In 1842, Dr. Ward Howe, an American philanthropist, visited the home of Florence Nightingale, who was 22 years old at the time. Nightingale was born into an affluent, elite British family. The Howes were the founders of an institution in New York that served visually impaired people. During their visit, Nightingale understood that the world was full of ‘misery and despair.’

Nightingale was convinced that her calling was to volunteer at the hospitals. However, her family disapproved of it because, at the time, nursing was considered to be a ‘lowly profession’ that was ‘not ladylike.’ However, they relented, and finally, in her early 30s, they allowed her to attend the Deaconess Institution in Kaiserswerth, Germany, to pursue nursing courses and then nursing orders in Paris.

Nightingale, often referred to as ‘the Lady With the Lamp,’ is known as the founder of modern nursing. She served in the Crimean War as a nurse, an experience that became foundational to her views on sanitation. Her efforts to improve healthcare significantly impacted the quality of care throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

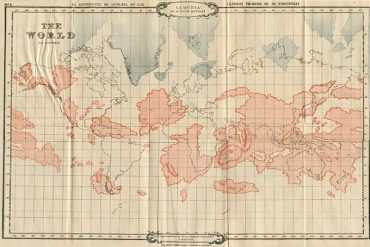

Even though she had never visited India, Nightingale served as an expert on public cleanliness concerns for both the military and citizens. After the Revolt of 1857, which was also known as the Indian Mutiny, there was a call for reforms in the conditions of the British troops in the colonies.

Sickness was responsible for a shockingly high mortality rate among British troops in India. They had to practise for hours in the blazing sun on shadeless barrack squares, had few options for changing their uniforms, and their food was equally inappropriate. In 1859, on average, out of 1000 soldiers, 69 soldiers died every year due to terrible sanitary conditions.

Nightingale was long away from India, but she kept herself updated about the nation, which was a constant topic in her works beginning in 1862, and she was consulted on sanitation issues by authorities travelling to India. According to her, the Crimea crisis was ’a mere trifle’ compared to problems in India.

The British blamed the ‘environment in India’ and miasmic illness, which was thought to be caused by foul-smelling materials, particularly marshes, carried by ‘night mists,’ affecting weak people. However, Nightingale begged to differ. She suspected that the same illnesses that devastated the military camps in Crimea were now at work in India. Sanitation concerns caused by poor drainage, campsite topography, water quality, and housing and hospital buildings, she thought, were primarily responsible. She also hypothesised that the troops’ behavioural variables, such as nutrition, exercise, and alcohol usage, put them at a higher risk of infection.

Despite the distance, Nightingale began an investigation of the health outcomes. Military records and medical statistics were poorly maintained; often, they came with illogical conclusions for the deaths. Nightingale, disappointed with the classification of the diseases, had chided them, asking if “the word witchcraft be assigned as the cause.”

Nightingale convinced the military generals to generate weekly statistics. In case of outbreaks, she requested them to collate statistics on a daily basis. She began organising information and classification of diseases and causes of mortality. Nightingale also asked for wound counts and supported the quarterly publication of the reports for public availability. ‘The main end of statistics should not be to inform the government as to how many men died, but to enable immediate steps to be taken to prevent the extension of disease and mortality,’ she argued.

In a condensed version of the two-volume report of the Second Royal Commission on the Sanitary State of the Army in India, published in 1863, Nightingale concluded that the problem with troops in India was similar to the infectious diseases faced by the wartime camps closer to home. She presented evidence that linked environmental and lifestyle factors to the disease.

Nightingale inspected the water and drainage system and suggested many reforms. Poor drainage system resulted in contaminated water being absorbed by the soil into the shallow wells from which water was fetched for drinking and cooking.

The British troops’ barracks were too crowded, resulting in about 300 men sleeping in little space. Nightingale pointed out that the quarters did not provide enough ventilation. The light and air circulation sources were limited and required to shut close during high winds, dust, and rain. The cow-dung-varnished floors were also unsanitary and affected the health of the troops.

While the reporters often maintained that the soldiers in the troops did not drink too much, Nightingale carefully recorded substance abuse by counting legal proceedings for drunkenness, hospital admissions from alcoholism, crimes from intoxication, and cases of delirium tremens. She argued that while alcoholism would not result in a miasmatic disease, liver problems may arise from it, which in turn will make the health of the soldiers vulnerable to diseases.

Nightingale even examined the diet and quality of life of soldiers. She surveyed the menu, cooking facilities, and amount of food consumed by men and realised that they ate the same food they would eat in British winters during the 48-degree hot summers of India. She strongly recommended changing the diet based on seasons and preparing it in clean kitchens.

The men also spent eighteen hours confined in the barracks, which were overpopulated, with no suitable facilities for recreation. Men spent most of their days eating or sleeping, unlike how a healthy human day would look like. Nightingale campaigned to establish 24×7 libraries, workshops, athletic facilities, community service projects, farmyards, and other activities for soldiers.

In 1874, Nightingale’s 10-year-progress report showed that the annual mortality rate had decreased from 69.5 to 18.69 per 1000 and 16.02 per 1000 lived with disabilities. She argued that the changes saved 51 per 1000 or 2858 men each year, saving 285,000 pounds on recruitment.

Nightingale’s advocacy for soldiers was realised by the development of many recreational facilities for the soldiers. Nightingale believed that the British colonial rule would prioritise sanitisation in India. In her book ‘Life or Death in India,’ published in 1874, she admitted that hygienic conditions had improved, but too slowly. For example, clean water resources were provided throughout the city of Calcutta for all people regardless of their class and caste.

However, with time, Nightingale was genuinely disappointed in the British authorities, not unable but unwilling to bring a change. She was increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of development. By 1888, she had written:

A curious and terrible book might be made of how we have tried to benefit the natives and sunk them deeper than they were before.

-30-

Copyright©Madras Courier, All Rights Reserved. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from madrascourier.com and redistribute by email, post to the web, mobile phone or social media.Please send in your feed back and comments to [email protected]