On October 30, 1884, under the scorching Trinidadian sun, Magistrate Arthur Child and a ten thousand-strong crowd of Indians were at an impasse. What followed was a legacy of resilience and defiance clothed in the garb of celebration.

After the abolition of slavery in 1834, the massive sugar plantations of Trinidad and Tobago ran out of cheap labour required to keep the cogs turning. The owners looked to India. Soon, throngs of ‘indentured’ Indian labourers from Calcutta and Lahore disembarked on the Caribbean shores.

The labourers bound themselves to long workdays for a meagre sum. Such was the nature of ‘indentured labour.’ But their numbers meant they brought with them their food, clothing, religion and celebrations. That is how Muharram or Hosay reached the Caribbean.

The March of Hosay

The small but vibrant community of Indian Shia Muslims introduced Muharram in the islands of Trinidad and Tobago. Soon, the event got its Caribbean flavour and was renamed Hosay, after Hussein, the figurehead of the celebration.

Hussein (or Prophet Muhammad’s grandson) was assassinated in the battle of Karbala 1340 years ago. To this day, Shia Muslims honour his martyrdom, and the tenth day of Muharram is marked by an enactment of the fateful battle.

Hosay was first celebrated on the Phillippine Estate in 1850 and quickly became a quasi-religious community holiday in the Naparimas of Southern Trinidad. The nineteenth-century Trinidad newspapers called it the ‘Coolie Carnival,’ as ‘coolies’ made the cardboard Taziya or Tadjahs. Each estate had its own Tadjah. These lavishly decorated models of mosques were carried through the streets of San Fernando to the beat of the drums and chants of ‘Hossein’ and ‘Hasan’ before being tossed into the sea at sunset.

The Muharram Massacre

The 1800s were a tumultuous time in Trinidad, and the growing numbers of Indians made the authorities nervous. It is recorded that, by 1870, a fourth of the population was Indo-Trinidadian. In 1881, a riot erupted at the Estate of Cedar Hill, and an overseer was assaulted before the police could intervene. A year ago, the restriction on the use of torches resulted in a violent reaction from the African community celebrating Canboulay. Coupled with the depression in the sugar industry in 1884, the environment was ripe for an uprising.

Gauging the situation, on October 26, 1884, Administrator John Bushe consulted the Executive Council on the final arrangements needed to preserve order during the Hosay. The government, through Inspector Commandant of Police, Captian Arthur Wybrow Baker, issued an amendment to the Indian Festivals Ordinance of 1882 that would stop the processions from entering San Fernando.

They planned to divert it so that the tadjahs may be thrown near the King’s Wharf. The amendment also prohibited sword fights or Hakka. These mock battles formed an integral part of the celebration as they mimicked the battle of Karbala. Understandably, the ordinance was not well received.

The Indians who had laboured on the tadjahs for an entire year protested with a petition led by Hindu Sookhoo, a sirdar of the Phillippine Estate. The petition was turned down.

On the eve of October 30, 1884, police reinforcements were stationed at the Court House on Harris Promenade, and the HMS Dido dropped anchor offshore. The stage was set for another battle.

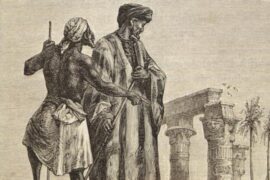

It is said that some Indians did not join the processions. The ones who did planned to march down to the Royal Road through Mon Repos Estate and Cipero Cross. Maybe they hoped the strategically placed police forces would not attack.

At the Cipero Cross, the crowds met Magistrate Arthur Child. The child read the riot act, and the police opened fire. When the smoke and the mayhem cleared, over a hundred lay wounded, and twenty-two lay dead. The tadjahs were left as the carts wheeled the dead to the Paradise Cemetery.

The authorities buried the bodies in a mass grave, upon which now stands the San Fernando Central Market. Many believe the hasty burial meant the actual death toll was much higher.

The British reported the tragedy as the Hosay Riots. The Indians called it the Muharram Massacre.

Today, the Hosay celebrations recall not just the sacrifice of Hussein but those who were slain in 1884. Instead of self-flagellation as is prevalent in other Muslim cultures, Trinidadians take to the streets with songs and dances reminiscent of the country’s iconic carnival. To this day, to the beat of drums, the Tadjahs march to the sea.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]