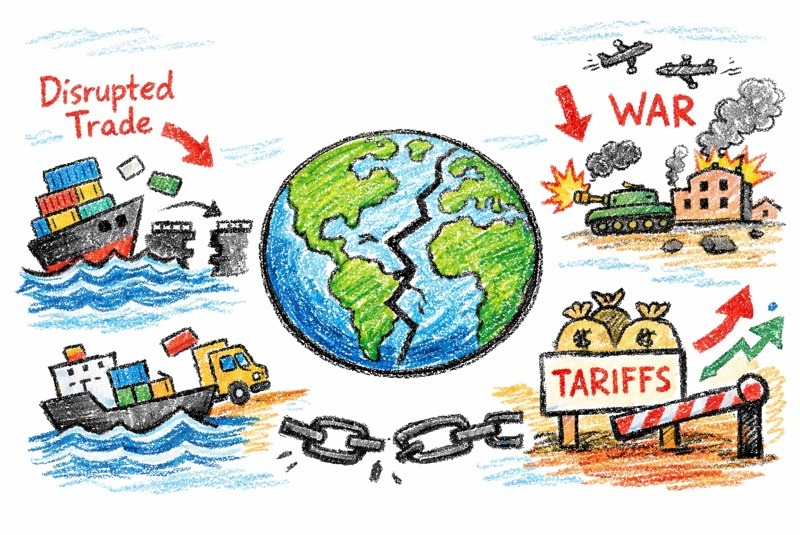

For most of the modern era, the world economy has behaved like a one-way ratchet. It tightens, locks, and refuses to slip backwards. Trade expands, borders soften, technologies shrink distance, and even catastrophic interruptions—revolutions, depressions, world wars—turn out to be pauses rather than reversals.

If you were standing in 1650, watching ships leave European ports with cargoes of wool, spices, silver, and human beings, you could not have imagined a global economy worth more than eighty trillion dollars. Yet that is precisely what emerged.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]