned to contrarian viewpoints and competing factions.

Blue-and-red themes frequently depict conflicting ideologies or irreconcilable warring sides in pop culture. Hence, purple stood for feminism’s viewpoint of integration, mutualism, cooperation, and harmonisation pitted against patriarchal and innately masculine tendencies of cutthroat competition, monopolism, maximisation, and a desire to dominate.

Besides the white of peace and the green of prosperity and environmentalism, it symbolised the female Suffrage movement – which in turn came to be paid tribute by being adopted as the colour of the feminist movement in the United States. The hermeneutic journey of purple constitutes a long lineage of cultural themes and subconscious motifs, capturing the essence of social symbology and civilisation’s ascription of value.

The story of a single colour acknowledges the dynamism of culture and testifies to its proneness to the singular vagaries of human society. From Perkin to Pankhurst, the story of purple encapsulates axiology, sociology, psychology, and whatnot. The colour’s nuances can help us understand how science ushers in accessibility, how equality adds colour to our world, how susceptible our subconscious is, how scientific phenomena manifest in sociocultural constructs, and how the concept of “value” can change by singular incidents. The Colour Purple is a testimony to human curiosity, diversity, synergy and endeavour.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]