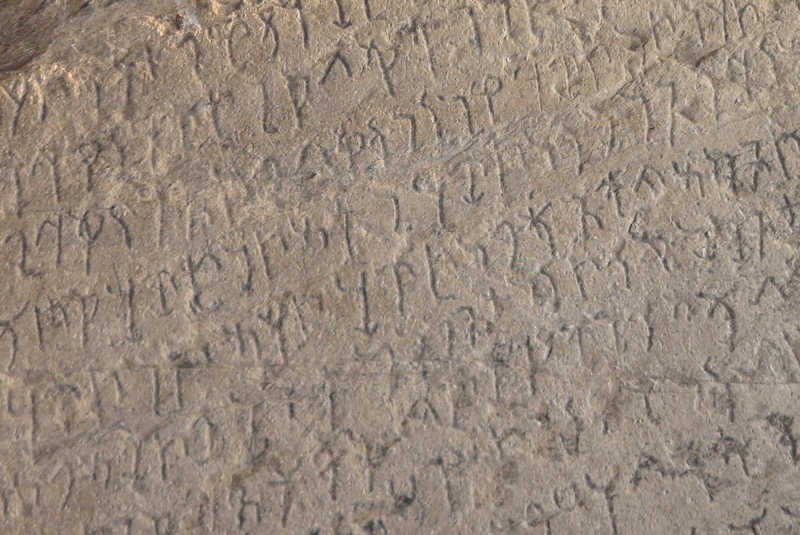

Long before the cartographic lines that now divide South Asia were drawn, before passports, border posts and the anxious vocabulary of partition, there reigned on the subcontinent a king whose afterlife would be longer and stranger than most empires. Ashoka Maurya, who ruled in the third century BCE, sits uneasily in the modern imagination: at once an ancient conqueror and an apostle of restraint, a figure claimed with equal confidence by India’s secular republic and by Buddhist traditions that stretch far beyond it.

In contemporary India, his presence is ceremonial but unmistakable—the national emblem is adapted from the lion capital of the Ashoka pillar at Sarnath, and the wheel at the centre of the tricolour flag is the Ashoka Chakra. Ashoka’s empire once covered territory that now lies in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The physical traces of his rule remind us that history has a way of disregarding the borders we insist upon. It is, therefore, inevitable that some of the most revealing evidence of Ashoka’s moral and political imagination survives in what is now Pakistan.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]