The story of war is as old as human civilisation itself. In the Greek epic ‘Iliad,’ the Olympian gods, goddesses and minor deities fight among themselves, often using humans to fight other gods. In the ‘Bhagavad Gita,’ Lord Krishna exhorts a reluctant Arjuna to fulfil his duties, and uphold Dharma.

Is it morally justified to kill people, for a cause, however noble?

Pacifism, a word coined by the French intellectual Emile Arnaud, refers to an unconditional rejection of all forms of warfare and violence to obtain political, economic, or social goals. This could be purely on moral grounds, or because of pragmatism, rooted in the belief that the costs of war are so high that alternate ways of dispute-resolution should be explored.

Some well-known examples of pacifism in practice – all based on Ahimsa and non-violent civil disobedience – include the Irishman Daniel O’Connell’s fight for Catholic emancipation, Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership of India’s freedom struggle, Martin Luther King’s movement to put an end to discrimination and unjust laws against the coloured citizens in the United States.

There is a school of thought that considers pacifism as self-contradictory. In an egalitarian society, everyone has rights and responsibilities. The right to fight and prevent infractions of one’s rights is an integral part of it; it may become impossible to accomplish this without force. The delicate balance between rights and responsibilities is not sustainable if one party foregoes this right to protect its rights by whatever means necessary.

The ‘Just War’ theory, an antithesis of pacifism, deals with the rights and wrongs of warfare. It is centred around three main themes.

The first is jus ad bellum which is concerned with the circumstances under which the use of force might be justified for which six criteria are used. First, the decision is taken by a legitimate authority, usually the state. Second, there exists a just cause – defence against an aggressor, for example. Third, the intention is right, i.e. not to proceed beyond the just cause towards acquiring power, territories, or resources. Fourth, the condition of proportionality is maintained, i.e. it does not create more damage than it averts. Fifth, it has strong prospects of success. Sixth, and finally, that there are no other available alternatives.

The second theme, jus in bello, deals with the manner in which the warfare is conducted, i.e. what are the limits to the justified use of force?

Three criteria are used: first, the use of force must be limited by necessity, i.e., proscription of wanton violence and cruelty. Second, proportionality, i.e. the damage inflicted must be proportional to the objective. Third, the force must be directed at legitimate targets, with non-combatant parties spared of the violence – as far as possible.

The third theme is jus post bellum, which is concerned with how the wars may be concluded. This theme has no guidelines and is focussed on the responsibilities of the involved parties in the immediate aftermath of war.

Many of the rules of the ‘Just War’ theory are codified in contemporary international laws like the U. N. Charter, and the Geneva Conventions.

However, the ‘Just War’ theory is not without its contradictions. For instance, it invests power and legitimacy in the state and its representatives, but not on the individual. Since every individual is a legitimate authority, s/he should be able to wage war against others, even her/his state. Robbing the individual of this moral right is an invitation to the state to acquire totalitarian tendencies, especially when it enjoys a majority. It makes it easy for the state to incarcerate a person in the name of sedition; it also means unscrupulous political leaders can manipulate public opinion and risk the lives of soldiers and countrymen for self-serving and immoral purposes.

Further, there is no independent way of establishing the legitimacy of ‘cause,’ which is a complex, multi-layered concept. What is a ‘just cause’ to one may not be so to another. Thus, it may be used to justify terrorism. The circumstances get further complicated when terrorists start using human shields to promote their cause, and states offer political and strategic support to terrorist-outfits to fight proxy wars. Thus the ‘Just War’ theory can be used only subject to certain double standards, in an ad-hoc manner.

The most glaring philosophically inadequate loophole of the ‘Just War’ theory comes from unexpected quarters, namely, Science.

