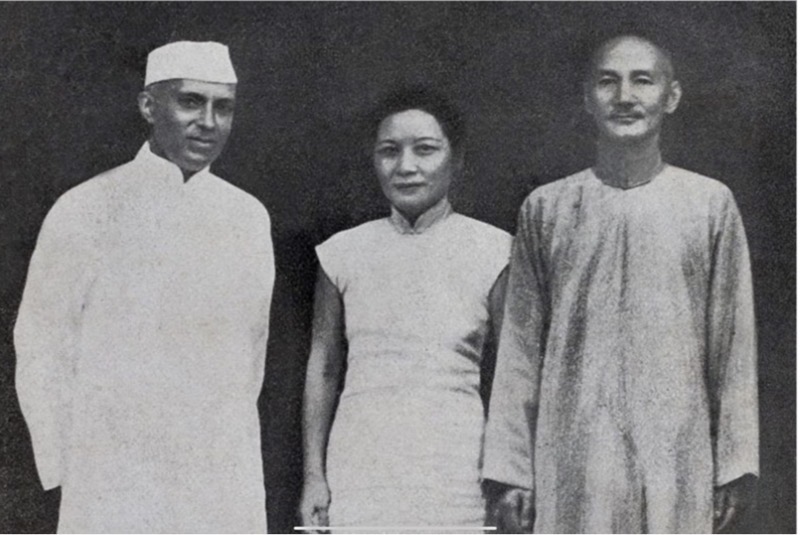

Six weeks after India gained Independence, Nehru signed a confidential agreement with the United States of America. The agreement permitted aerial missions in Tibet to continue and expand to help Chiang Kai-shek against the communist forces of Mao Zedong.

China, insecure that India was carrying the British legacy, felt Tibet was vital to China’s security. When the new Communist government took power, taking over Tibet was a high priority for them.

In the twentieth century, when China was weaker due to the disintegration of Manchu, Tibet was under British rule, and Tibet was considered “China’s backdoor.” At the time, India, in its wisdom, supported the nationalists, Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT).

Before the mid-twentieth century, India and China did not have a deep relationship. Tibet served as a buffer between the two countries, and there were no shared borders to fight over. There was even some trade over land and sea and the occasional exchange of scholars and pilgrims. But China viewed India as an underling. They supported India’s independence movement but did not want the country to rise and share the podium of influence in Asia.

India, on the other hand, unwilling to start a conflict with China, trod cautiously. India did not want a war, particularly after a tiresome fight against colonialism and continuous violent struggles with the newly formed state of Pakistan.

Nehru believed Tibet should be an independent country. To that effect, he separately invited Tibet to New Delhi in March 1947 for the Asian Relations Conference. Yet Tibet was not listed as an independent country. However, Nehru’s sympathies did not exceed the point of risking India’s relationship with China.

The United States tried to pressure Nehru to support the Tibetan cause. But Nehru, being his own man with an astute sense of diplomacy, agreed only to supply a fair sum of arms. In 1949, Nehru extended the American-Indian secret agreement of aerial missions from the initial two years to an indefinite time. But still, Nehru, the pragmatist, knew Tibet’s fate and accepted it. Nehru faced much criticism for not playing a significant role during the Chinese invasion of Tibet from within.

Tibet and India share a deep-rooted cultural and religious relationship. Indians had religious ties to Tibet. According to mythology, the Hindu deity Shiva resided at the Kailash Mountain and Man Sarovar, which are within the Tibetan border.

Moreover, the Dalai Lama was widely celebrated as a holy figure in India. The present Dalai Lama declared that Tibet belonged to India more than it ever did to China. Consequently, when the Chinese army attacked Tibetans, India provided refuge to them.

China was consolidating its position in Tibet after the occupation in 1950, and India reluctantly witnessed as the young and helpless Dalai Lama was imposed with the Seventeen-Point Agreement. China, which was constructing roads for easy access to the Tibetan territory, convinced India through vague diplomatic tactics to construct a road across the Aksai Chin Plateau, a region under India’s claim.

Nehru wasn’t completely disarmed. While he did not expect any armed conflict, he could not undermine the possibility that China would try to occupy disputed areas such as regions of Ladakh and the areas of the present-day Arunachal Pradesh, including Tawang. India did not openly support the UK and the US to loosen China’s grip over Tibet but confidentially agreed with the United States upon mutual defence in March 1951.

Nehru had insisted that the border between India and China was firm and there was no cause for conflict. Maps were officially published only in 1953-54, showing clear boundaries of India and Tibet, but there were just lines defined by customary use and traditions, not through signed treaties.

China completely denied recognising the McMahon Line – which stretched from Laos to Bhutan due to the Simla Accord of 1914 – saying it was imposed by “imperialists.” However, that was only an excuse; China couldn’t ratify the boundary lines because it implied Tibet was an independent state and China’s occupation was an imperial conquest.

Nehru’s approach towards border control resulted in the loss of opportunities to assert clarity. The Panchsheel Agreement in 1954 gave China a free hand in trade with a minor mention of peaceful coexistence in the preamble.

In 1956, Mao permitted the Dalai Lama to visit India on the occasion of the 2,500 anniversary of Buddha. Nehru had also invited the Chinese Premier Zhou to ensure Mao had no bad business behind his back. When Lama discussed the possibility of seeking asylum, Nehru was determined not to take any step that could rift the India-China relationship.

Nehru seemed to barely pay attention to Lama’s ail until he said it might be better for him not to return. Nehru snapped back to his senses and clearly stated, “But you must realise…that India cannot support you.”

Tensions increased after September 1957, when the construction of Aksai Chin Road was complete. China began occupying and claiming disputed land. The destruction of monasteries in Tibetan populated areas of China sent an influx of refugees not just in central Tibet but even in China.

In March 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India, and the widespread public sympathy urged the government of India to accept the Protector’s asylee status, which irked China. Several border issues took place after that.

In 1958-59, China was going through internal turmoil due to the failure of the Great Leap Forward. Famine followed. Zhou had visited India to discuss the border issues. While Nehru wanted the negotiations to work, the Chinese proposal kept in mind to legitimise the takeover of Tibet, which, now, due to political pressure, was not something Nehru could accept.

It was clear that India was going to stand by Dalai Lama. Concerns regarding the growth of Tibetan activity in India, the inconclusive visits of Zhou in 1960, and the deteriorating relationship resulted in the India-China border conflict of 1962.

After the conflict, India strongly supported Tibetan refugees. They set up “a government-in-exile” in Dharamsala, and India has provided much assistance, such as the allocation of land and funding for schools.

Indian official stance over the matter has remained that India does not encourage the political activity of the refugees in India against China. Still, Dalai Lama is an important figurehead of religion and spirituality and shall stay as long as he pleases.

Since 1962, India’s relationship with China has witnessed many ups and downs. Tibet continues to play an important role in the relationship between India and China.

India has upheld the view of peaceful coexistence that Nehru had envisioned post-Independence. But China’s expansionist activities across the border – claims over Arunachal Pradesh, militarisation and infrastructural development of mainland Tibet, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) ’s unprovoked aggression at Ladakh – remain a persistent threat to India’s security.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]