In early September, in the humid monsoon air of Kerala’s Malappuram district, a fifty-six-year-old woman named Sobhana was brought to the Government Medical College Hospital in Kozhikode. She had fallen ill days earlier, complaining first of headaches, then of confusion and fever. By the time her family rushed her to the hospital, she was already slipping toward unconsciousness. Doctors did what they could, but on Monday, September 8, she died. Hers was not an isolated case. Just two days earlier, a man named Ratheesh, from Wayanad district, succumbed to the same infection. Sobhana became the fifth victim in a month.

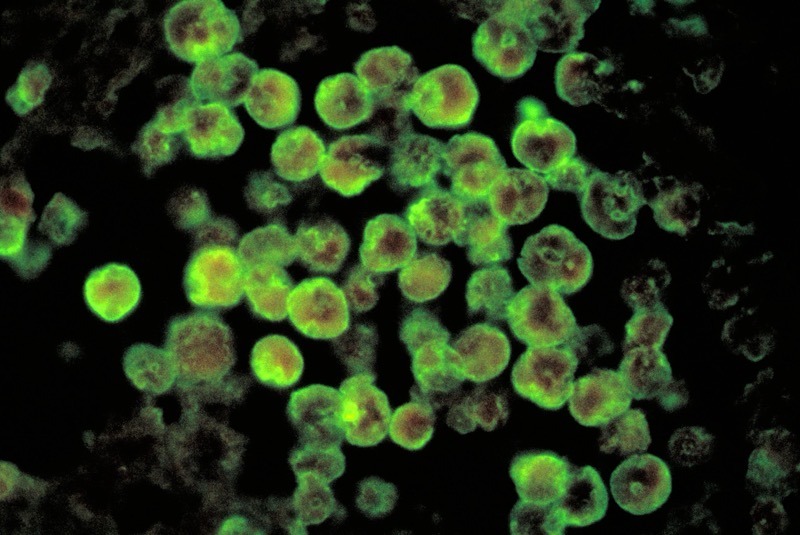

The culprit was not a virus or a bacterium, but something stranger, more unsettling—a single-celled organism called an amoeba, a free-living parasite that thrives in the warm freshwater of lakes, ponds, and rivers. This particular amoeba, Naegleria fowleri, is so rare that most doctors will never see a case in their careers. And yet, when it strikes, the odds of survival are vanishingly slim. The infection it causes—primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, or PAM—is colloquially referred to as “the brain-eating amoeba.” It is a name that sounds sensationalist, the stuff of horror movies, but it is no exaggeration.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]