Science is continuously helping improve human existence. Technology we could only imagine about a decade ago is now a reality. During COVID-19, we have seen the difficulties that healthcare systems have encountered in combating disease and preserving human lives.

Recently, scientists found a way to help a person with severe paralysis to speak in sentences by directly converting impulses from his brain to his vocal tract into words that could be recorded as text on a screen.

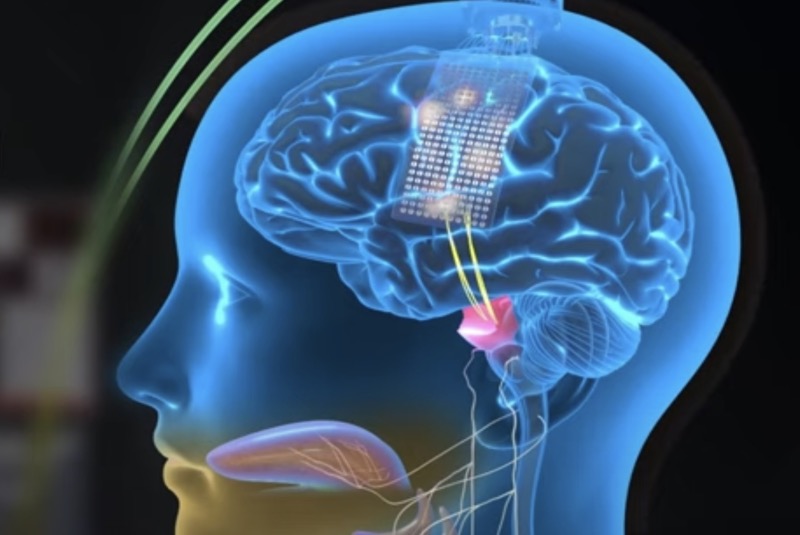

Researchers developed a method for the first time in medical history that harnesses the brainwaves of a paralysed individual to let him speak in sentences. A ‘speech neuroprosthesis’ was devised to allow a paralysed individual to communicate again through sentences on a computer screen. It decodes the brainwaves that usually regulate the vocal tract and the small muscular movements of the lips, mouth, tongue, and larynx that produce each consonant and vowel.

It allowed a person with severe paralysis to speak in sentences by directly translating impulses from his brain to his vocal tract into words that display as text on a screen. While it may take years of additional research, this study is a benchmark in medical history, a step towards restoring natural communication for people who cannot talk due to illness or injury.

People who are unable to talk or write due to paralysis have minimal communication options. The subject in the experiment, who was not named, uses a pointer connected to a baseball cap to move his head to touch words or characters on a screen.

People who have lost their capacity to speak and are paralysed now depend on gadgets that utilise eye or head motions to spell words one letter at a time. Some people utilise a gadget that lets them control a computer cursor with their thoughts. These technologies, however, are a painfully sluggish and restricted substitute for speech.

Trials with mind-controlled prostheses have enabled affected individuals to shake hands or sip from a robotic arm—they envision moving, and those brain impulses are transmitted to the mechanical limb through a computer.

The recent research, conducted over 48 sessions, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study, headed by Edward Chang—a neurosurgeon at the University of California, San Francisco—created a system that allowed individuals with paralysis to communicate even if they could not talk on their own.

Chang’s team had been tracking the brain activity contributing to speech for years. Earlier, researchers temporarily implanted electrodes in the brains of volunteers having epilepsy surgery to correlate brain activity to spoken words. Much later, they tried to allow someone to communicate via speech.

Chang’s team identified the person as BRAVO 1, referring to his position as the first patient in the research called BRAVO, or Brain-Computer Interface Restoration of Arm and Voice. BRAVO1, in his late thirties, was paralysed and unable to communicate due to a stroke fifteen years ago.

‘The stroke left him nearly completely paralysed in his arms and legs but also in the muscles of his vocal tract,’ said Chang. However, the regions of the brain that produce speech instructions are still functional.

The researchers deciphered phrases from the participant’s brain activity in real-time at a median pace of 15.2 words per minute, with a 25.6 per cent word mistake rate. Chang sees a lot of room for improvement as the normal speech rate is 120-150 words per minute.

In a posthoc analysis, the researchers identified 98 per cent of the participants’ efforts to create specific words. The researchers identified words with 47.1 per cent accuracy using constant brain signals throughout the 81-week trial.

According to news reports, the participant collaborated with the researchers to develop a 50-word lexicon that Chang’s team could identify from brain activity using sophisticated computer algorithms. The researchers implanted the electrode array over the region regulating speech.

The vocabulary comprised terms like ‘water,’ ‘family,’ and ‘excellent,’ was sufficient to generate more than 1,000 sentences about the participant’s everyday life. The team began by presenting the individual with brief phrases from the 50 vocabulary items and asking him to repeat them multiple times.

The crew then asked him, ‘How are you today?’ or ‘Would you want some water?’ The participant’s responses, such as ‘I am quite good’ and ‘No, I am not thirsty,’ showed on the screen.

How did they know the gadget correctly translated the volunteer’s words? They began by making him utter precise phrases like “Please bring my spectacles” rather than answering open-ended inquiries until the computer translated correctly most of the time.

According to lead author David Moses, an engineer in Chang’s team, it takes approximately three to four seconds for the word to show on the screen after the guy attempts to speak it. The communication speed and vocabulary limit are slower than the natural speech. Still, the experiment proved that it is possible to allow people who have lost their ability to speak to communicate again.

‘I think there’s a huge runway to make this better over time,’ said Chang. ‘Most of us take for granted how easily we communicate through speech… It’s exciting to think we’re at the very beginning of a new chapter, a new field.’

The study was described as a ‘pioneering demonstration’ by Harvard neurologists Leigh Hochberg and Sydney Cash. They recommended modifications but stated that if the technology works, it may benefit individuals with accidents, strokes, or diseases like Lou Gehrig’s disease, in which the brain prepares signals for transmission, but those messages get stuck.

According to the research team, the study will now be expanded to include additional individuals with paralysis and communication impairments. They will also enhance the number of possible terms in the lexicon.

It has also drawn attention to the fact that gadgets connected directly to the brain may make it difficult for individuals to distinguish between private thoughts and those they want to make public.

‘We want to make sure the devices we create allow that separation, allow people to be able to think their private thoughts without anything just being broadcast to the world,’ says Chethan Pandarinath, an assistant professor at Emory University and Georgia Tech’s Department of Biomedical Engineering.

He believes it will be simpler with gadgets that depend on brain impulses to control muscles since these signals are usually not transmitted until a person makes a deliberate effort to move.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]