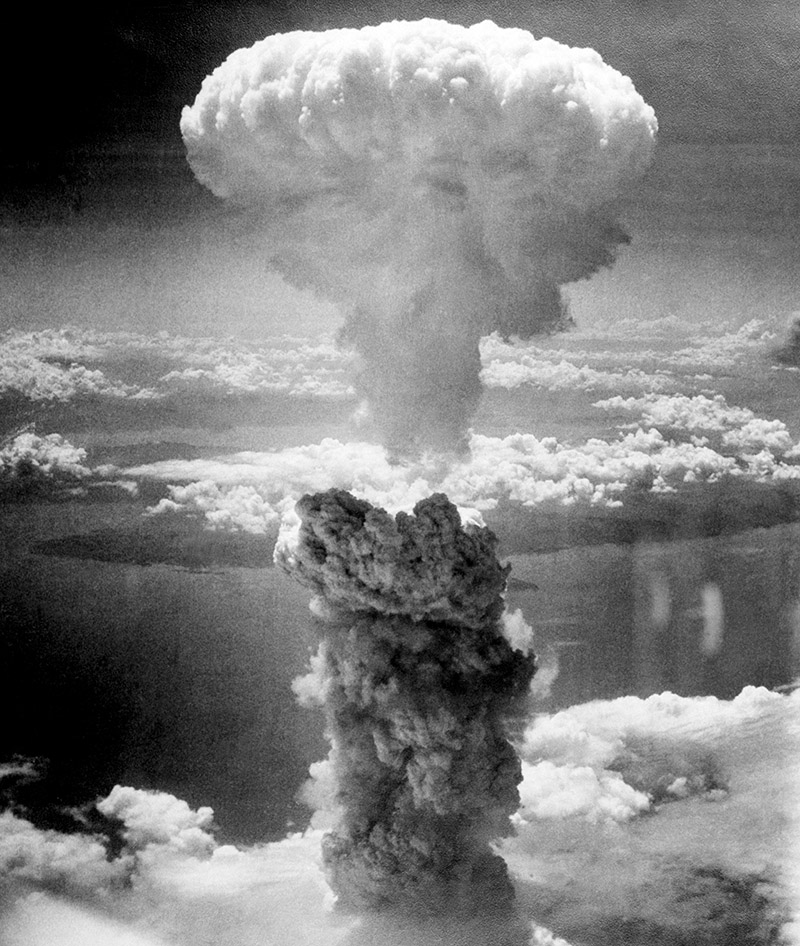

Seventy-four years ago, the ‘Little Boy’ and the ‘Fat Man’ killed over 200,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The ‘Manhattan Project’ that invented these bombs encapsulates the many contradictions of the ‘Just War’ theory. The key scientists in the project, Italian Enrico Fermi and Hungarian Leo Szilard, were immigrants fleeing from fascist regimes.

Others like Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr believed that a bomb in Hitler’s hands would be a great risk to humanity. Einstein and Szilard wrote to the U. S. President Franklin Roosevelt in a letter conveying this fear. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific leader of the Manhattan Project, is believed to have famously quoted from the ‘Bhagavad Gita,’ upon witnessing the first test of the atomic bomb, “I am become Death, the destroyer of the worlds.”

Scientists were equally concerned about the dangers of competition between countries for nuclear superiority once the War ended – fears that were vindicated by the nuclear arms race during the Cold War.

The (Bertrand) Russell-Einstein Manifesto highlighted the dangers of nuclear weapons and called upon world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflicts and gave birth to the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs.

Today, while some commentators speak of the ‘Deterrence Theory,’ it is evident that nuclear weapons in the hands of a suicide bomber, or an accident like Chernobyl, can cause large-scale destruction. Besides, if and when two nuclear powers go to war, there is ever a temptation to launch a first strike to destroy the enemy’s capability.

Even during peacetime, there is always a perception of threat, which leads to a perpetual arms race. The not-so-rich countries caught in this vicious vortex spend millions of dollars on developing and procuring new weapons and technologies, a resource better spent on developmental activities.

Other weapons of mass destruction like chemical and biological weapons, although less-regulated, are equally worrisome. The poignant photo of the ‘Napalm Girl’ from the Vietnam war continues to haunt the civilised world.

Recently, science has veered towards developing artificial intelligence, autonomous weapons, and drones to enhance warfare capabilities; this may minimise collateral damages, and reduce human casualties. Is it possible that since the human costs are less, this could lead to an increasingly hostile world? Where does one draw the ethical line?

Technological developments in satellite communications and the internet, while shrinking the world, have also contributed to the proliferation of virtual wars which are fought with nothing but words. In the words of the influential American thinker and theologian Thomas Merton, “the speech of military strategists and politicians is characterised by a narcissistic finality,…because everything is so organised that you are persuaded not to notice what it is you are talking about. And when that happens, you cannot intelligently converse or argue: all there is is the definitive language imposed by those in power.”

What Merton characterises as “double-talk, tautology, ambiguous cliché, self-righteous and doctrinaire pomposity and pseudoscientific jargon” are weapons of war, most indiscriminately deployed in the information age.

With continued advancements in science and technology, more and more sophisticated and destructive weapons and systems of warfare are bound to be produced to the detriment of the human race. This, in turn, will make the advanced countries increasingly richer, while driving the poorer countries to bankruptcy.

The only hope is to heed the call of pacifism, reinvented to take on the challenges of the times. A saner global leadership should strive to replace the ‘Just War’ theory by a `Just World’ theory where, together, peoples and nations work towards bridging the gap between the haves and have-nots, which is one of the prime reasons for war.

In “Thus Spake Zarathustra,” Nietzsche speaks of an ‘ubermensch,’ an ‘overman,’ who is free from all prejudices and moralities of human society, and who creates his values and purposes. Mankind is just a bridge between animal and overman. The time has come to create a new world order, an ‘ubervelt,’ where the most advanced countries are not the richest, but those that take the lead in putting humanity first, that dismantle their nuclear weapons, and swear by a no-war policy. Terrorists, their state supporters, and states which violate human rights would then constitute a netherworld. The rest of the world can strive to move towards the ubervelt, while continuing to be the bridge between the two worlds.

The time is nigh to reorganise the world around peace and love. We owe it to the posterity.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]