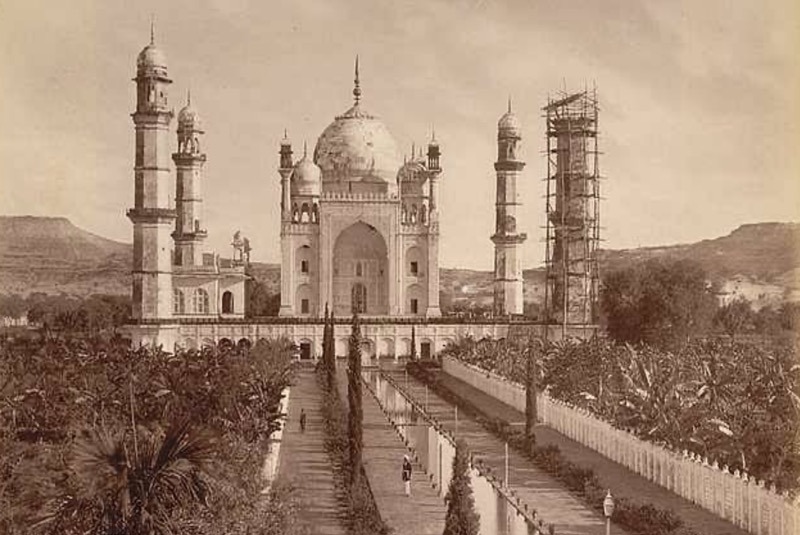

In the desolate stretch of the Deccan Plateau, amid the arid lands that once cradled the heart of the Mughal Empire, the city of Aurangabad stands as a stubborn echo of a dynasty’s contradictions. It is a city born of a ruler’s ambition, where the past, rich with palatial grandeur and meticulous artistry, collides with the quiet austerity of a reign determined to defy it. Here, in the midst of a parched landscape, lies the Bibi Ka Maqbara, a tomb that has, for centuries, been the silent witness to a story of love, loss, and the fraying edges of imperial opulence.

Aurangzeb, the last of the great Mughal emperors, ascended the throne on 31 July 1658. Unlike his predecessors, whose lavish patronage of art and architecture had given rise to monumental structures like the Taj Mahal, Aurangzeb’s rule was marked by a stark asceticism. His reign, characterised by puritanical views on governance and culture, contrasted sharply with the excesses of Shah Jahan and his other forebears, whose palaces and public works were defined by luxury and extravagance.

Aurangzeb’s lifestyle, built on simplicity and discipline, was legendary; he reportedly spent his days copying the Quran and weaving skullcaps, activities that marked his devout approach to life. To him, the lavish expenditures on architecture and art that had flourished under the Mughal emperors seemed not just unnecessary but a form of moral decay.

Yet, like many emperors before him, Aurangzeb could not entirely escape the weight of his lineage, nor the expectations that came with his imperial inheritance. His first wife, Dilras Banu Begum, had borne him five children, including the eldest, Muhammad Azam Shah.

When Dilras Banu died after a prolonged illness on 8 October 1657, Aurangzeb’s grief led him, for once, to set aside his austere principles. Unable to let go of the idea of commemorating his beloved wife in the way that his father had memorialised his own queen, Aurangzeb did what, to him, might have seemed both a personal indulgence and a political necessity: he ordered the construction of a grand mausoleum in her honour. This tomb, however, would not be a replica of the Taj Mahal, that dazzling symbol of love and empire. Aurangzeb’s frugality would impose strict limits on its design.

He gave the task of creating the mausoleum to Attaullah Rashidi, the son of Ustad Ahmad Lahori, the architect behind the Taj Mahal. Having spent years under his father’s tutelage, Attaullah was deeply familiar with the intricacies of Mughal architecture, particularly the blending of Persian and Indian styles. His hands had shaped the marble that glistened at Agra, and now, his touch would be felt in Aurangabad. But the conditions were different here.

While the Taj Mahal was built on an unprecedented scale, lavish in its cost and materials, Aurangzeb’s mausoleum was bound by tight financial constraints. He allocated a mere 700,000 rupees for the project, a sum that paled in comparison to the Taj’s astronomical expenses.

