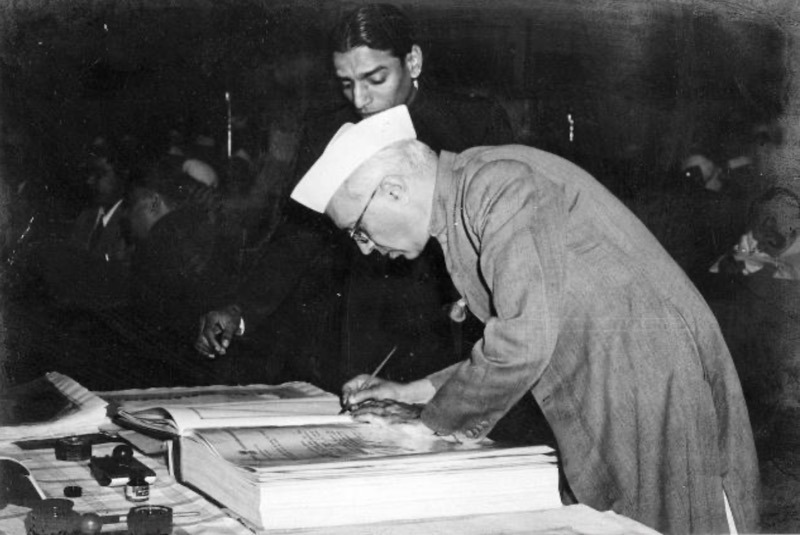

In an age where the rise of superstition and political patronage for religious clerics has become disturbingly commonplace, it is painful to admit that the lofty ideals of scientific temper espoused by Jawaharlal Nehru seem increasingly distant from the realities of contemporary India. The gap between the Nehruvian vision of a rational, scientific approach to life and the prevailing forces of irrationality has never seemed so wide.

Nehru remains as relevant today as he was in the mid-20th century, a time when science and rationality were poised to shape India’s destiny. In 1947, he set India on a course toward modernity rooted in scientific thinking, firmly believing that “only science can solve the problem of hunger and poverty,” and that it was science alone that could eradicate the backwardness plaguing the country.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]