At 11:55 p.m., on 22 December 1964, a passenger train carrying 200 people embarked on its last journey from Pamban to Dhanushkodi. The entire train was found submerged in the water as it entered Dhanushkodi. There was no sign of the railway station. No passengers made it alive.

On 15 December 1964, an area of low pressure over the Andaman Sea was identified. It began to develop after interacting with a tropical wave and became a depression on December 18. Over the next several days, the storm intensified at an increasing rate, reaching hurricane-force winds. On December 23, an estimated 7.6 m (25 ft) storm surge hit Dhanuskodi, a town on the southeastern border of Tamil Nadu’s Pamban Island.

The Rameswaram cyclone, also known as the Dhanushkodi cyclone of 1964, was widely considered one of the most severe storms to have hit India. Dhanushkodi is just 20 km from Rameswaram, a renowned Hindu pilgrimage site and home to the Ramanathaswamy Temple. At the time, it was bustling with pilgrims, tourists, fishermen, and others. It had a police station, church, railway station, school, and over six hundred homes.

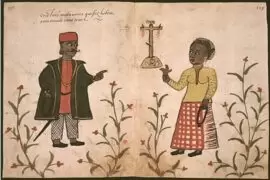

During the colonial era, Dhanushkodi flourished as a port of trade. Just 33 km from the Sri Lankan border, it was a major point of connection between India and Ceylon. Numerous ferry services were operated between Dhanushkodi and Talaimannar in Ceylon. Travellers and traders both utilised the port.

The town was home to many fishermen who depended on the moods of the two water bodies that surrounded Dhanushkodi: the Bay of Bengal on one side and the Indian Ocean on the other. In summer, they fished on the side of the Bay of Bengal. Penn Kedal, as they called it, meaning the feminine sea, was attributed to its calm demeanour in comparison to the Indian Ocean. When the seasonal changes made the waters of the Bay of Bengal choppier, the fishermen moved towards the Indian Ocean.

In December 1964, when the cyclone hit Dhanushkodi, everything about this bustling town was left in ruins. It claimed an estimated eighteen hundred people; about three thousand people were said to have been trapped in a small area of the town. Survivors witnessed the heartbreaking sight of hundreds of bodies floating in the sea.

Most homes, roads, and places of worship were submerged five metres below the sea. The Government of Madras declared Dhanushkodi ‘unfit for human habitation’, and it became a ghost town. However, to this day, some 400 fishing villagers have returned to the ruins of what used to be their homes.

There is no electricity, pipelines supplying water, medical services, or other amenities. They live with some kitchen utensils and old fishing equipment, fetching water from small wells. They dig these shallow wells with bare hands, searching for sweet water for drinking and cooking. The water is filtered through sea aquifers, and these wells have to be only three to four feet deep; any more digging would sweep in saline water.

They see these barren lands as their only home, using solar panels fixed on thatched roofs to generate electricity. Some survivors of the cyclone have been living on these lands without toilets. People defecate in the sand or behind bushes, fearful of insects, reptiles, or jagged corals washed up on the beach by the sea waves. Due to a lack of sanitation facilities, women of the village sometimes have to bathe by the road in the open.

All the villagers are in the fishing business, which their families have carried on for generations. Women work by the side of men in fishing and selling fish. They use traditional methods, such as palm leaves tied to a net, which prevents fish from escaping when they’re pulled out. They venture to the sea at night and return in the morning, measuring the wind, waves, and stars which guide them.

These people earn very little by the end of the day and often live in fear of floating too far out of the Indian waters. The Sri Lankan Navy has a heavy presence in the waters surrounding Dhanushkodi.

The children of fishermen approach pilgrims who travel to Dhanushkodi to perform final rites for their loved ones to purchase seashells. Around the twisting railroad rails, casuarina trees have sprouted. There has been discussion of restoring the town on several occasions, but little has been done due to the magnitude of the damage. It has been in a state of neglect.

Dhanushkodi is slowly gaining popularity as tourists visit to witness the ruins of the cyclone and the beautiful coastline. However, many villagers receive eviction notices to vacate their homes without any resettlement options as the government plans to develop the town for tourists.

The government discourages individuals from residing in villages. In 2006, Dhanushkodi got the first and only state-established school, but students can only attain education until class 5. The 50 or so children in attendance aim to be engineers, doctors, and politicians. If children wish to study more, they need to travel 20 km to Rameswaram, which is usually unaffordable for village parents.

For Hindus, Dhanushkodi is of religious importance. According to mythology, the Hindu deity Ram marked this location with the end of his bow to create a bridge (setu) to reach Ravana’s Lanka. Hence, it is believed that the Ram Setu bridge originated here. Dhanushkodi’s name originated from this myth, and it translates to “end of the bow.”

The state administration wants to attract more tourists and plans to include the construction of two additional jetties. However, the proposals exclude local fish workers, who have lived in this coastal border area for many years.

Dhanushkodi’s children have a deep connection to the water that may be traced back several generations. However, as the government continues to neglect the community, there is little hope for a brighter future than their parents could have imagined. “We have been abandoned; no one comes and asks about how we live here”, say the villagers.

In December 2004, the sea near Dhanushkodi withdrew 500 metres (1,600 feet) from the beach. It was around the fortieth anniversary of the terrible hurricane, briefly exposing the submerged portion of the town. The wreckage of the Rameswaram-Dhanushkodi passenger train, which was pounded by the December 22 cyclone and tidal waves, is half-buried here.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]