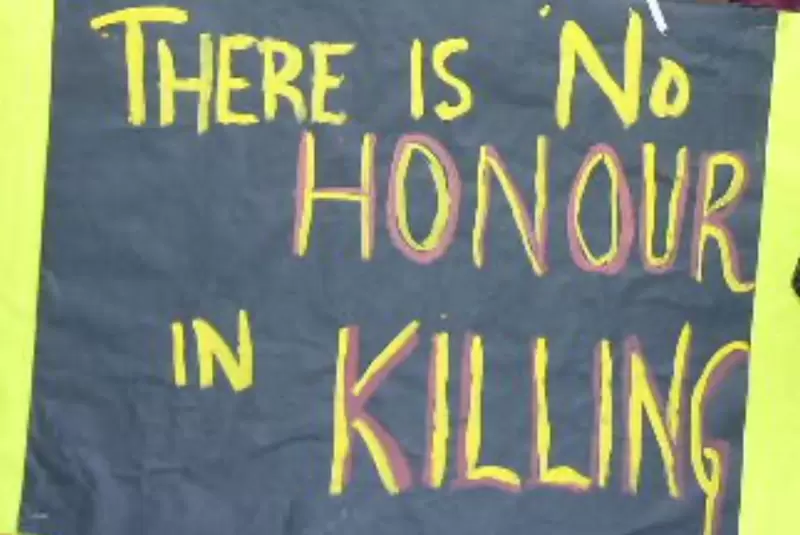

In the heart of modern India, where technological advances and legislative reforms are changing the landscape of society, a haunting practice continues to persist—“honour” killings. These brutal murders, often carried out by the very families and communities that are supposed to protect their members, occur when individuals—primarily young men and women—are killed for violating deeply entrenched social norms.

These violations are often linked to marriage, love, or personal choices, with the central theme being the defence of caste purity, religious honour, or family reputation. Despite the country’s advancements, the shadows of caste and religious orthodoxy continue to dictate the fate of many.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]