American women are very beautiful…even the prettiest woman of our country will look like a black owl there.

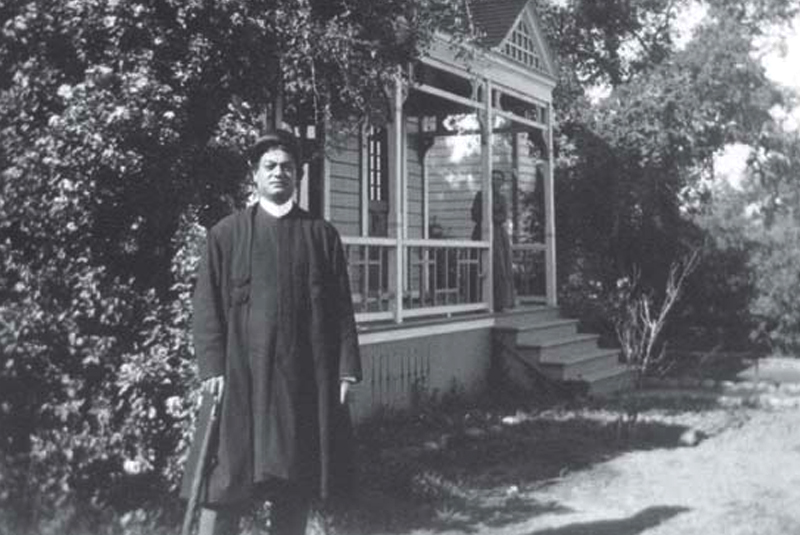

When Narendranath Datta, alias Swami Vivekanand, toured the United States in 1893, he conducted several public and private lectures and classes. He spent many years there, was well-received, and gained popularity, especially among Western women.

Datta charmed and mystified American and English women with his ‘attractive aura, deep baritone, colourful silk robe and turban, and sweet chanting in exotic Sanskrit.’ Slightly more than five feet eight inches tall, ‘plump, and cherubic, to ladies, the thirty-year-old monk seemed not only tall and magnificent but also enigmatic and holy.’

Despite Datta’s enormous popularity with American women, his attitude towards them, and femininity in general, was demeaning, even disdainful. Given his larger-than-life image, people usually disregard the undercurrent of gender prejudice that lurks beneath his sermons, lectures and remarks.

When the young monk came to the United States, women were enchanted by his presence. Christina Greenstidel, a New York woman who met Datta in Detroit, saw him as a ‘powerful saint’ full of ‘ojas.’ He exuded, she wrote, a ‘mysterious power which comes when the physical forces of the body are transmuted into spiritual power.’ Some American women who met Datta also gave similar testimonies.

At first, Datta was overwhelmed with the adoration he received from American women. However, he soon began to dread it as it caused suspicion and paranoia of eroticism. At the time, he believed ‘female sexuality was the greatest danger to male continence.’

Evidence indicates that the Datta was frightened even by the adoration and love he received from his female students. So, Vivekananda recommended ‘de-sexualizing’ women by elevating them to the role of mothers.

“[I]n many texts, women are idealized as pure, spiritual, and nurturant when they are de-erotized and placed in clearly defined and sexually tabooed blood relationships such as those of mother, sister, or daughter. In other words, when emphasis is placed on their sexuality, they are often vilified for this aspect of their nature and condemned as temptress, seductress, or whore.”

Dutta was also a product of a culture that was ‘heavily obsessed with fair skin.’ His letters reveal that he was initially charmed by fair-skinned women. In a ‘strictly confidential’ but ‘disarmingly candid’ letter to a friend, Dutta thought American women were so beautiful that the women from India, no matter how attractive, would look like a ‘black owl.’

Despite his cringeworthy comments on American women, his denigration of Indian women, and his patriarchal ideas, he was often venerated and portrayed as a larger-than-life image.

Letters from Dutta also show judgemental and demeaning comments made by him that portray his emotional conflict in his views regarding Western women. For example, he had called the American ladies ‘pure as the icicle on Diana’s temple,’ but he changed his mind and regarded them as excessively materialistic with no spirituality.

He claimed Christian women sought luxuries and recreation, such as wealth, social power, operas, novels, etc. and told his pupil, Saracchandra Chakrabarti, that attending his lectures sexually excited American ‘sluts’ and ‘buggers.’ He labelled the ladies who followed him in Boston as ‘all faddists, all fickle, merely bent on following something new and strange.’

Datta demonstrated that, for him, the idea of a woman fluctuates between maternal and carnal extremes. He believed that cultivating purity of mind was dependent on virginity. Unsurprisingly, Swami’s favourite ideals were Sita, who voluntarily endured every test of fidelity, and Savitri, whose unwavering love ostensibly brought her dead husband back to life. In his words, ‘the ideal womanhood of India is motherhood—that marvellous, unselfish, all suffering, ever-forgiving mother.’

Several times, during his life and work, Vivekananda cautioned men against dictating the direction or speed of women’s reform, saying that this should be left to the women themselves. While this contains aspects of feminism, Swami was likely cautioning ardent male reformers against overreaching on such a sensitive subject. In his words:

No man shall dictate to a woman nor women to a man… Women will work out their destiny better than men can ever do for them. All mischief has come because men undertook to shape the destiny of women.

For Datta, education was the most essential step toward women’s emancipation. However, he also advocated for a particular kind of education based on what he defined as ‘true womanhood,’ that is, ‘women fit to be mothers of heroes.’

Explaining the essence of true womanhood, Sister Nivedita, his most celebrated student, wrote: ‘the old-time intensity of trustful and devoted companionship to the husband.’

Like many Hindu reformists of nineteenth-century India, Datta had much to say about the women of the country. His words, although calling for self-reliance and education, were not empowering. They were somewhat degrading and supportive of society’s limiting patriarchal bounds.

His discourse on women was marked by conflict and ambiguity. It undermined the very goal of real change or reform. His discourse promoted female education while denying educated women the freedom to live independently. By putting them in the pigeonhole of a ‘mother’ or ‘sister,’ the women were merely reduced to an apparatus to produce great men and placed them right under the control of men.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]