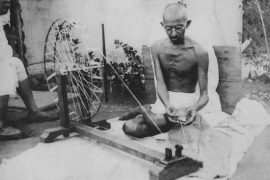

In 1931, one rupee was worth one shilling and six denarius – or 18 pennies. This, was when India was a colony of the United Kingdom. In 2017, India is among the fastest growing economies in the world and the third largest by purchasing power parity. But today, a rupee will buy you barely more than a penny.

The reason is simple: the rupee has been heavily devalued since the British left India to its own devices. But who decides how much the rupee is worth? For many years, the answer to that depended on what the rupee was made of.

The monetary system of Ancient India was influenced to a great extent by Roman coins. Niska, a gold coin, was considered to be the standard currency (though there is a debate whether the Niska was an ornament rather than a currency). As all of the currency could not be made of Gold, Kautilya advocated the theory of Bimetallism. According to this, the lowest unit of currency used the cheapest metal. It allowed for several metallic standards to circulate currency. Kautilya mentioned three standards of currency – the gold Suvarna, the silver Pana and the copper Karsa.

Even in Ancient India, the currency had a global dimension. International markets traded using a Gold Exchange Standard (GES). It necessitated keeping two reserves – one in the country which adopted it and the other at a foreign centre. Thus, an early GES was set with the ‘Māna’. Māna comes from ‘Man’ meaning ‘to measure’. The Māna standard from India travelled to Babylonia and Assyria, where it took the name, Mina. Later, it entered the Greek monetary system under the name Mana.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]