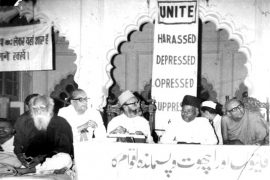

Elections in India have always been a cacophonous, discordant spectacle. Hundreds of millions of voters — who see themselves through regional, religious, and caste identities — exercise their right to vote. It is an exercise unlike any other in the world.

Over the past decade, a subtle shift has occurred in the way Indian elections are conducted. No longer is it just about the grand rallies, the speeches, or the physical presence of candidates on the ground. Increasingly, the battlefield is digital.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]