Fascism, it is assumed, has had a peculiar talent for survival. It lingers like a spore, dormant in the corners of societies that imagine themselves inoculated against it, waiting for just the right mixture of grievance, nostalgia, and fear to bloom again. When it does, it often presents itself not as the menace familiar from history books, but as something strangely fragile—a wounded creature rather than an armoured juggernaut. Unlike the triumphant narratives, it is a spectacle of vulnerability that masks deeper, more dangerous impulses. This paradox—the seeming weakness that becomes a source of strength—helps explain why fascism, as both ideology and affect, is able to insinuate itself into the very systems meant to resist it. It thrives not in its moments of triumph but in its posture of persecution.

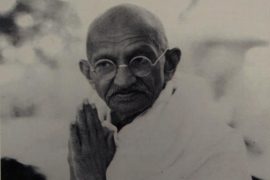

By contrast, the mythology of the communist man has often depended on an entirely different aesthetic of the body. There is a possibly apocryphal story of Stalin enduring a flogging gauntlet so stoically that a blade of grass held between his teeth did not so much as tremble. Whether or not the story is true is beside the point; it expresses an ideal that would later be attached to many revolutionary leaders—a body forged of steel, a will impervious to pain. Psychoanalytic theory might describe this invulnerable communist figure as the embodiment of Lacan’s objet petit a, a remainder that cannot be absorbed or appropriated, the kernel of defiance that gives a movement its symbolic coherence. In Hegelian fashion, this leftover becomes totalised into the physical presence of the leader himself, who stands in for the indestructible idea.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]