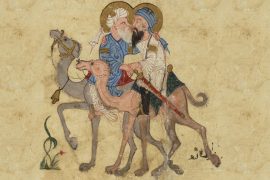

When Abu ‘Abdallah ibn Battuta left his home in Tangier in 1325, he was twenty-one years old, a young man with a scholar’s curiosity and a pilgrim’s devotion. His original purpose was straightforward: to undertake the long journey to Mecca and fulfil the sacred duty of the Hajj. Yet what began as a religious pilgrimage became a lifelong journey.

Over the next twenty-nine years, he would traverse deserts and oceans, empires and kingdoms, travelling more than seventy-five thousand miles—three times the distance Marco Polo claimed to have covered. When he returned home decades later, he had become not only Islam’s most accomplished traveller but also one of history’s most astute observers of the medieval world.

By 1330, Ibn Battuta’s restlessness had brought him eastward to India. The lands of the Delhi Sultanate promised both wealth and opportunity for learned men, particularly those trained in Islamic jurisprudence. At that time, Delhi was ruled by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, a monarch renowned for his intellect as well as his unpredictability.

Ibn Battuta, having heard of the Sultan’s generosity toward foreign scholars, sought a position at his court. Accounts differ slightly on the date of his arrival—some place it in 1330, others in 1332—but his own writings leave no doubt about the grandeur that awaited him.

The Sultan was away when the Moroccan traveller arrived in Delhi, but his reputation preceded him. In keeping with courtly custom, Ibn Battuta presented his gifts, which included camels and horses, arrows, slaves, and other goods gathered along his route.

These offerings, modest by the standards of kingship, were returned many times over. Without even granting him an audience, Muhammad bin Tughluq ordered that Ibn Battuta be lodged comfortably and paid a generous salary of five thousand silver dinars—income drawn from the taxes of two and a half villages.

When the Sultan finally returned in June, he received the newcomer with the effusive warmth that alternated with his fits of cruelty. Holding the traveller’s hand, he declared, “Your arrival is a blessing; be at ease; I shall give you such favours that your fellow-countrymen will hear of it and come to join you.”

For a time, the promise held true. Ibn Battuta was appointed qazi, or judge, an honour that gave him both prestige and proximity to the mercurial ruler. The court life he recorded was one of abundance: gold and silver coins were flung to the cheering crowds, sumptuous banquets were held, and extravagant hunts blurred the line between royal leisure and warfare.

The Sultan was, as Ibn Battuta later wrote, “far too free in shedding blood,” a man who punished “small faults and great, without respect of persons, whether men of learning or piety or noble descent.” Yet he could also be magnificently generous.

When the young judge fell into debt from his indulgent lifestyle, the Sultan not only forgave him but continued to supply him with funds, even acceding to his bold requests for money to repair his house or care for a mausoleum.

It was during this period that Ibn Battuta composed an account of the Qutb complex in Delhi, including the great Qutb Minar—a monument whose height and intricacy left him awestruck. The scholar’s curiosity was as expansive as his travels; he observed architecture, customs, and languages with a precision that would later make his memoir one of the most valuable ethnographic records of the fourteenth century.

But the glitter of Delhi could not conceal its growing instability. In 1335, a terrible famine swept across northern India. It lasted for seven years, leaving the countryside desolate and the people starving. Ibn Battuta described scenes of such desperation that they border on the unbearable: men reduced to eating carrion and human flesh, families driven to madness by hunger. The Sultan was away during much of the crisis, campaigning against rebels. When he returned, the city he had built into an imperial capital seemed to tremble beneath his anger.

Suspicion and fear became the rhythm of court life. When a group of governors and army officers near Delhi rebelled, Muhammad bin Tughluq crushed them with theatrical savagery. Ibn Battuta watched as prisoners were executed in the most grotesque of public spectacles—some torn apart by elephants, others hacked to pieces while music blared from drums and fifes.

For a man trained in the law of Islam, the Sultan’s arbitrary punishments must have seemed like a perversion of justice. Yet, ever pragmatic, Ibn Battuta continued to serve, aware that defiance could mean death.

His personal fortunes soon darkened. He had married a daughter of a court official, a man later implicated in a conspiracy against the Sultan and executed. The connection placed Ibn Battuta under suspicion.

Worse still, he had been friendly with a revered Sufi mystic who defied the Sultan’s command and was punished in a manner that epitomised the ruler’s cruelty: his beard plucked out hair by hair before he was tortured and beheaded. When the Sultan ordered the names of the mystics’ friends, Ibn Battuta’s appeared among them. He was arrested, stripped of his possessions, and exiled to a cave outside Delhi, where he lived in enforced solitude for five months.

Then, as unpredictably as it had begun, his exile ended. The Sultan’s mood changed; Ibn Battuta was summoned back and restored to favour. By now, though, he had learned that survival in Delhi required more than learning or loyalty—it required the wisdom to know when to leave.

Fearing another turn of the Sultan’s temper, he sought permission to resume his travels under the pretext of a religious mission. Fortune, or perhaps the Sultan’s restless ambition, offered him a way out. Muhammad bin Tughluq appointed him ambassador to China, entrusting him with a convoy of ships laden with gifts for the Mongol emperor.

The appointment was both an honour and a peril. As the caravan moved south toward the coast, it was attacked by bandits. Ibn Battuta narrowly escaped with his life while several of his companions were killed or scattered. The mission collapsed, and with it, his last formal tie to the Sultanate.

But the misfortune became another turn in the traveller’s ever-lengthening road. Instead of returning to Delhi, he journeyed through the Deccan and along the Malabar Coast, regions he found rich with trade and cultural diversity.

He marvelled at the cosmopolitan ports of Calicut and Kollam, where Arab merchants, Hindu traders, and Chinese sailors mingled in a web of commerce that spanned the Indian Ocean. The Muslim communities of Kerala impressed him deeply with their learning and prosperity.

He remained three months in Calicut before sailing onward, stopping in the Maldives, which he described with wonder as “one of the marvels of the world.” There, he found another court eager to employ his talents. He briefly served as judge once more before continuing eastward toward Sri Lanka and, eventually, Southeast Asia. His Indian sojourn—spanning nearly a decade—ended as dramatically as it had begun: amid the shifting tempers of kings and the hazards of oceans.

What Ibn Battuta left behind was more than a travelogue; it was a mirror held up to a turbulent era. His writings, dictated years later in Fez to the scholar Ibn Juzayy, remain among the richest primary sources for fourteenth-century India. Through his eyes, we see not only the splendour of Tughluq’s empire but also its decay—the famine that starved its people, the cruelty that hollowed its grandeur.

The Sultan’s ambition had known no limits. He had moved his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in a disastrous experiment that uprooted an entire city. “One of the gravest charges against the Sultan,” Ibn Battuta recorded, “is his forcing of the population of Delhi to evacuate the city.” The image he left of the blind man dragged forty days across the plains, until all that reached Daulatabad was his leg, stands as an emblem of unrestrained tyranny.

Yet Ibn Battuta’s own story resists despair. Where kingdoms fell and rulers vanished, the traveller’s words endured. They traced the fragile thread that connected the courts of Africa, Arabia, India, and China—a world bound together by faith and curiosity long before the age of empires.

In that sense, his time in India was not merely a chapter of peril and survival but a testament to the reach of human wonder. From the palace of the unpredictable Sultan to the ports of the southern seas, Ibn Battuta’s journey turned the map of the medieval world into a single, continuous road—a road that began, as he once wrote, “beneath my feet.”

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]