Twice in quick succession, the soothsayers of electoral politics have been proven wrong. Their electoral prophesies — belied by the results of the recent general election as well as the Haryana (and to some extent, the Maharashtra) assembly election — have jousted for piecing together statistical explanations as to why their ‘scientific predictions’ did not square up with the way things panned out. Like an unrelenting prophesy-maker, they insist that their methods are scientific and akin to the law of gravitation, their equations cannot fail.

“Perhaps some key statistical variable was not factored in,” they say. “Perhaps there was some flaw in the application of the formulae.” “Or the data relied upon was deficient in some way.” They skirt around the inherent contradictions of their so-called “science,” insisting that their methods and epistemology are scientific and would yield correct results if correctly applied.

They defend psephology by the methods of psephology itself, i.e. arithmetic and statistics — as if they can heal an ailment with the ailment itself. In their quest, they resemble the child who kicks up the dust and then complains that he cannot see.

The vanities of their scientific method make them usurp the role of an omniscient observer who can peer into the voter’s mind when alone in the polling booth with just her conscience.

They forget that the scientific method has boundaries, which, when transgressed, morph science into ‘scientism.’ Science ceases to be science—a method of knowledge—and instead becomes ‘scientism’—an ideology.

Scientism assumes that the fundamental premises of natural science, i.e., cause-and-effect, empirical reason, and reproducibility, can be applied to domains beyond the physical realm. It thrusts its weight on dogmatic adherence to the methods of science and assumes that the same method can be equally applied to study both matter and mind. Thus, it inflates the boundaries of science and makes it assume the proportions of an all-permeating ideology.

While the soothsayers of electoral politics claim to be pursuing a science, unbeknown to them, they are ideologically afflicted with scientism. For them, men and particles are alike, and both must be dictated by similar empirical laws of reason and causation. They objectify the voters, denuding them of their subjectivity, free will, and volitions and restrain them into pre-determined laws of statistics and behaviourism as if they are the proverbial Newtonian apples that inevitably follow the laws of mechanics.

These soothsayers forget that science as an idea can work wonders; however, scientism as an ideology blinds and absolute ideology blinds absolutely. In their blindness, they fail to realise that the voters whose conscience they objectify are not physical objects but human subjects with free will and an inalienable subjecthood. All their prophesies betray their presumptuousness:

· “Voters in assembly elections will swing ten per cent away from the party they voted for in the general election as they have done so in the past two elections.”

· “Sixty per cent voters of this particular caste shall vote for this candidate.”

· “Voters will punish the candidates they have voted for in the previous municipal elections as they have shown this trend the past couple of decades.”

Such prophesies, bearing a cosmetic resemblance to the laws of natural sciences, are based on a singular premise: the voter must be alienated from her subjecthood. The dehumanising determinism of psephology straight jackets the individual subject into geometries of empirical reason, arithmetic, and the laws of mechanical statistics, leaving no scope for individual subjectivity, volitions, emotionality, and, above all, idiosyncrasies.

The hubris of scientism is not simply restricted to psephology; psephology has inherited it from other positivistic social sciences. The history goes back a couple of centuries when, in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, Europe was swayed by the omnipotence of science.

Science was seen as all-powerful, and the method of science was seen as all-knowing. Professors and philosophers were split as to whether the evolving disciplines of sociology, politics, economics, etc. should be categorised as “humanities” or “social sciences.”

The academic debate between two philosophers — Auguste Comte and Wilhelm Dilthey — is a metaphor for the dilemma of splitting the academic world. Inspired by the age of scientific reason and drawing from the offshoots of Cartesian rationalism, Comte intended to imbue these disciplines with scientific certainty. At the same time, Dilthey was a votary of preserving the amorphous uncertainties of human subjectivities. Perhaps the intellectual climate of that age favoured Comte, and “humanities” took a positivistic turn to become “social sciences.”

Psephology is the youngest progeny of these positivistic social sciences. Like other positivistic social sciences, it employs scientific epistemology to study human nature. Whenever it runs into contradictions, instead of blaming them on their roots, it attempts to find a ‘scientific solution’ to its non-scientific problems. To cure its disease, it harps on the pathogen that caused the disease and thus runs into self-defeating loops of circularity.

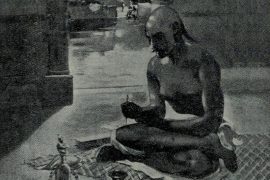

When one looks at the vanities of this over-zealous ‘science’, one is drawn to the wisdom of the sage-philosopher, Tolstoy:

If we admit that human life can be ruled by reason, the possibility of life is destroyed.”

While ideating War and Peace, Tolstoy assumed the role of a cosmic observer, observing the Napoleonic invasion of Russia from a celestial pedestal. He observes the humanity coalescing into an army, the rise of a leader called Napoleon and the war-like movement of this humanity under Napoleon from the far west in Paris to the far east in Moscow. Then, he observes its retreat from Moscow to Paris, chased away by the Russian forces led by Tsar Alexander-1 and the subsequent fall of Napoleon. As a sage-philosopher, Tolstoy burns with two philosophical queries:

· “What forces move humanity – oscillating from the far-west to far-east and reverse?”

· “What causes these events in history?”

The questions that simmered in Tolstoy are akin to the questions that psephological-scientism pretends to answer:

· “What forces move the masses of voters?”

· “What causes these major events in the electoral and democratic history of a nation?”

The sage-philosopher does not consign these philosophical queries to easy statistical solutions. Instead, he reprimands the hubris of scientism that reduces philosophical meditations to arithmetic equations.

In the epilogue to War and Peace, he answers that the forces that move humanity are “mysterious” and their laws of motion are unknown and unknowable. No causal explanation can do justice to these questions, just like no statistics can do justice to the questions that psephologists pretend to answer.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]