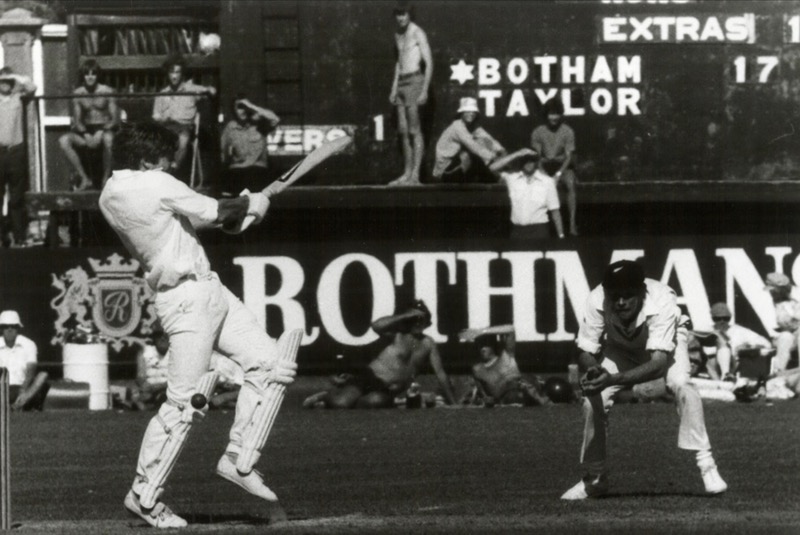

Sir Ian Botham. The name’s the high-maiden of cricket — an epiphenomenon of classicism and the abstract. Of varied alternatives for every situation.

Botham’s identity was such that it always shone, what with the great man’s several zones of potentialities. It also filled in the slots between what was done; at others, of what might be done. A stupendous all-rounder, Botham celebrated something of a ‘skewed philosopher’ in his game — not by his antics. For one simple reason. Each moment, for him, was not only a new experience, but also an intellectual ‘delusion.’

Botham was never a behaviourist. He was also no Francis Bacon. He never demanded a thorough elicitation of cause and effect in cricketing action. Yet, his cricket was scientific. Obvious. Apparent. But, nothing beneath science, nor above it. The distinction between his eccentricity and cricketing pyrotechnics was also fundamental. He may, or may not, have accepted happily the theology of the Sermon on the Mount, but this, in no way, prevented him from smoking pot, or indulging in brawls.

Botham was a cricketer with a cause. Take, for instance, his several trysts for charity and the gutsy manner in which he quit Somerset in protest, after the county sacked his close pal, Sir Viv Richards (and, Joel Garner), in 1986. Come 1988, Botham embarked on a 500-mile hike extending from Perpignan in France to Turin in Italy, accompanied by three elephants a la Hannibal. The outcome? He was able to raise UK£1 million for leukaemia research. At the same time, Botham never fancied touring the subcontinent — a place, he often said, as being best suited to sending one’s mother-in-law to.

The Next Sobers?

Born in Hesall, on November 24, 1955, Botham made his Test debut against old foes, Australia, at Nottingham, on July 28, 1977. Standing six-foot, one-inch tall, Botham was a ‘hit,’ post-haste. It was a dream fulfilled. As a boy, he had dreamt of becoming the next Sobers. “He (Gary) was my one big hero.” Years later, Botham seemed to have achieved enough to realise his dream — the difference being of degree. That apart, Botham was a good centre-forward, and indulged in a host of exploits outside of cricket.

Botham, at his peak, was more than one man: a three-in-one genius. He could pile up a breezy 50 within no time. As a bowler, with a bounding run-up, he was a demon with the red cherry. As a fielder, he was a tiger on the prowl. However, Botham, in spite of his phenomenal abilities, never did flower into a brilliant leader of men. He proved to be a big flop, as captain, during England’s tour of the Caribbean, in 1981. He was a man in a hurry.

As the legendary Sir Geoffrey Boycott observed, “Botham should have been encouraged to take a longer view. He should have been groomed for three or four years longer: that would have been in his best interests and in the best interests of English cricket. Had Botham been given, say, four years without responsibility of captaincy, he would have been in command of his game and of himself, and ready, as (Richie) Benaud was, to fulfil himself as a player and as captain.” Perfect logic.

The Match-Winner

Not for nothing was Botham nicknamed, ‘Guy, the Gorilla,’ or ‘Beefy.’ In his mood, he was a match-winner. He could win matches from the depths of despair. Was he the greatest all-rounder of all time? Over to Sir Garfield Sobers, “Would Botham have taken so many wickets if he was playing regularly against (Sir Everton) Weekes, (Sir Frank) Worrell, (Sir Clyde) Walcott, and the other great players of my time? I doubt it. Ian could have stamped himself as one of the greatest all-rounders very early in his career if his batting had been more responsible. He wanted to play his shots too early. You cannot slog good bowling, particularly the West Indian bowling. Even the best players have to graft and build an innings.”

Over to Sobers, again, “(Keith) Miller was a better all-rounder than Ian because he had more style. He was a faster, more threatening bowler. And, (Sir Richard) Hadlee is a thinking bowler. He has taken wickets against the best batsmen on their own pitches. He has proved himself. When Botham toured the West Indies in 1985-86, he took 11 wickets at 48 apiece. I judge true greatness on the quality of the opposition.”

All the same, Botham, on his day, never did anything by halves. Wrote David Gower, the Golden Boy of English cricket, “He (Botham) takes his soccer and golf seriously. The same with his flying. He has a competition, killer-instinct that makes everything he does a challenge, a drive that is reinforced by colossal reserves of energy. He can do nothing on a small scale.”

Yes, Botham did not do anything on a small scale. Here’s proof: 102 Tests, 161 innings, six times not out, 5,200 runs, 14 hundreds, 22 fifties, highest score 208; average 33.54. Bowling: 383 wickets; average 28.40; catches 120. Forget the stats, Botham’s one-day record wasn’t bad either. For someone who was transformed into a bludgeon of an all-rounder, by Mike Brearley, a shrewd cricketing brain, and great captain, Botham was, doubtless, the toast of an entire generation.

That metaphor will remain. In frame. In film. In print. And, on the Web.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to editor@madrascourier.com