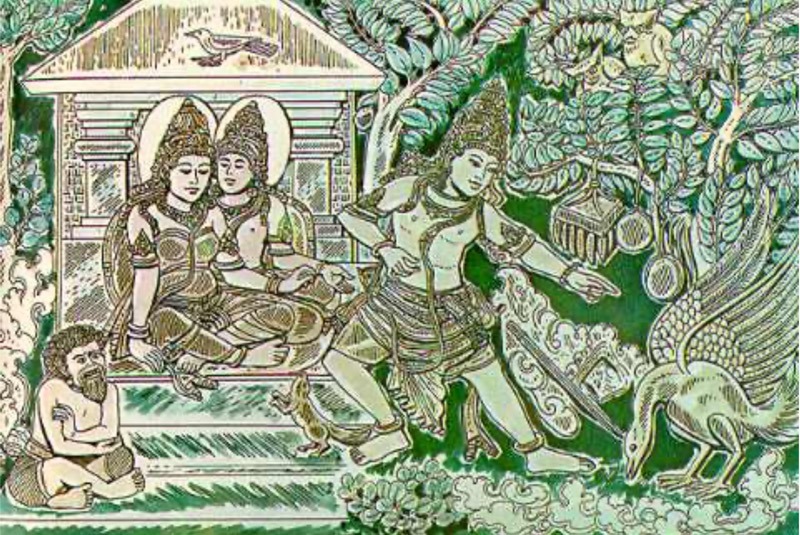

The mention of Java in the Ramayana — when Sugriva sends his search parties to the four corners of the world to find Sita — is not merely poetic geography. It is a glimpse into ancient imagination, where India’s horizons stretched far beyond the subcontinent.

Long before “international relations” became an academic discipline, India’s links with distant lands were living and porous. They were woven through religion, trade, and shared devotion.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]