Despite the budgetary limits, Attaullah Rashidi and his team—including the material expert Hanspat Rai—set out to create a tomb that would still reflect the splendour of the Mughal Empire, albeit on a smaller scale. The site they chose was away from the bustling centre of Aurangabad, in a tranquil area that would allow the monument to stand as a sanctuary of peace.

They brought marble from the distant mines of Jaipur, a monumental task that, according to the French merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, required hundreds of oxen-drawn carts to transport it. The tomb would feature all the elements of Mughal architecture: minarets, a dome, and intricately designed lattice windows, familiar to anyone who had seen the Taj Mahal or its architectural cousins across India. Yet, the lack of funds meant that the final result was not a direct imitation, but a modest, scaled-back homage to the great tombs of the Mughal era.

The completed mausoleum, which came to be known as Bibi Ka Maqbara, was a structure that spoke of love as much as it did of restraint. It was, in its own way, a testament to Aurangzeb’s enduring devotion to his first wife, one that outlasted his own personal beliefs. While the grand marble expanse of the Taj Mahal might have outshone it, Bibi Ka Maqbara carried its own quiet elegance, a reminder that not all legacies are built on opulence and excess. Some, instead, are born from sacrifice and remembrance.

However, the story of Bibi Ka Maqbara was not just about architecture; it was also a reflection of the empire’s changing political and social landscape. Aurangzeb’s decision to move away from the lavishness of his ancestors was not merely a matter of personal preference. It was, in part, a calculated effort to distance himself from the indulgent elements of Mughal rule, which he believed had contributed to the empire’s decline.

His asceticism was, therefore, not merely a personal disposition but a political statement: he sought to return the empire to what he saw as its austere and religiously orthodox roots. Yet, even as he distanced himself from the grandeur of his forebears, he could not entirely escape the legacy that they had created. Architecture, art, and the deeply embedded Mughal traditions continued to shape the empire, even as the emperor’s personal policies sought to curtail them.

The tomb became an instant landmark, not only for its beautiful design but also for its historical significance. It was the largest structure that Aurangzeb could claim in terms of architectural achievement, and it served as the most visible symbol of his reign’s contradictory nature.

After all, it was both a monument to love and a reflection of the emperor’s strained relationship with the excesses that had defined the Mughal dynasty. Bibi Ka Maqbara stands today as a testament to the complexities of Aurangzeb’s rule, a ruler who sought to erase the grandeur of his ancestors while still upholding their legacy in ways he could not entirely suppress.

In the years following its construction, Aurangzeb’s personal connection to the tomb deepened. Though he had overseen its creation, he would not be buried there. Instead, he chose a much simpler resting place for himself, a few kilometres away in Khuldabad, a town that had long been associated with Muslim saints.

He was interred with minimal ceremony, his grave unadorned, a stark contrast to the opulent tombs of his ancestors. It was as though Aurangzeb had made peace with his own legacy, recognising that some things—like the need for expression through grand monuments—could not be easily suppressed, even by the most rigid of rulers.

Ironically, the austerity of his reign perhaps ensured the survival of his legacy, even if it was not in the way he had intended. Bibi Ka Maqbara stands as a monument that reflects the emperor’s love for his wife and as a reminder of the dynastic forces that shaped the Mughal Empire.

While Aurangzeb may have sought to distance himself from the past, he inadvertently ensured that the architectural legacy of the Mughals would continue to captivate the world. The tomb’s graceful proportions, delicate interplay of marble and sunlight, and serene yet sombre presence inspire awe— a testament to the fact that the Mughal legacy could never truly be erased.

In the centuries since, Bibi Ka Maqbara has stood not only as a symbol of the Mughal dynasty’s fading influence but also as a silent witness to the shifting sands of Indian history. Its marble façade, weathered by time, continues to attract visitors from all over the world—drawn not only by its beauty but by the story it tells of an emperor who, despite his attempts to curtail the excesses of his lineage, could not entirely escape the pull of love. The mausoleum endures, a fragile echo of a dynasty that, like the empire itself, had its own moments of brilliance—and moments of restraint—but never ceased to speak to the eternal human condition.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]