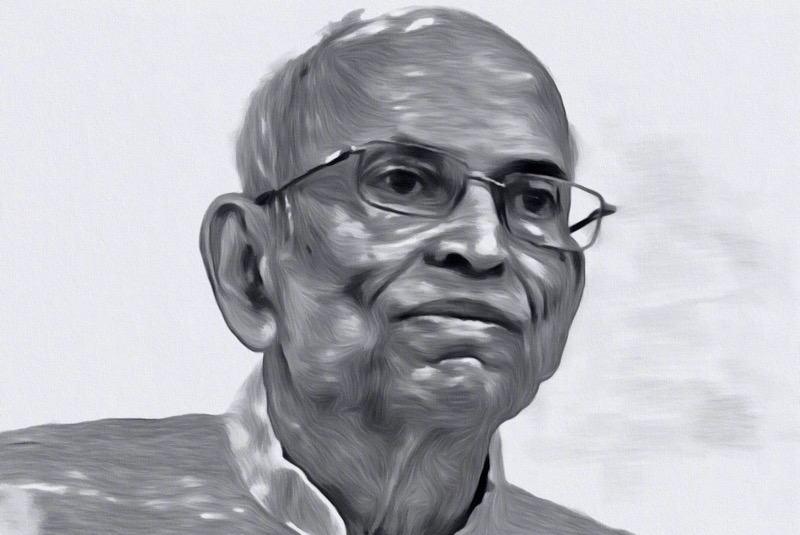

I met Madhav Gadgil about a decade ago in Delhi, on the margins of a conference that had little to do with forests or rivers. The conversation deviated, as it always did with him, towards Kerala. He spoke of the Western Ghats, emotionally, as a living presence, recalling the sharpness of early environmental debates in the state, the courage of activists, the memory of Silent Valley, and the stubborn hope that people would one day listen before the hills spoke back. There was hardly any bitterness in his voice. There was only a silent insistence that knowledge, when ignored, does not disappear. It waits.

That trait explained his life’s mission. Gadgil never believed ecology belonged only to laboratories or expert committees. For him, it lived in villages, forests, coasts, and everyday choices. He trusted people more than institutions, and evidence more than authority. That trust made him admired, contested, and, in Kerala, unforgettable.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]