The Greeks dominated most of the ancient thought, science, and mythology. Academics and scholars quote their philosophers even today. The biological findings of Hippocrates are also found accurate in modern times. And mythological beings like Zeus and Hera are not only replicated in Roman mythology but also referred to in popular culture. Some of these gods, like Aphrodite, are even worshipped.

It is no wonder that they also had political influence in other parts of the world. One prominent political figure was Alexander the Great. His ambition to conquer the entire world is well-known. He came to Asia in the fourth century. One of the places he arrived at was India – more specifically, the Indus Valley. Here, he found a peculiar category of people – the Brahmins. He took particular interest in their practices and customs and took some of these Brahmins back with him so that the Greeks and the Romans could learn more about them.

He also tasked the Bishop of Helenopolis, named Palladius, to write an account of the Brahmins. Palladius thus spoke to several travellers and noted down their observations. He combined these to create a booklet called ‘Palladius De Gentibus Indiae et Bragmanibus’ (or Palladius on Races of India the Brahmins).

One of the travellers he spoke to was an unnamed Roman scholar from Thebes, Egypt. He was an elite scholar belonging to the group of Roman lawyers and city officials. He was thus known as Thebes Scholasticus in the book.

His travel story does not start with India since he wasn’t originally planning to go to India. His feet were meant to wander in the valleys and mountains of Sri Lanka, known as Taprobane in Palladius’ book. There is no account of why he wanted to go to Sri Lanka since it wasn’t on the trade map. It was more common to walk past Indian houses and trees. There is also the assumption that he wanted to see if trade was possible between the Greco-Roman Empire and Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was formerly known). How much of this is true? Unfortunately, it cannot be ascertained with accuracy.

Thebes reached Sri Lanka and stayed there. But one day, he met a group of pepper gatherers, or Bisadae, as it is called in the book. These were Indians who arrived in Sri Lanka for trade from Malabar. He heard stories of their land from them and decided to go with them to the land of Malabar.

In a strange turn of events, Thebes was arrested by a local ruler. The scholar didn’t understand the local officials. They didn’t understand him either. The authorities grew suspicious and arrested him. He looked at their gestures and inferred that they mistook him to have committed a grave crime.

Ergo, Thebes was enslaved in Malabar for six years. But in those six years, he learned much more about the place and its neighbouring areas, which housed tribal people. Thebes was released six years after another king had captured the place. In front of the king of Sri Lanka, this king accused the earlier king of wrongfully arresting a Roman. The king of Sri Lanka ordered the previous king to be whipped so hard that his skin came out.

At the time, the kings feared the Roman Empire and worried about the consequences if the Romans found out. For this reason, they released Thebus. This story, however, has a lot of plot holes. It is only assumed that he went to Malabar based on the description of the place. As mentioned in the book, he went to a highland where Indians grew pepper. In ancient times, these highlands belonged to the Malabar region in Kerala.

Other plotholes erupt from the mentions of kings. There is no account of who these kings from Malabar and Taprobane (or Sri Lanka) were. According to the book, the Sri Lankan kings were trading with the Malabar kings, but this is not confirmed. There is also the off-handed mention of tribals in the region. Who were the tribals, what kind of tribals were they, and what was their occupation? Though he observed the tribals, there is no account of his observations.

Thebus’ account of his experience in Malabar ends with his release. After this, Palladius talks about other travellers and their experiences. However, this book establishes that there was trade between the Romans and the kings of Malabar and that these kings did not want to harm their relations with the Romans.

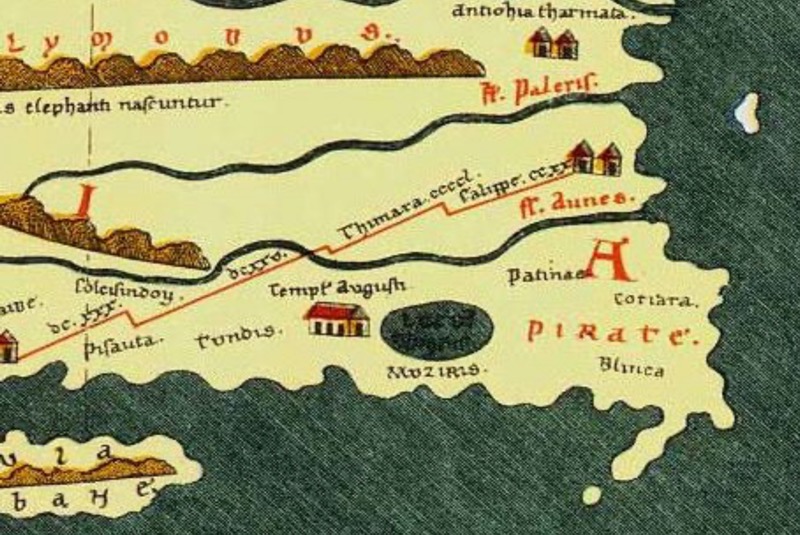

What Thebus did not know (or did not find it necessary to tell Palladius) was that a large port named Muziris on the Malabar coast actively traded with the Romans. It is assumed that Thebus did not know about it because he arrived from a small port in the same region.

Muziris was one of the most prominent and active ports trading with the Romans. Here, they exchanged pepper and other spices for gold. There was even a concrete trade agreement with Alexandria. Evidence of this agreement can be found in the Vienna museum today.

Muziris was established much before the Greco-Roman Empire in 300 BCE. Since its establishment, it has played a prominent role in trade throughout centuries and dynasties. It served as a gate that opened the world to Indian goods. Apart from Rome, Muziris also traded with other countries like China.

Muziris is also recorded in other texts written by the Greeks and Romans. For example, the Roman author Pliny wrote about the place in his book, Natural History, and an anonymous Greek author wrote about it in his book, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

Today, the Muziris Heritage Project protects the remains of what was once a bustling trade centre. The location of the Muziris port is not known anymore. It is a lost port that once put turmeric and pepper in the plates of Greeks and Romans. But Thebus from Palladius De GentibusIndiaeet Bragmanibus did not know about that. Or perhaps he spoke of a place and a time we don’t know about.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]