In the lush and storied land of North Malabar, once folded into the cartography of the Madras Presidency, the coastal towns of Kannur, Tellicherry, Mahe, Dharmadam, and Vadagara pulsed with the rhythms of trade winds and the slow churn of history. It was here that the Thiyas, a matrilineal community, quietly nurtured generations of women who seemed at once deeply rooted in tradition yet ahead of their time. While colonial and princely India largely imagined women as secondary—cloistered, ornamental, dependent—these women of Malabar were charting another path, their lives infused with a dignity and autonomy that puzzled outsiders yet seemed entirely natural to them.

Marriage itself took on a form that confounded the prevailing norms. A Thiya wedding, until not too many generations ago, was orchestrated not by the bride’s people but by the groom’s family. There was no exchange of dowry, no parade of trunks laden with silks, brass lamps, or carved furniture. Instead, the groom’s family gathered the trousseau, and his sister or aunt procured sarees, blouses, underskirts, and even undergarments—an unspoken gesture of solidarity between women across households. The gold tali chain, too, came from the groom’s side, and the only wealth the bride carried was the jewellery she wore on her wedding day. Yet she did not enter her new life impoverished, for her maternal home remained her anchor, the enduring source of both emotional and material support.

Education was not merely encouraged but regarded as essential. In this community, there was no bifurcation between sons and daughters in their schooling. My great-grandmother, improbably modern for her times, attended a French convent in Mahe in the 1880s. Another ancestor, equally resolute, went to the Sacred Heart’s Convent in Tellicherry, making her daily pilgrimage to school in a jutka vandi, its wheels rattling against red laterite roads. My grandmother Leela, who wrote in English with a grace and precision that could rival professional scribes, left behind delicate blue inland letters addressed to me when I lived in the Assistant Commissioner’s residence in Ranikhet.

Those letters still survive, paper ghosts whispering across time. Her coconut toffee recipe—soft, pale pink, tinged with cochineal—remains etched in memory, just as much a part of her legacy as the upright bookstand, the card table, and the long reclining chairs of our ancestral home in Calicut. As children, we consumed not only kilos of banana chips but also her carefully inked letters, a form of nourishment as important as food itself.

Among my father’s aunts, education blossomed into eccentric brilliance. Janaki Ammal, the renowned cytogeneticist, once confessed in her journal that she read each of Shakespeare’s plays twice in order to fully absorb them, her appetite for literature as methodical as her science. Another aunt, Sumitra, offered in her diary a confession both tender and defiant: “I am suffering from womb pain. I just want to lie in bed and read.” When the British decreed English proficiency as a requirement for government service in North Malabar, it was the Thiyas—unencumbered by caste pride in Sanskrit or Malayalam—who seized the colonial tongue most swiftly, transforming it into a tool of aspiration. Letters to our educated aunts were invariably addressed with degrees appended: Miss V. Radha, B.A., for learning itself was a form of adornment.

The sense of practicality that defined these women extended even into the rituals of death. My grandmother, with characteristic clarity, declared she wished not to be cremated but buried beneath the Malgova mango tree in our compound. “Let my body be of some use,” she said, her words a premonition of sustainability before the word entered common parlance. In that gesture of becoming nourishment for the earth, she enacted a philosophy that lay dormant in the soil of Malabar, where mango groves and coconut palms held the wisdom of centuries.

Childhood summers unfolded like endless myths in Dharmadam, where six of us girl cousins would gather at Onaparambth, our ancestral house shaded by mangoes, jackfruit, and pepper vines. The Arabian Sea was a ten-minute walk away, its briny invitation irresistible. We crossed to Thiruti island during low tide, scribbling “Parashurama, you lost!” in the sand, our rebellion against myth washed clean by returning waves. Evenings were spent on the verandah, where Aunt Radha, silhouetted against the bleeding colours of the sunset, watched us with indulgent silence, as though she too understood that small acts of defiance carried their own kind of holiness.

