The words of the Buddha have taken a long and perilous path to reach the 21st century. Consider any saying you might have heard that is attributed to the ‘Enlightened One’. The Buddha is said to have existed in the fifth century B.C., in a time where none of his teachings were written down. But there exists, nonetheless, a large canon of work based on his exact words.

How did these survive through millennia, in the absence of the written word? The answer is, quite simply, the spoken word. When the Buddha passed away, it’s said that five hundred of his disciples got together and sang. The ‘samgīti’ or ‘singing together’ is called the first council – and it is the root of everything we know (or think we know) about Buddhism.

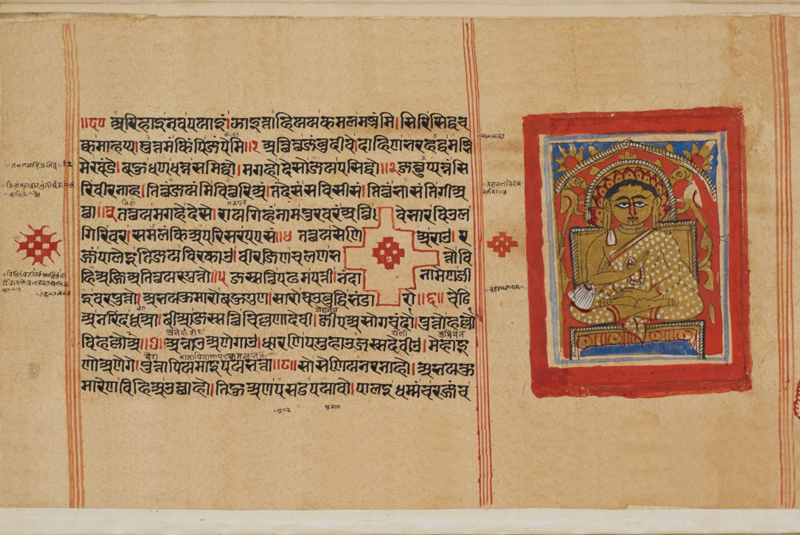

Transmitted generation to generation, sometimes up to 2500 years within a single family, these teachings were in a language that no longer exists today. Or to be more specific, a North-East-Indian language family, known as Prakrit. The Buddha possibly could have spoken Sanskrit – the language of the elites – but he chose a vernacular that was once the lingua franca of the common man.

This became known as Pāli. As Buddhism died out in India, Pāli disappeared from the subcontinent – but was preserved in Sri Lanka and Myanmar. The Theravada school of Buddhism in Sri Lanka lays claim to the only whole set of scriptures that preserve Pāli, although in Burma, the Pali books have been preserved accurately since 387 A.D., through copies made on palm leaf.

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]