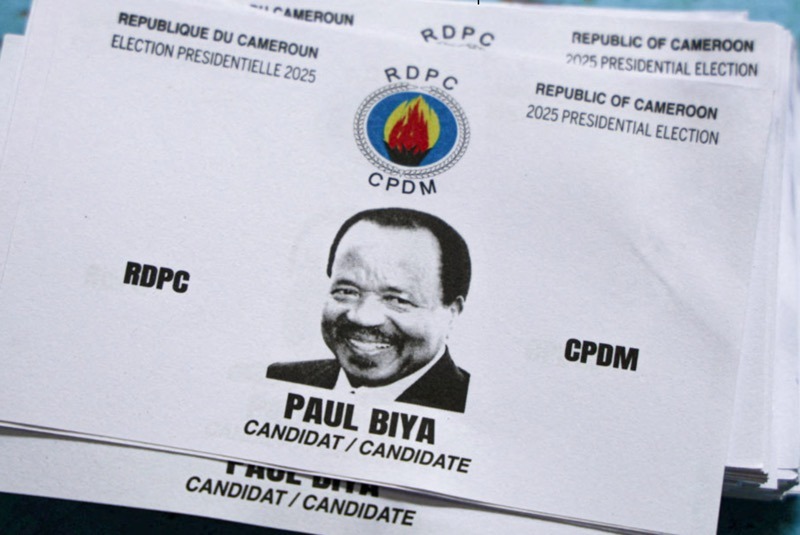

Paul Biya, who has held power in Cameroon for over forty years, is an increasingly anachronistic figure, a ruler who has long outlived any legitimate claim to political vitality. Now 92 years old, he has become not just a symbol of Africa’s lingering autocratic tendencies, but of the extraordinary lengths to which power can be retained through deceit, manipulation, and coercion.

At a time when the political landscape in much of the world is evolving—where younger, more dynamic leaders are coming to power—Biya remains obstinately ensconced in his palace in Yaoundé, resolute in his refusal to relinquish control. His rule, like the frail body of the man himself, seems frozen in time, sustained only by a perverse system of electoral fraud, state-sponsored violence, and a patronage network that binds the country’s elite to his continued dominance.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]