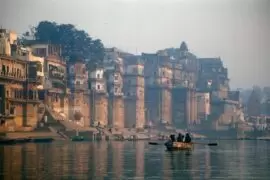

As someone who loves films, I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that cinema is akin to religion in India. I say this also because it’s not uncommon to hear of actors and actresses being referred to as ‘Demi-gods.’ True to their stature, some of them have been deified into gods and goddesses, worshipped with their own temples.

In India, cinema occupies a crest as it continues to entertain, educate, and start a social conversation–be it about poverty and nation-building (as discussed in Mother India), dyslexia (as depicted in Taare Zameen Par) or about the intense pressure young people face in education and career choices (as shown in Three Idiots). Besides, it reflects our insatiable appetite for entertainment and an innate obsession with stories – ‘chutneyfied’ with music, songs, and dance.

Going by the incredible strides Indian cinema has made in the last one hundred years– I think it would be difficult to argue otherwise. Since 1913 – when a printer named Dadasaheb Phalke, inspired by the pictorial life of Jesus Christ, produced India’s first feature film, Raja Harishchandra – Indian cinema has continued to flourish. It has organically progressed in leaps and bounds, despite objections from puritanical propagandists.

That’s because Indian cinema, in a sense, reflects the rambunctious Indian nature – colourful, dramatic, and filled with emotional overtones. As many theorists of Indian cinema point out, they are vehicles that transport the viewer into a ‘fantasy world’ and provide ‘just the right escapism the country needed.’ As the filmmaker Satyajit Ray writes:

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]