In the heart of downtown Srinagar resides Naseer Ahmad Mir, a master artisan whose life is a testament to the enduring legacy of the Kani shawl. At fifty, Naseer embodies the soul of a craftsman. His pale grey skin and meticulously groomed beard reflect a quiet dignity shaped by decades of devotion to his art. Draped in a traditional pheran, clutching a kangri to ward off the winter chill, he moves with the grace of a man who has spent a lifetime perfecting his craft.

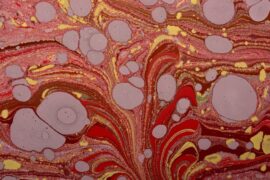

Inside his modest yet meticulously maintained workshop, whitewashed walls and a cemented roof form the canvas for his creativity. His skilled hands dance amidst a kaleidoscope of colours as he deftly manipulates the threads of cerulean blue, emerald green, fiery orange, and regal purple in neat wooden spools, and transforms them into breathtaking patterns. Each thread is a story fragment, and Naseer, the storyteller, weaves these fragments into masterpieces that bear the weight of a centuries-old tradition.

Naseer’s hands, roughened and calloused from years of labour, are a tapestry—etched with the lines of perseverance, resilience, and an unyielding commitment to preserving one of the world’s most intricate crafts. For thirty years, these hands have breathed life into Kani shawls, a craft that earned him a National Award in 2006 from the President of India.

Despite the accolades, Naseer’s life remains simple, and his workshop is a sanctuary where time seems to stand still. Here, the rhythmic click of the loom is accompanied by the soft rustling of threads, creating a symphony that soothes the soul and mirrors the tranquil beauty of Kashmir. Every movement, every decision at the loom, is a step forward that leads to the creation of a shawl that carries within its folds the history and heritage of a people.

The origin of the Kani shawl is deeply intertwined with Kashmir’s history, dating back thousands of years. The craft finds its roots in Kanihama, a picturesque village nestled in the heart of the Kashmir Valley, where the art of shawl weaving has flourished for centuries. Historical texts suggest that the tradition of shawl weaving in the region dates back to 3000 BCE. However, Kani shawls achieved iconic status during the Mughal era,.

According to historians, Kani shawl weaving in Kashmir has Persian roots. During the Mughal era, particularly under the rule of Sultan Zain ul Abideen (Budshah), the valley had more than fifteen thousand functional Kani looms. This historical period marked the most celebrated era for Kani weaving, ultimately paving the way for it to become an art form. As Mohibul Hassan writes in his book Kashmir under the Sultans:

During the sultanate period, other than salt, shawl wool was the most important thing to be imported. From the Mughal accounts, it was known that the shawls were exported to all parts of the world, and there were thousands of shawl factories; however, the exact number cannot be drawn from the chronicles, but it is said that during the era of King Akbar, 2000 shawl factories existed. Most importantly, the taxation system was highly rigid during this period.

The term ‘Kani’ is derived from the Kashmiri word for small wooden spools called tujis, which are central to the weaving process. During the Mughal period, the Kani shawl became a symbol of royalty and graced the wardrobes of emperors and aristocrats. Emperor Akbar was an ardent admirer of these shawls, as documented in the Ain-i-Akbari. Over time, the Kani shawl transcended borders and captivated the hearts of Sikh Maharajas, British elites, and global art connoisseurs.

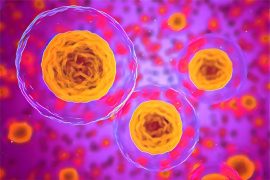

Yet, this illustrious history comes with the weight of responsibility for artisans like Naseer Ahmad, who strive to preserve the craft despite mounting challenges. Creating a Kani shawl is a testament to patience, skill, and dedication. Naseer Ahmad begins each shawl by sourcing the finest Pashmina wool derived from the undercoat of Changthangi goats in Ladakh. This raw material, known for its unparalleled softness and warmth, forms the foundation of the shawl.

The Changthangi goats that reside in the cold desert area of Ladakh grow the undercoat to sustain the region’s winter temperatures (up to -40° C).

Every Kani shawl starts with a design crafted by a naqash (designer). Inspired by Mughal motifs, the naqash sketches elaborate floral and paisley patterns on graph paper. Each pattern is then converted into a talim, a coded script of instructions that guides the weaver through the intricate process. ‘Reading and interpreting the talim is an art in itself, requiring years of practice and expertise.’

Unlike traditional weaving methods that use shuttles, Kani shawls are crafted with tujis. These small wooden spools, loaded with coloured yarn, are manually inserted into the warp threads to create intricate designs. Each step demands precision; even a minor error can disrupt the entire pattern.

Weaving a single Kani shawl is a time-intensive process. Depending on the complexity of the design, Naseer can weave as little as an inch of fabric in a day. ‘A single shawl can take anywhere from six months to over eighteen months to complete. This painstaking effort is what makes each Kani shawl a unique work of art,’ he says.

One of the defining features of Kani shawls is that the patterns are woven directly into the fabric, not embroidered. This seamless integration of design and texture distinguishes Kani shawls from other types of shawls, making them unparalleled in their artistry.

For Naseer Ahmad, weaving Kani shawls has been fraught with challenges. Growing up in a family of weavers, he learned the craft from his father, a master artisan. However, the socio-economic landscape of Kashmir has changed dramatically over the decades, posing significant obstacles to the survival of this heritage craft.

Moreover, weaving a Kani shawl is laborious and time-consuming, yet the financial returns are often meager. And so, the younger generation, lured by more lucrative and stable professions, show little interest in continuing the family tradition.

‘The ancient craft of Kani shawl-making faces extinction within 20 years as young learners, deterred by the patience and dedication required, lack of interest. Additionally, low wages make it difficult for artisans to sustain livelihoods, threatening the future of this traditional art form,’ says Naseer. For Naseer, this trend is deeply worrying. Without new artisans to carry forward the craft, the future of the Kani shawl is at risk.

Efforts are being made to preserve the Kani shawl’s legacy. The shawl has been granted a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, which ensures that only shawls woven in Kanihama using traditional techniques can be marketed as Kani shawls explored to certify their originality.

The Kani Jamewar Pashmina Shawl is the highest mark in craftsmanship compared with any other handloom product. The artistry, labour and time required in creating it make it the most expensive Pashmina shawl available. Kani shawls are preserved and displayed in museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and the Department of Islamic Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Naseer Ahmad is also doing his part to keep the craft alive. He takes on apprentices, teaches them the nuances of weaving and the importance of preserving this heritage. However, he emphasises that greater consumer awareness is crucial. ‘When people understand the time, effort, and history behind these shawls, they are more likely to appreciate and invest in authentic pieces,’ he says.

The Kani shawl is not merely a piece of clothing—it is a symbol of Kashmir’s cultural and artistic heritage. For Naseer Ahmad and countless other artisans, it is a way of life, a connection to their ancestors, and a source of immense pride. ‘The government’s efforts to preserve this art form remain insufficient. While the central government organises workshops and other activities, the state government has yet to take concrete measures to prevent this age-old craft from fading into obscurity,’ he explains.

As we marvel at the intricate patterns and luxurious textures of the Kani shawls, we must also acknowledge the struggles of the weavers who bring these masterpieces to life. Their craft is a bridge between the past and the future, a thread that binds generations. Supporting artisans like Naseer Ahmad is not just about preserving a craft—it is about honouring a legacy, celebrating human creativity, and ensuring that the timeless elegance of Kani shawls continues to grace the world for centuries.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]