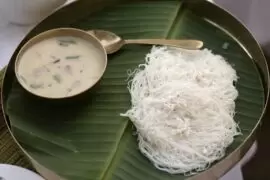

The cuisine of the Thiyas, curiously absent from Kerala’s celebrated culinary pantheon, was a mosaic of flavours both inventive and ancient. My grand-aunt Sunanda made unnakai—ripe nendra bananas filled with coconut, raisins, cashews, and cardamom, fried to golden perfection—that perfumed the air with sweetness. Kinnathappam, spiced with fennel and shallots, and ulava kanni, a fenugreek payasam thickened with jaggery and coconut milk, occupied places of reverence.

Serrated gooseberries plucked from our compound were simmered into a jam of wine-red brilliance, spread onto bakery-fresh bread in an act that fused the rustic with the urbane. Fish remained at the centre of our meals, whether as fried oysters spiced with shallots and pepper for breakfast, or fish curry soured with vilumbi fruit, its tartness our version of sambhar. Even today, my Canadian son-in-law requests it on every visit, as though the dish were a bridge between continents. And always, in the background, there was Patanjali, the house help, grinding coconut, chilli, and turmeric on stone slabs, her rhythmic pounding echoing across decades, a music of sustenance.

Memory, in my family, often arrives flavoured with mussels. My grandmother’s mussel pickle, packed into jars I smuggled into hostel rooms, transformed bland rice into a feast. Aunt Thangam, who passed only last year, could conjure arikadaka—mussels steamed and fried in rice batter—for tea with a magician’s flourish. A pilgrimage to Kannur took us once to the famed Parassinikadavu Muthappan temple on the Valapattanam river, where Theyyam dancers embody the deity, listening to the troubles of devotees and offering counsel. Here, caste dissolves, dogs are fed as sacred beings, and the boundaries between the human and the divine blur in the firelit ritual.

The brilliance of these women lay not merely in their education or culinary talent but in the richness of their inner lives. Even now, Aunt Sitala, at ninety, embroiders tirelessly for charity, each stitch a testament to patience. Girija paints flowers with devotion that borders on prayer. Uma aunty, trailblazing in her own way, became one of Tamil Nadu’s most beloved tourist guides, her voice carrying the grandeur of Chola temples and the intimacy of untold stories. When my husband’s centenarian aunt from New York visited, she declared Uma to be the finest guide she had ever met. Watching them converse, two nonagenarians exchanging admiration, was like watching history unfold.

None of this would have been possible without the men who, instead of gatekeeping, opened doors. My father, a Brigadier in the Indian Army, gave my sister and me a childhood that was both disciplined and untamed: fishing expeditions, camping trips, pets of all varieties, and rum bottles smuggled into the JNU hostel for our not-yet-husbands. His only advice on marriage was disarmingly simple: “Find someone who will take care of you and enjoy a drink with me.”

When my sister married a Punjabi, his only concern was whether the man could indeed care for her, caste or region be damned. Our cousins, who lost their mother when they were too young, were raised by grandparents who taught them to swim in the kollam’s waters, shoot at bullseyes, tend trees, and even clean their grandfather’s guns. Reverence was reserved not for patriarchal authority but for the sarpakavu, the sacred snake grove in our compound. It tended with a spirituality that was as ecological as it was religious.

For me, identity has always been both rooted and itinerant. I am deeply Malayali, yet my life has traversed the map of India, from the Kashmir valley to the Nilgiris, Madras to Delhi, Ranikhet to Uttar Pradesh. Now, in Chennai, in what feel like the sunset years, I find myself reflecting on a worldview shaped not by political manifestos or sweeping revolutions, but by mango trees and mussel pickles, midnight card games and Shakespeare read in bed, embroidery circles and fish curry mornings, laughter that was as untamed as the sea. It is a worldview shaped by women—not loud revolutionaries, but quiet architects of freedom—who stitched independence into the fabric of daily life until it became indistinguishable from existence itself.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]