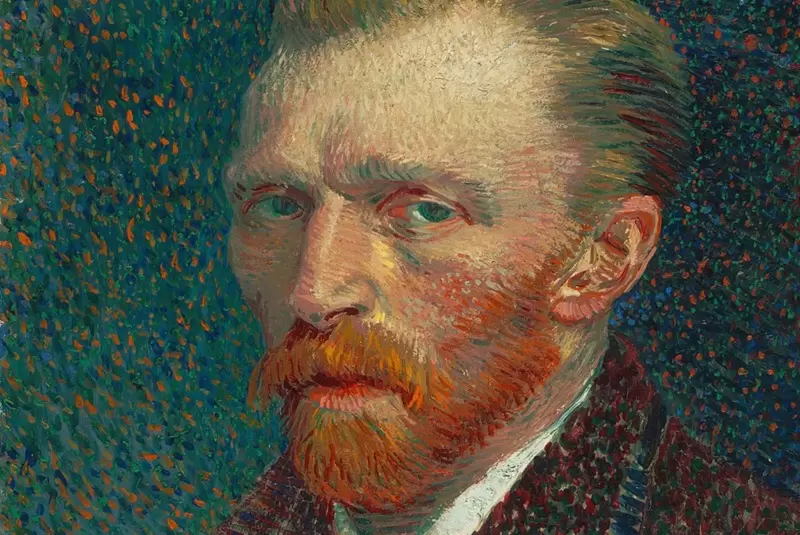

In an era where art is often consumed as a form of entertainment, an immersive exhibition of Van Gogh’s paintings has become the latest craze. The galleries, equipped with pulsating lights and resounding music, aim to transport visitors into the very world of Vincent Van Gogh, allowing them to experience his most famous works as if they were stepping inside them. Over 100 of these ‘immersive Van Gogh’ experiences have opened across the United States alone, drawing crowds eager to see his paintings in a new light. Yet, as the phenomenon grows, one can’t help but wonder: would Van Gogh, had he lived to see his legacy in such an extravagant commercial light, have been flabbergasted by the sheer scale of his posthumous fame?

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]