Sitting cross-legged in his village home, folk singer Gopal Maurya often opens with a story, bringing to life the loss and longing of millions of forgotten Indian slaves who laboured on plantations and construction sites in British colonies.

And then he sings, retelling the oral histories of poor Indian indentured labourers who were recruited on five-year contracts after Britain abolished slavery in 1833 and shipped to work in the Caribbean, Africa and South East Asia.

“They deceived and took me away,” sings Maurya, who lives in eastern Bihar state, his fingers caressing the harmonium, a type of organ that is popular in India.

“And caged me onto their land,” he sings in a video on YouTube, one of more than 100 songs and photographs uploaded by The Bidesia Project, which aims to conserve Bhojpuri – a language spoken by millions in north and east India – culture.

While many wealthy slave traders have been memorialised with statues, the stories of the men and women they sold are largely unknown. Those tales that have been passed down through oral traditions risk being lost in the modern world.

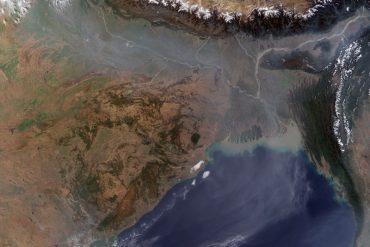

Based on archives and research, the Bidesia Project estimates that 2 million Indians worked as indentured labourers, fleeing poverty and famine at home in the 19th century.

They were exploited and overworked, received little medical care and had no way to return home.

India’s indentured history, as narrated through Bhojpuri songs, is told in a new documentary film, “In Search Of Bidesia,” which premiered at the Dhaka International Film festival this year, and through the growing digital archive.

Bidesia loosely translates as someone who has travelled abroad and is also a genre in Bhojpuri folk music that deals with migration.

“In school, the history we learn is only about our freedom struggle and there is no mention of indenture slavery in our books,” said Simit Bhagat, who directed the documentary, which led him to set up the project to promote Bhojpuri folk culture.

“The history captured in these songs is unfortunate but that is not a reason to forget about them … these songs were written by people who also wanted their journeys to be remembered,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

‘Separation’ Songs

Bhagat’s journey to capture these ‘separation’ songs, a genre that emerged with the rise of indentured labour, began with a bike trip in 2017 across Uttar Pradesh and Bihar states, which have a history of such migration.

He met with some of the last living Bidesia musicians who sang for him and regaled him with stories about men and women separated from their families, working in a foreign land and pining to return home.

“The songs describe how recruiters painted a rosy picture about a better life, more wages and riches and how people were deceived,” Bhagat said.

“The songs reflect the loneliness of workers, the sadness of the women they left behind and how music was like a balm at the end of a long day at work.”

The musicians’ desire to ensure these songs of love and longing do not slip into oblivion led to the documentary and founding of The Bidesia Project.

Bhagat has already recorded 150 songs and is tuning into more. His 1,200 km (746 mile) journey so far has given him a rare insight into their history.

“An elderly woman I met and recorded said she had learnt the songs from her mother,” Bhagat said.

“She was in her nineties and her voice was still strong and so unique. I hear she is a bit unwell now and feel lucky that I was able to record her singing.”

Past & Present

Bhagat’s twin projects have tapped into renewed global interest in racism and colonial history, following the death of African-American George Floyd after he was knelt on by a white police officer.

As protesters have toppled monuments honoring British slave owners and U.S. Confederate leaders who defended slavery, India’s anti-racism debate has focused on caste discrimination – both in the past and in the present.

Lower-caste Dalits have called on other Indians to acknowledge the centuries of oppression, violence and segregation they have endured at the bottom of the ancient caste hierarchy, whose membership was determined at birth.

Historically, they were barred from even having their shadows touch those of people from higher castes. But Bhagat came across descriptions of boat journeys where rigid caste hierarchies were broken with people being herded as cattle.

“They told us Trinidad was only six hours away by ship. But it took us 103 days to reach. Many died onboard. I cried and cried. By now, I was almost a slave,” read one archival testimony in the film.

Bhagat said the songs are encouraging people to examine their history more closely and embrace their past, with some people of Indian heritage now choosing to add the derogatory term for indentured workers “girmit” to their names.

Many families have told Bhagat that his work has helped them to answer a lot of questions about the traditions they follow but did not understand and to learn more about their ancestors.

“When I listen to this I can feel the pain that my great grandparents went through,” Tanuja Dunpath from South Africa wrote on The Bidesia Project’s YouTube page after listening to one of the songs.

For Bhagat, who as a child often wondered why many West Indian cricketers had Indian names, the folk songs have spotlighted a part of history that he wishes to keep alive.

“Their relevance couldn’t be more in today’s times when people are looking for answers to questions of race, inequality and discrimination,” Bhagat said, who also interviewed families of indentured workers.

“Today people want to embrace the struggle of their ancestors, their roots and their identity. The songs are a place to start for many.”

*This story was first published in Thomson Reuters News Foundation.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]