Comics have been – and continue to be – an integral part of media culture. Newspapers and magazines published as early as the 1800s conveyed political satire through cartoons.

Over time, comics steer our imagination through wonderfully illustrated visual stories. However, unfortunately, there is a perception that comics are unworthy of serious, scholarly readership.

Yet, interest in comics – across multiple media platforms – has dramatically increased. Comic books, television series, movies, games, merchandise, and fan fiction catapulted comics into digital meta universes. Now, stories embedded in comics are universes, followed by fans across the world irrespective of age and gender.

But how and why did comics gain immense popularity?

Comics have existed since the end of the 19th century. However, cartoons became popular and expanded into a major industry only after the Great Depression. And during the Second World War, comic book sales increased significantly because they were cheap, portable, and narrated stories of good triumphing over evil. It was during this time that popular characters like Superman (1938) and Batman (1939) were published.

In India, forerunners and prototypes of comic books existed in the form of cartoons and strips, found in Delhi Sketch Book and Awadh Punch, which started publication in 1850 and 1877, respectively.

Indrajal Comics, an offshoot of the Times Group, was the first publication to publish an indigenous comic, Vetal ki Mekhla (The Phantom’s belt). The first thirty-two issues contained stories of Lee Falk’s character, Phantom. After this, Indrajal also published characters such as Falk’s Mandrake and superheroes designed by other American cartoonists, such as Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon.

Translating these comic books into Hindi made them more accessible to a larger audience. The characters had to be altered to fit into the Indian context. For example, Phantom was renamed Vetal to suit the Hindi readership. Captivated by Vetal’s adventures, readers continued buying more and more books, and the series became a commercial success.

Until now, Indian comics were based on characters without Indian roots and were just translations of works of western cartoonists. This changed when the Indian Book House started the Amar Chitra Katha series helmed by Anant Pai in 1967.

While watching a quiz contest on Doordarshan, Pai noticed children could answer questions based on Greek mythology but could not answer who Rama’s mother was. Pai, disturbed by the alienation Indian kids reflected towards Indian mythology, took the onus upon himself to educate children about Indian mythology.

He decided to do that through comic strips because he realised that visual storytelling would impact a child’s mind more than words. To validate his theory, he experimented in a Delhi school to establish that the comic format works well as a mode of communication for young minds. He then conceived the idea of an indigenous comic book for children that would provide information on Indian mythology and history.

India Book House, a publisher based in Bombay, was keen on the idea, and Amar Chitra Katha, meaning immortal picture stories, was born. Although the first ten issues of ACK were Western stories – like Pinocchio and Cinderella – AKC started publishing stories on Indian mythology from the eleventh issue onwards.

In 1969, Pai produced the first issue of Krishna, followed by stories such as Shakuntala and Pandava Princes. In the first three years, ACK sold 20,000 copies. However, by the late 1970s, sales of Amar Chitra Katha comics increased to half a million copies a year.

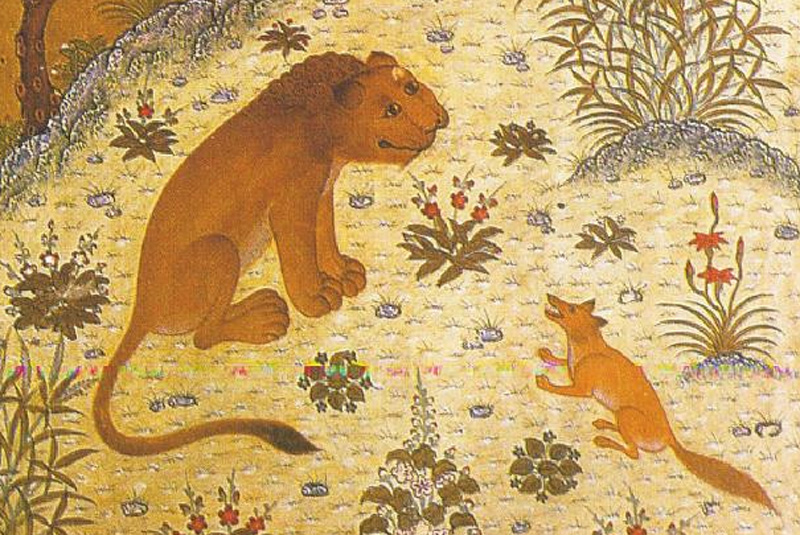

ACK comics mainly focused on puranic heroes and historical characters. Their visual stories – based on different periods of history and iconic figures such as the Gupta Dynasties, Mughals to political visionaries – captured the imagination of millions of people across the sub-continent.

However, these comic strips were criticised for the stereotypical portrayal of women and religious and caste minorities. They were also criticised for creating regional stereotypes. Scholars argued that these comics projected upper-caste Hindu culture as superior and presented the caste hierarchies without criticism.

It also placed an unfair burden of nationalism on its readers through its characters, who were always very patriotic. However, this patriotism was at the cost of the so-called ‘enemies’ who were often religious and caste minorities.

Despite this, the reason for ACK’s success was Pai’s marketing strategy. The core audience was the upper-class urban elite, many of them belonging to a specific socio-economic group. Furthermore, there was an assumption that ancient mythology could not be presented with critical perspectives. So, some comic strips unwittingly glorified the upper caste bourgeoise life and normalised it over time.

It is important to promote awareness about one’s culture and history. However, it is unfair to present stories that stereotype and normalise discrimination. This is important because children who read comics internalised the values shown with a homogenous identity, devoid of diversity, from a very early age.

Though later on, Amar Chitra Katha did try to combat the criticism by publishing stories on Razia Sultana and other eminent personalities.

While many readers might dismiss comic books as sheer banality, the evolution of Indian comics helps us understand how comics are a highly effective pedagogical tool in shaping a child’s mind.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]